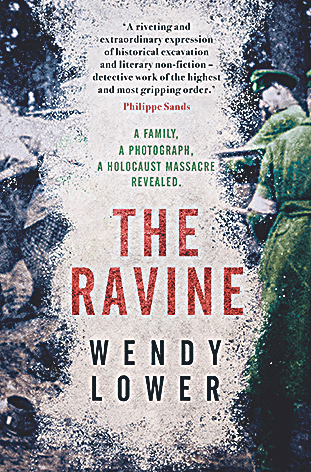

Editor’s note: While this image is graphic and upsetting in nature, we felt that it was important to publish it in full to emphasise its historic importance

This is the horrific moment a Jewish mother and two young children were forced to the edge of a death pit by cold-blooded Nazi executioners holding rifles at point blank range.

Unpalatable, brutal and intrusive – and yet the viewer is compelled to look because such images taken during the Holocaust showing the killers in the act are extremely rare.

Indeed, there are only a dozen or so of such photographs in existence, such were the pains taken by the perpetrators to cover up their crimes.

When Holocaust historian Wendy Lower was approached by two journalists with the photograph, originally taken in 1941 and locked away in the stacks of Prague’s Security Service headquarters for decades, she immediately knew its true value.

Perhaps with a little digging, she could discover when and where this heinous murder – part of a day-long massacre of the Jewish population of a Ukrainian town – took place and, more importantly, track down those responsible.

“For me, it wasn’t even a choice. It was, in a way, a duty and obligation,” says Lower, a former acting director of the Mandel Center for Advanced Holocaust Studies at the US Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington DC.

So began a decade-long investigation in 2009 to uncover everything there was to know about this photograph – where it happened, who was involved, the photographer who took the shot and even the camera with which it was taken.

Lower certainly leaves no stone unturned as she recounts her mission in her fascinating book, The Ravine, published earlier this month.

Through a painstaking reconstruction of events, she was able to discern that the massacre took place on 13 October 1941 – the year that Nazi troops swarmed across Ukraine as part of Operation Barbarossa and orders were given to slaughter the country’s Jewish population – in a forest just outside of Miropol, 135 miles west of Kyiv, in Ukraine.

On the day before the massacre, three SS officers had arrived in the town demanding to know why the town’s Jewish inhabitants were still alive.

They rounded up a group of teenage girls to begin digging a pit in the nearby forest, then called for volunteers to carry out the Aktion, or mass murder, about to take place.

SS officers Erich Kuska and Hans Vogt eagerly put themselves forward, as did Nikolai Ryback and Dmitri Gnyatuk, two Ukrainian customs and border guards who were stationed just outside of Miropol.

In the hours leading up to the massacre, the town’s Jewish community were forced from their homes and herded into the market square, where they were taunted and pelted with bottles and stones by their non-Jewish neighbours.

Then they were marched to the outskirts of a nearby forest and held in a small hut, before being forced out in small groups to make their way to the edge of the death pit.

Bullets, however, were not to be wasted on small children and babies. The youngest of the victims were grabbed by their legs and their heads smashed against the trees.

Neither was there any ounce of humanity reserved for the frail. One elderly woman, unable to walk, was tipped into the pit while still lying in her bed.

In the photograph handed to Lower, a German commander in a pressed jacket and jodhpurs and a Ukrainian soldier in a heavy woollen Red Army coat have just pulled their triggers, the smoke obscuring the face of their female victim in a polka-dot housedress.

She is still clutching the hand of a barefoot boy, while in her lap lies another small child wearing a headscarf.

On the ground next to them lie a pair of men’s leather boots, an empty coat and fired cartridge casings – the discarded evidence of others who lost their lives that day.

Lower pored over hundreds of testimonies and post-war interrogations, spoke to survivors and travelled to Miropol to identify the exact location of the killings.

Remarkably, she also uncovered the life story about the man behind the camera – a Slovakian security guard named Lubomir Skrovina who, having heard the desperate screams of the victims amid the relentless gunfire, instinctively grabbed his Zeiss Ikon Contax camera.

She learnt how Skrovina was not like the perpetrators whom he witnessed, but rather someone who took a series of five photographs in an act of defiance against SS brutality.

Incredibly, Lower even came to hold the very camera that was used by Skrovina that day.

“It was his attempt to show step by step what happened – and it was so deliberate,” remarks Lower. “When I held that camera in my hands, it was as close to that event as I could get. That camera was his tool of resistance, it was what he had available to him to fight against what was happening.

“That was why it was so precious to him and why he specifically donated it to the Bratislava Jewish Community Museum to include in an exhibition on the Holocaust.”

Having discovered so many intricate facts about a single image, there were, however, still details that eluded Lower: the names of the victims. The odds against finding the names were very much stacked against the determined historian.

“Every fourth victim murdered in the Holocaust resided in what is the borders of Ukraine today,” explains Lower.

“Most of them weren’t in the deportation machinery, so we don’t have that paper trail available like we do for other victims.”

Of the nearly 1,000 Jews killed during the massacre at Miropol, Lower found a list of 450. She cross-referenced it with names given to Yad Vashem and among them was a testimony that had been given, alongside a family photograph.

The image showed a group of women from Miropol, including a nurse named Khiva Vaselyuk and two children. One, in a sailor suit, was her nephew, Boris, who bore a striking resemblance to the boy stumbling at the edge of the pit.

The other child was her son, Roman, wearing a head band.

Could they indeed be the victims shown in Lower’s photograph? After speaking to Svetlana Budnitskaya, the surviving relative who gave the testimony, Lower felt that there was certainly a good chance – but the elderly survivor couldn’t be completely sure.

It was a bittersweet conclusion to an investigation that had immersed Lower for a decade.

“In a way it was disappointing and in a way it was a reality check,” she says. “The odds of identifying the victims were already tough, added to the fact that you can’t see the faces and it was difficult for Svetlana. She was only five or six years old in 1941 and had been evacuated with her family, so she had only second-hand information. It was a difficult match. You know it may just be, but we can’t determine that without any questions.”

Equally disheartening was the fact that neither Kuska or Vogt were ever brought to account for their actions, although their Ukrainian collaborators were, 46 years later, when they were both sentenced to death for their crimes.

As Lower says: “Unlike the SS officers, they weren’t trained to kill Jews or deployed in killing actions; they were just regular customs guard checking packages at the local train station.

But they were rabid antisemites and saw this as an opportunity.

“This image is striking in that it shows just how much there is of a shared participation in this act of murder against their Ukrainian-Jewish neighbours.”

After a forensic hunt to find out exactly what happened, Lower hopes to demonstrate how even one photograph can unveil an untold story of the Holocaust.

“No one can assume anything at first glance, and we are reminded that we really don’t know everything that there is to know about the Holocaust,” she adds.

“That sense that we do know everything will lead to erasure, forgetting and suppression – and it will be to our peril.

“We need to remind ourselves the potential is always there to discover more.”

The Ravine: A Family, A Photograph, A Holocaust Massacre Revealed by Wendy Lower is published by Head of Zeus, priced £20 (paperback)