‘After mum’s suicide, the pain and grief felt strangely comforting’

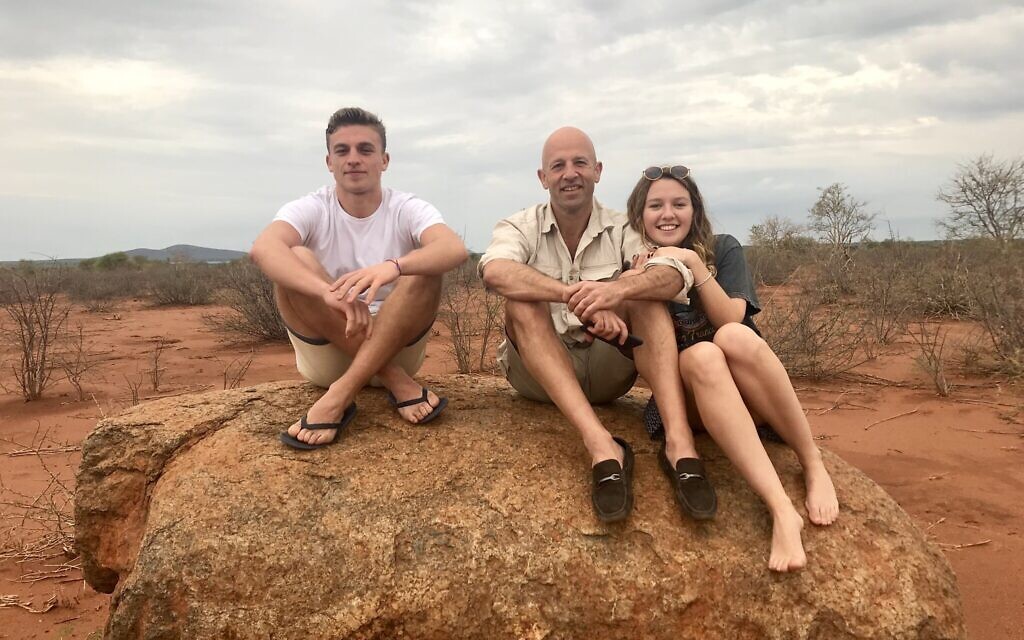

In their first joint interview since the death of Alison Connick in 2014, husband Jeremy and daughter Elizabeth speak about dealing with their loss

