Exclusive : Golda Meir Movie Diary

The film is out and this is screenwriter Nicholas Martin's diary of the struggles to get the movie made, revelations about the Yom Kippur War and working with Helen Mirren

Jan 9, 2016

Elstree Studios.

Final pick-up day on Florence Foster Jenkins. We wrap in the late afternoon gloom. For three years I’ve given this movie my every waking hour. I’ve thought of nothing else. And that’s the problem.

When I heard Florence sing for the first time it hit me like a lightning bolt. I knew her story would make a great movie. But I’ve not had that feeling in years. Florence has consumed every ounce of me. I am exhausted and out of ideas.

I’ve just made a movie with Meryl Streep and Hugh Grant and you’d think the offers would be pouring in; that I’d be sitting pretty. There is a bit of a buzz around. I have had a few meetings in LA and London and I’ve been sent a few books to adapt. Producers have pitched vague ideas in the hope I can meld them into a coherent story. But no one is offering any cash. What everyone wants is a spec script. Ideally, with a big star attached. That’s how I got Florence going. Here’s a stat to make any screenwriter shudder: if you get a movie made the chances of making a second are less than a third. ‘One and done’ is the rule. I try to rest. But how do you rest when you’re fast running out of cash? And the window of opportunity is closing fast.

Get The Jewish News Daily Edition by email and never miss our top stories Free Sign Up

The Idea!

For some time, I had been getting increasingly irritated by any conversations about Israel.

That slither of land ignites a fury like no other. It causes intelligent people to lose their minds. I know they’re talking nonsense but I’m not sure why – so I buy some books and start to read. It’s not long before the name of Golda Meir appears. Vague childhood memories of Golda on the telly begin to flicker. I remember the craggy face in black and white, those

shoes, the fags; above all a tension. Are my memories of Golda from the Yom Kippur War? I would have been 10 at the time. I think they are.

March 2016 Great Marlborough Street, Soho.

I walk with Michael Kuhn, the producer of Florence Foster Jenkins and a living legend. We have spent virtually every day for the past 18 months, together. He is still annoyed with me because I blow my top on the set and began screaming like a maniac: I can’t remember why

I was so upset.“Just to let you know I’m writing a script about Golda Meir” I tell him. He sighs. “Why are you telling me this?” One of Michael’s favourite expressions is: “From your lips to God’s ear”. I am expecting this next but instead he pauses: “I met her, you know. When I was 17. It must have been in ’67. I was washing dishes on a kibbutz, a huge pile of dishes in the canteen, but then I looked around and there was this little old lady standing beside me holding a tea towel. Afterwards, someone told me it was Golda Meir.” He thinks for a moment: “What’s the story?”

April 2, 2016

Tel Aviv.

On a warm spring afternoon, I sip mint tea with Shaul Rahabi, Golda’s grandson, in a Tel Aviv café. I have found him through vague Facebook connections. I tell Shaul about Florence Foster Jenkins, the movie I wrote about a delusional woman who gave the worst concert of all time at Carnegie Hall, New York. He wonders if I see parallels – Florence and Golda, a woman who escaped the pogroms, founded a nation, raised enough

money to equip an army and led her country to victory in a war. “I do. They both stuck to their guns and fought for their dreams. That’s what movies are about.” You’d think that Israelis would love Golda. She created the social security system, built houses, and forged a peace deal with Egypt that lasts to this day. But they don’t. When the Egyptians and Syrians launched a surprise attack in October 1973 Israel was slow to mobilise

its reserve army. More than 2,000 young Israeli’s were killed and Golda is blamed for every last one of them. Shaul finds this excruciating – he wants his grandmother’s reputation restored. “If you tell the truth about Golda, I will help you with your script”. I agree to this.

“Why is Golda blamed for the surprise?” I wonder. “It’s complicated,” he sighs. “You’d better talk to Hagai”.