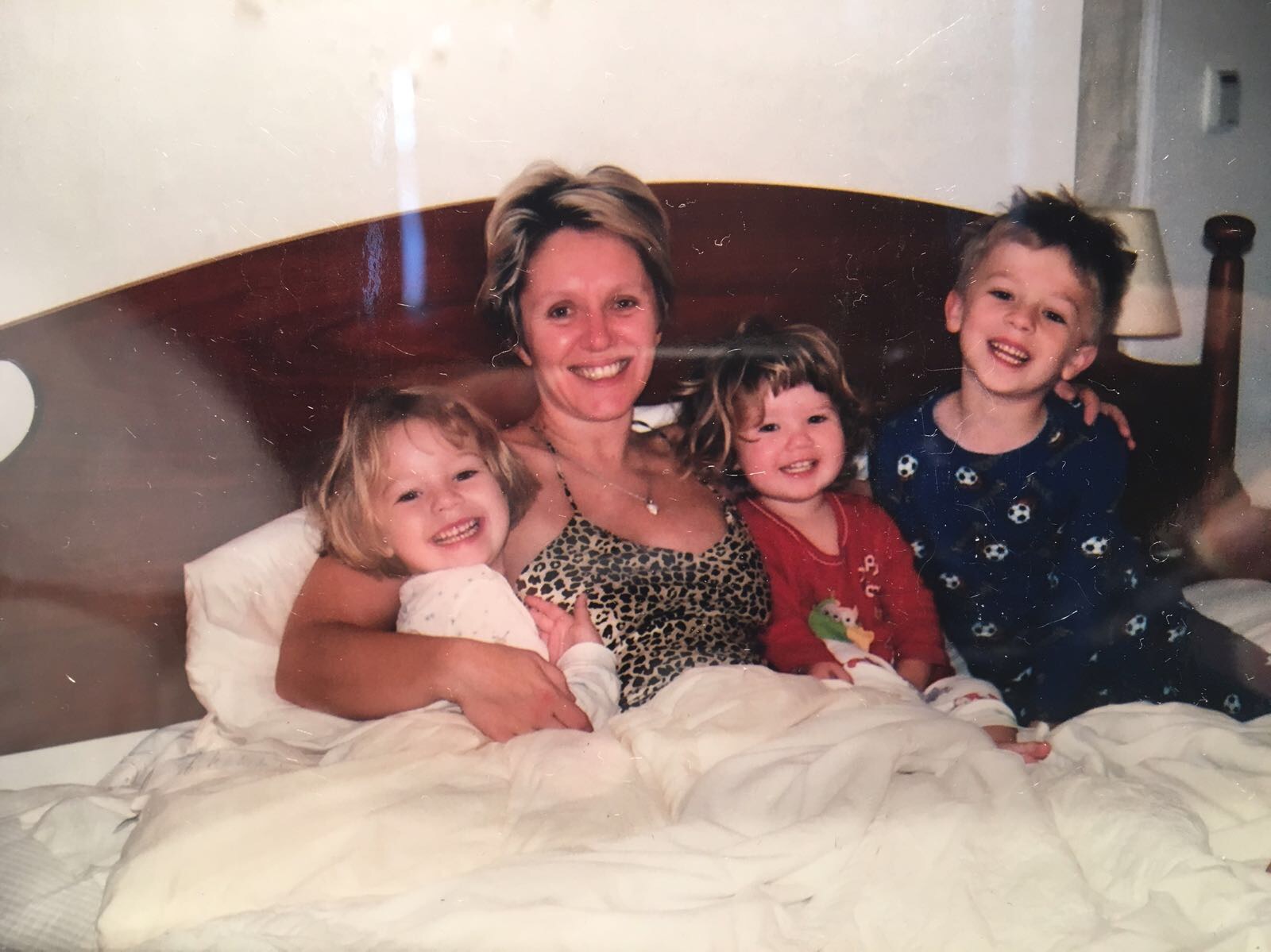

One morning in July 2014 mother-of-three Alison Connick said goodbye to her husband as he left for work, then made her way to Wimbledon train station, entered a restricted section and walked out in front of an onrushing train.

Alison had long struggled with depression and three months before her death had been diagnosed with breast cancer, for which she was undergoing treatment. At the coroners’ inquest her consultant psychiatrist said she had “had thoughts about suicide but no plans,” adding that she had simply suffered “a depressive dip and acted impulsively on the day”.

For mental health awareness week Jewish News (JN) spoke to her husband Jeremy, a solicitor, and one of her two daughters Elisabeth, or Lizzie, who is now 20 and studying at university. It is their first joint interview. Jeremy (JC) has previously spoken about Alison’s suicide in public, in order to raise awareness, whereas Lizzie (EC) is only just starting to.

Get The Jewish News Daily Edition by email and never miss our top stories Free Sign Up

JN: There was a coroners’ inquest, which took several months. Did that help you come to terms with Alison’s death?

JC: It helped me a bit. There were some aspects around her death that I blamed the psychologist and oncologist for, stuff I felt they’d missed, so it gave me the chance to explain how I felt they’d let her down, and therefore us. That made me feel a bit better. My initial thought was to sue them, make a big song and dance out of it, but the inquest calmed me down a bit and realise we just needed to get on with our lives.

JN: Was anger an emotion you both felt?

EC: Definitely. I felt angry a lot of the time, but from about a year after. The first year felt pretty normal in terms of how you should be feeling – I was crying a lot and talking about my feelings. As a family of four we were very close, dad stayed home from work, it felt like we should sit there being sad and we were being but also just getting on with stuff, so I went back to school and Olly went to Uni.

My anger was less at my mum, more at my dad and those still here. In hindsight I was just angry at the situation. I was a 14-year old and everyone at my school had protected, privileged backgrounds, as I did. They hadn’t ever encountered anything that tragic. I think I found reasons to hate my dad, such as when he met Lisa. Looking back he was absolutely entitled to but at the time I was just irrationally angry about it and we had loads of fights.