July 18, 2016

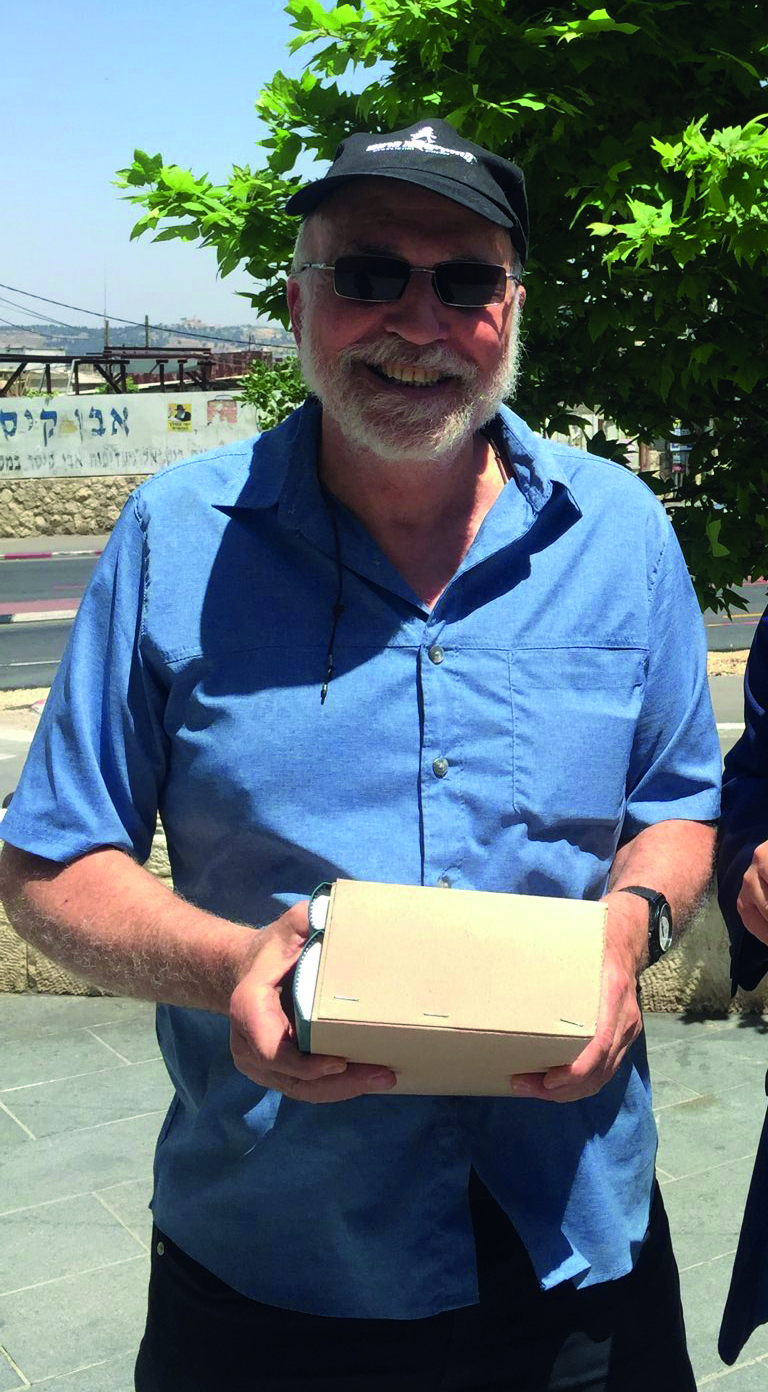

I meet Hagai Tsoref in a café on Balfour Street, Tel Aviv. He’s unassuming, modest an old school kibbutznik. Only later I learn that he’s also one of the two leading historians of the Yom Kippur War in the world and the head of the Israeli national archives. “I hope you don’t mind but I’ve asked Uri Bar-Joseph to come along. He’s written about the war”. Uri arrives.

He has the low centre of gravity of a man who’s seen a lot. He’s the other world authority.

They take it in turns to explain the build-up to the war. How a series of intelligence failures led Israel perilously close to defeat. Every few minutes they break into a heated argument and switch to Hebrew. They assume I know more than I do. I nod along and say “very interesting” a lot but soon I am entirely lost. They keep using the phrase “the special means” – is this code for the nuclear weapon? “The existence of the ‘special means’ has only just

been declassified. That’s why Golda was judged unfairly.”

The ‘Special Means’

That night Uri sends his paper: “The Special Means, the missing link in the Surprise of the Yom Kippur War”. It reads like a thriller. Because Israel had a reserve army it needed warning of any attack to mobilise – 72 hours at a minimum. Military Intelligence had the solution. They placed bugs on the phone lines between the Egyptian front line on the Suez Canal and military HQ in Cairo. When the signal for war was given Israelis would hear it live. The bugs were powered by batteries – and to preserve their life the system would only be switched on during times of tension. And therein lay the catastrophe.