It felt like we were moving on and nobody was going to remember her, but actually it was about understanding my dad as a person and not someone who had to do what I wanted all the time.

JN: So how did you deal with it? What helped you cope?

JC: We all dealt with it in slightly different ways. For me, I had various attempts at counselling but it was a complete waste of time so I relied on talking to my friends. Negative thoughts – ‘should I have stopped it?’ – they were just going to destroy me, so I guess I practiced some kind of cognitive behavioural therapy, only doing it myself. I told myself that I’d done my imperfect best, that blaming myself wasn’t going to help, and that I was just going to get on with it and look after the kids. It sort of worked, not always, but in general. I was also terrified of the future, I can’t even tell you. It just looked sh*t. All I could see was looking after the kids for 4-5 years then me sitting at home by myself, which was about the most terrifying thing that’s ever happened to me, so when I friend said ‘let the future come to you,’ that helped enormously. It was amazing, because it’s a passive thing, concentrate on today and deal with things when they come to you. That single bit of advice helped me more than anything, that and spending hours and hours talking to friends about Alison. That was my therapy.

EC: I tried therapy a few times. The first time I went I really didn’t want to go. Looking back I had a very teenage view of therapy – ‘I don’t want to talk to anyone’. In a strange way the pain and grief that I felt were quite comforting to me. I don’t know if that’s common. I’ve spoken to one or two people who do understand that. I felt like going to therapy would ‘fix’ me and I didn’t want to be fixed. Maybe I wasn’t ready to be fixed. I went a year or two later, I was 17-18. She was a very maternal figure and I really took to her. The therapy was more around my life, so it didn’t feel like we were tackling this huge issue of my mum. She kind of eased me into it. My sister Zoe had pretty bad trauma afterwards because she was there at the station at the time mum died. Hers was more visual, she had post-traumatic stress disorder, so had specific treatment, but we’ve never actually spoken about it.

JN: How did that second therapist help?

EC: She helped me realise that nothing I could have done would have prevented it. She also helped me understand depression as an illness. Unlike dad, I didn’t have intelligent friends offering good advice around me at that time, and I was finding school hard. Zoe and my brother Olly were both older, with older friends they could talk to. The therapist gave me that. She was also external to the family which was quite nice. She took me through what it meant to have depression, the sorts of things my mum may have been feeling. My biggest problem was on the morning she died I’d woken up, seen her, said ‘hello’ then gone back to bed. For years later I kept thinking about that – I never normally sleep in, I get up early and get on with my day. But that particular day I’d gone back to bed. It really played on my mind for a long, long time. Why did I go back to bed? If I hadn’t done maybe it wouldn’t have happened, that kind of thing. She helped me realise that this self-questioning really isn’t helpful. She helped me to forgive myself.

My sister Zoe had pretty bad trauma afterwards because she was there at the station at the time mum died. Hers was more visual, she had post-traumatic stress disorder, so had specific treatment, but we’ve never actually spoken about it.

JC: Once I’d got over the dangerous thoughts – ‘could I have stopped it,’ ‘should I have stopped it’ – after I dealt with that, I was just sad. I realised that I wasn’t suddenly going to start feeling better after a year, and that that stomach feeling you get when you’ve lost somebody, that represents a relationship, and if you don’t feel it, actually there’s something wrong. So whilst I didn’t celebrate feeling loss, every time I did it reminded me of her and the good stuff we did together. I didn’t feel I needed to be fixed. Yes I get emotional, but I associate that pain with something good, that’s just how I dealt with it.

JN: Sometimes these things can take a while to ‘hit you.’ Did either of you ever have a moment of realisation that Alison wasn’t coming back?

EC: Olly was away at the time of mum’s death. He was coming home on the Wednesday and she’d died on the Monday, so we had to keep it secret, because we wanted to be the ones to tell him. We also wanted to just tell everyone at the same time and get it over with, so dad prepared a message to put on Facebook.

Dad went to get Olly and called from the car to ask me if we’d post it to online. Zoe and I were together laughing and smiling about something, I can’t remember what, but we were pretty happy and felt fine. I remember pressing ‘Post’ – and then I just broke. I remember crying and crying and crying, unbelievable amounts, like I didn’t know possible, just screaming.