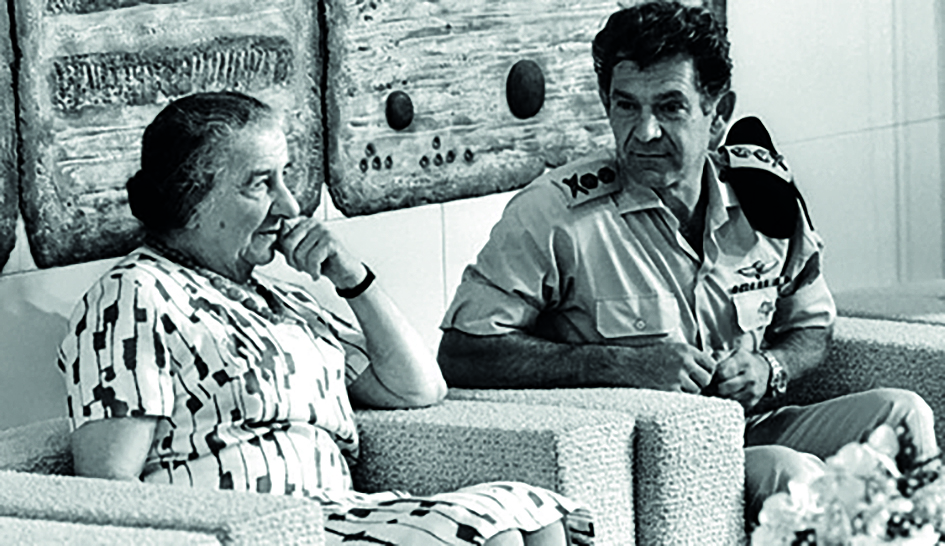

After they crushed the Arabs in the 1967 Six Day War the military leadership did not believe they would dare attack again. Despite the build-up of more than a million soldiers on its borders Eli Zeira, the head of Military Intelligence, chose not to turn the listening system on. When Golda asked him

what he’d heard on the system he replied, “nothing”. Good stuff.

July 20, 2016

A friend has suggested I meet with Eitan Evan, a film producer. We have lunch in a fish restaurant on the dock in Jaffa. He’s smiley and charming but, again, the low centre of gravity. He has his Golda stories. “I did my service in the navy. I was a commando. We had a boat we’d sail from Haifa to Syria or Egypt where we’d swim ashore and carry out attacks.

One day before the war we were checking our equipment when a big car pulled up on the dock. Golda stepped out with a flask of soup and some sandwiches she’d made. She wanted to wish us luck. She stood on the dock and waved as we left.”

Eitan orders fish. I order seafood but he frowns a little. “When the war started there was nothing for my guys to do so we decided to try and rescue some of the kids trapped in the forts on the Suez Canal. We knew the tracks across the marshes near the northern coast of the Sinai so we set off at night in Jeeps. But as we neared the canal we were ambushed by

the Egyptians. We fought all night until we’d killed them all. When the sun came up, we could see bodies everywhere being eaten by crabs. I’ve never eaten seafood since.” I change my order to fish.

Spring 2017

Planning the story

There is just too much information to digest: a hundred biographies of Golda, countless memoirs, histories and documentaries. I create a spreadsheet. Along the top each day and hour, down the side the key locations: Tel Aviv, Damascus, Egypt – and Washington. The latter column grows and I begin to realise the significance of Henry Kissinger in it all. We get hold of Kissinger’s declassified cables and minutes. They paint an extraordinary story. He wanted Israel to win “but with a bloody nose”, as Golda put it.

The journalist Edward Sheehan summed it up thus: “When Kissinger looked at a map of the Middle East, he only saw America and the Soviet Union.” He hoped that by remaining neutral the US would curry favour with the Egyptians and Syrians and they’d abandon the Soviets. Persuading him otherwise took all of Golda’s charm and cunning. Michael Kuhn’s clever assistant Gavin Glendinning prints off the most useful cables, which fill several lever arch files. Michael, a former lawyer, reads them all. We are fascinated. On the day the war starts Kissinger tells the Chinese ambassador that for the US Israel is an “emotional problem”. “Our aim is to drive the Soviets from the Middle East.”

A memo reveals that Kissinger can’t understand why the Israelis were surprised as he was certain they had a spy in at the Egyptian high table. They did. His name was Ashraf Marwan, Nasser’s son in law, but what Kissinger didn’t know was that Eli Zeira, Israel’s head of

Military Intelligence, considered Marwan a double agent and trashed his warnings of war.

April 25th – May 8th 2017

Tel Aviv.

I have a rough story outline but I need more colour and detail. I rent a little room off Allenby Street from Karen, a beautiful American who made Aliyah then trained as a sniper before starting a fashion business. Her fiancé is a veteran of the Gaza wars. He’s more accomplished than me in many ways. When the air-conditioning breaks down, he knows how to fix it. Over the next 10 days I have 30 meetings. I try to track down anyone that was in the command bunker, known as ‘The Pit’ during the war. I meet Uzi Eilam, who headed the IDF’s research department during the war. “Golda would sit there in ‘The Pit’ smoking and drinking coffee. She never moved or spoke. We were all frightened of her – but she gave us hope. She told me that if we captured a SAM 6 missile system, I should tell her so she could trade it for some Phantoms.”