It was the first time I thought ‘f***, that’s really painful.’ But I didn’t have just one realisation. I pretended that she was going to come back. I still have that. I’ll be walking down the street and see a woman and think ‘that woman could be my mum, because she has a blonde bob’. It’s obviously completely irrational and in my head I know she’s not coming back, but I don’t think you ever give up that hope, that fake hope, that maybe it wasn’t true. And then you realise again that it is. So you end up having this series of mini-realisations.

…in my head I know she’s not coming back, but I don’t think you ever give up that hope, that fake hope, that maybe it wasn’t true

JC: You kind of know. I went to the police station to identify Alison from a video taken just before she jumped. Walking back it was very clear to me that she’d gone.

Over the next 3-4 years, you still feel like they’re there, because they’ve been part of your life for so long. You turn around and think they’re there. It’s unnerving to say the least. You also have these vivid dreams. One I had, I’m sat in the back of the car with Lizzie, turn to see Alison driving, and say ‘what are you doing driving the car, you dead?’ I still have these dreams. I wake up next to Lisa and think, ‘I shouldn’t be having an affair,’ it takes me a while, then I realise I’m not, it’s OK, but it knocks me sideways for several days, and it’s still happening. I know Alison’s not there, but my subconscious still hasn’t worked it out.

JN: Were people different with you after Alison’s death, or did things they said have a different effect on you?

EC: I began to notice was how often people said ‘I want to kill myself’ when they didn’t like something. They’d even abbreviate it KMS – ‘hate work, want to KMS’. It feels like someone’s punched me in the stomach, but it’s just thrown around, phrases that people don’t understand the full force of. I just think people don’t understand. I had people saying to me, six months after it happened, “why aren’t you over it yet?” It’s either a teenage thing or an ignorant thing.

A lot of the time I felt like I was attention-seeking. Being upset at school, showing my emotion, people thought I was enjoying the attention of it all, which was quite strange because I did want people to help and support me. So on one hand I didn’t want people to think I was seeking attention, but on the other hand I was. ‘Attention-seeking’ doesn’t need to be as negative a phrase as it seems. I was seeking attention because I wanted people to care about me and to understand why I might just start crying in a history lesson.

I was seeking attention because I wanted people to care about me and to understand why I might just start crying in a history lesson.

JC: What was it like when you went to Uni?

EC: They ask ‘what do your parents do?’ I say ‘my dad’s a lawyer’ and leave it there, but sometimes they probe. Generally the reaction is ‘I’m so sorry’ but if they ask how she died and you say ‘suicide,’ then it’s really different. It’s like an extra trauma to the death, but equally they don’t feel like they can ask questions, so there’s this awkward silence, and I can see they feel bad for me, like I must have had this bad family life. It’s becomes less about sympathy and more about confusion, people don’t know how to react, so they just go quiet, and that’s when I feel like I need to justify it – ‘actually everything was fine, it’s just that she was ill’. I can understand it, but I hate it. Because of the discourse around suicide, people think there had to be a reason for her to kill herself.

I remember in Zoe’s year at school there were rumours that someone had cheated. People create stories around the death that don’t exist because it seems more dramatic than dying of cancer, which is why I sometimes just say ‘she died of cancer.’

JC: The brain is a physical thing. When Jonny Benjamin does talks, he gets a model brain out to show you that it’s no different to an arm or any other part of the body that may need repair. Getting that point across is the biggest thing we can do to de-stigmatise suicide.

EC: If everyone saw depression as an illness, everyone would be on the same page, and you wouldn’t get this questioning about whether she had a bad life, or whether she was happy. My mum had the most amazing energy and spirit, just a beautiful person, and I always feel like I need to say that to follow it up.

JC: Alison’s periods of depression were relatively small, and they’d happen in the winter. But talking about how people treat you differently, a lot of people around us used to talk to Alison about depression, because I think a lot of people have some form of depression, maybe not as strong as Alison’s… Most of my friends went above and beyond in the days after Alison’s death. Two flew in from Australia the next day. But some really struggled. I think they saw themselves in Alison and wanted to get as far away from it as possible. So while there were some who I was massively disappointed in, who didn’t turn up to the funeral, in retrospect I don’t think they’re bad people, I just think they couldn’t cope, so I totally forgive them.

If everyone saw depression as an illness, everyone would be on the same page, and you wouldn’t get this questioning about whether she had a bad life, or whether she was happy.

JN: What’s your advice to people who may be going through something similar, but who may be at an earlier stage in the journey?

JC: Take every day as it comes, and don’t worry that you don’t have your future mapped out. If you can imagine: you’re going along, you’ve got this amazing wife who’s the centre not just of your life but the life of your kids, you’ve been looking forward to this long future where you’ve been talking about 60 years together, then suddenly you have no future, you can imagine that’s absolutely terrifying. I’m an optimist, glass half-full, but I’d lost my best friend, my soul mate. I was 50, the idea was that I was going to be retired by now, and in five minutes it’s gone. I’ve got these three amazing kids but I’m sat there thinking ‘what am I going to do?’

JN: Did the kids ever see any of that? Or were you being strong and controlled?

JC: No, not at all. I’m crap at hiding emotion. Everyone knows what my mood is. But actually I thought it was important not to hide it, but what I’ve never described is what I’ve just described there, Lizzie’s never heard that. It wasn’t appropriate for me to lay that on them at that time, and while the phrase ‘be strong for the kids’ isn’t right – you have to show emotion so everyone understands that being emotional is OK – but what’s not appropriate is to have the kids feel they have to look after you, so I definitely didn’t tell them what my concerns were. The first thing I said to Olly was ‘you’re not staying here to look after the three of us, you’re going off to University and you’re going to show us how to create a new life, a life after mum.’ He started off saying ‘I’m deferring.’ But two weeks after she died, we were in the car – and I remember exactly where we were – he turned round and said ‘I can either use this as an excuse, or I can use it to drive me on. And I choose the latter.’ That’s what they’ve all done. That’s what they’ve all done.

Jewish News editor discusses this week’s mental health issue of the newspaper

Thank you for helping to make Jewish News the leading source of news and opinion for the UK Jewish community. Today we're asking for your invaluable help to continue putting our community first in everything we do.

For as little as £5 a month you can help sustain the vital work we do in celebrating and standing up for Jewish life in Britain.

Jewish News holds our community together and keeps us connected. Like a synagogue, it’s where people turn to feel part of something bigger. It also proudly shows the rest of Britain the vibrancy and rich culture of modern Jewish life.

You can make a quick and easy one-off or monthly contribution of £5, £10, £20 or any other sum you’re comfortable with.

100% of your donation will help us continue celebrating our community, in all its dynamic diversity...

Engaging

Being a community platform means so much more than producing a newspaper and website. One of our proudest roles is media partnering with our invaluable charities to amplify the outstanding work they do to help us all.

Celebrating

There’s no shortage of oys in the world but Jewish News takes every opportunity to celebrate the joys too, through projects like Night of Heroes, 40 Under 40 and other compelling countdowns that make the community kvell with pride.

Pioneering

In the first collaboration between media outlets from different faiths, Jewish News worked with British Muslim TV and Church Times to produce a list of young activists leading the way on interfaith understanding.

Campaigning

Royal Mail issued a stamp honouring Holocaust hero Sir Nicholas Winton after a Jewish News campaign attracted more than 100,000 backers. Jewish Newsalso produces special editions of the paper highlighting pressing issues including mental health and Holocaust remembrance.

Easy access

In an age when news is readily accessible, Jewish News provides high-quality content free online and offline, removing any financial barriers to connecting people.

Voice of our community to wider society

The Jewish News team regularly appears on TV, radio and on the pages of the national press to comment on stories about the Jewish community. Easy access to the paper on the streets of London also means Jewish News provides an invaluable window into the community for the country at large.

We hope you agree all this is worth preserving.

-

By Brigit Grant

-

By Laurent Vaughan - Senior Associate (Bishop & Sewell Solicitors)

-

By Laurent Vaughan - Senior Associate (Bishop & Sewell Solicitors)

-

By Laurent Vaughan - Senior Associate (Bishop & Sewell Solicitors)

-

By Laurent Vaughan - Senior Associate (Bishop & Sewell Solicitors)