David Ivry agrees to meet. Second in command of the Israeli Air Force (IAF) during the war, he is now head of Boeing, Israel. Though 80, he’s a busy man and can only spare 45 minutes at the crack of dawn. He runs through the story of the war and the dreadful toll it took on the IAF. On his office walls hang photos of young pilots standing by jets. He points out the

dead: “Killed on the Golan … hit by a SAM (surface-to-air missile).” But amongst the photos is an image of smoke pouring from the nuclear power plant in Baghdad after it was destroyed by 14 Israeli jets. Ivry commanded the operation. Finally, he smiles a little:“Publicly the Americans condemned the raid but look at this.” He opens his desk and takes out a private letter of thanks from President Ronald Reagan. “If Saddam had developed a bomb, he’d have used it. Everyone was thrilled.”

I meet with Gideon Meir, Golda’s grandson, an accomplished harpsichordist. We spend the afternoon chatting and drinking. For years after the war, he suffered abuse in public by people who blamed Golda for the carnage of the war. “If Golda had been a man she would not have been treated so badly.” He loved his grandmother dearly and is desperate to

rescue her reputation. We drink more as he pours out information: her love of cooking, her friendship with her assistant Lou Kadar, her habit of drinking tea in ‘the Russian style’, her taste in music.

He has a collection of her clothes and the chunky, inexpensive jewellery she favoured. “I am the greatest living authority on the complex engineering required to support that bosom,” he laughs. Golda was staying with Gideon’s family when the war began. He remembers her returning to their house after three days to change her clothes. She had just seen photos of thousands of graves that Sadat had dug. He was prepared to lose “a million men” to regain the Sinai. It shocked Golda. “The situation is bad, Gidi” she told him, but “sorg nicht”, worry not. As we leave, Gidi offers a final thought: “Helen Mirren should play my grandmother. She’s the only one that can do it.”

Jerusalem.

I meet again with Hagai (Tsoref). He has had access to my spreadsheet and left his corrections in green. I’ve been researching for over a year and the moment comes when I tell Hagai something he doesn’t know: Leah, Golda’s housekeeper loved halva and she put its frosting on all her cakes. He takes it like a man.

More interviews: Avigdor Kahalani, the tank commander who held off a thousand Syrian tanks at the ‘Valley of Tears’ on the Golan Heights; Motti Rachamim, Golda’s Kurdish bodyguard and fearless hostage rescuer; Meron Medzini, Golda’s press secretary during the war and the son of Golda’s friend, Regina. All have details that I’ll work into the script; the

script that at some point I’ll have to start writing.

May 1 2017, Independence Day

Shaul (Rahabi) invites me to the Independence Day service at Kibbutz Revivim. We drive south through the Negev desert for two hours. As we arrive a crowd is gathering at the cemetery. Soldiers fire a salute then the crowd sings Hatikvah, Israel’s plangent national anthem. I am moved. After, we place stones on the graves of Shaul’s parents. He points out

an elderly man who stands nearby: “That’s Topol,” he says. He then shows me the tiny room Golda lived out her last few years.

Shaul’s mother, Sarah, was cut from the same cloth as Golda. In 1943 she and Shaul’s Yemenite father and a group of friends bought a patch of rock and sand from local Bedouin and founded Revivim. It eventually thrived as a plastic moulding plant but it started out as a farm. Shaul’s parents and their fellow kibbutzniks channelled flood water from the local wadi into a pit and lined it with black plastic sheeting. We stand on its rim drinking coffee from a flask. “We built boats and fought pirate battles,” he says. But Shaul was not cut out for kibbutz life and didn’t return after university. For one of Golda’s grandsons to eschew the kibbutz life was a scandal.

We visit a cave in which his mother lived for the first few years, the only place to avoid the heat. British soldiers used it during the war against the Ottomans and it served as a bunker when the Egyptians invaded from across the nearby border. Revivim was cut off and supplied by air drop. Eight of the founders died before the Egyptians were beaten back.

We drive back to Tel Aviv and listen to ‘Song of the Birds’, played by Golda’s friend Pablo Casals. She loved the cello.

I run ideas for the script past Shaul. He nods a few words of encouragement then after a pause says: “Would you like to meet Zvika?” He is referring to Zvi Zamir, the former head of Mossad – the man who warned Golda of war and saved Israel –

the man who witnessed the murder of the athletes at Munich in 1972 then hunted down their killers and eliminated them one by one.

May 3 2017

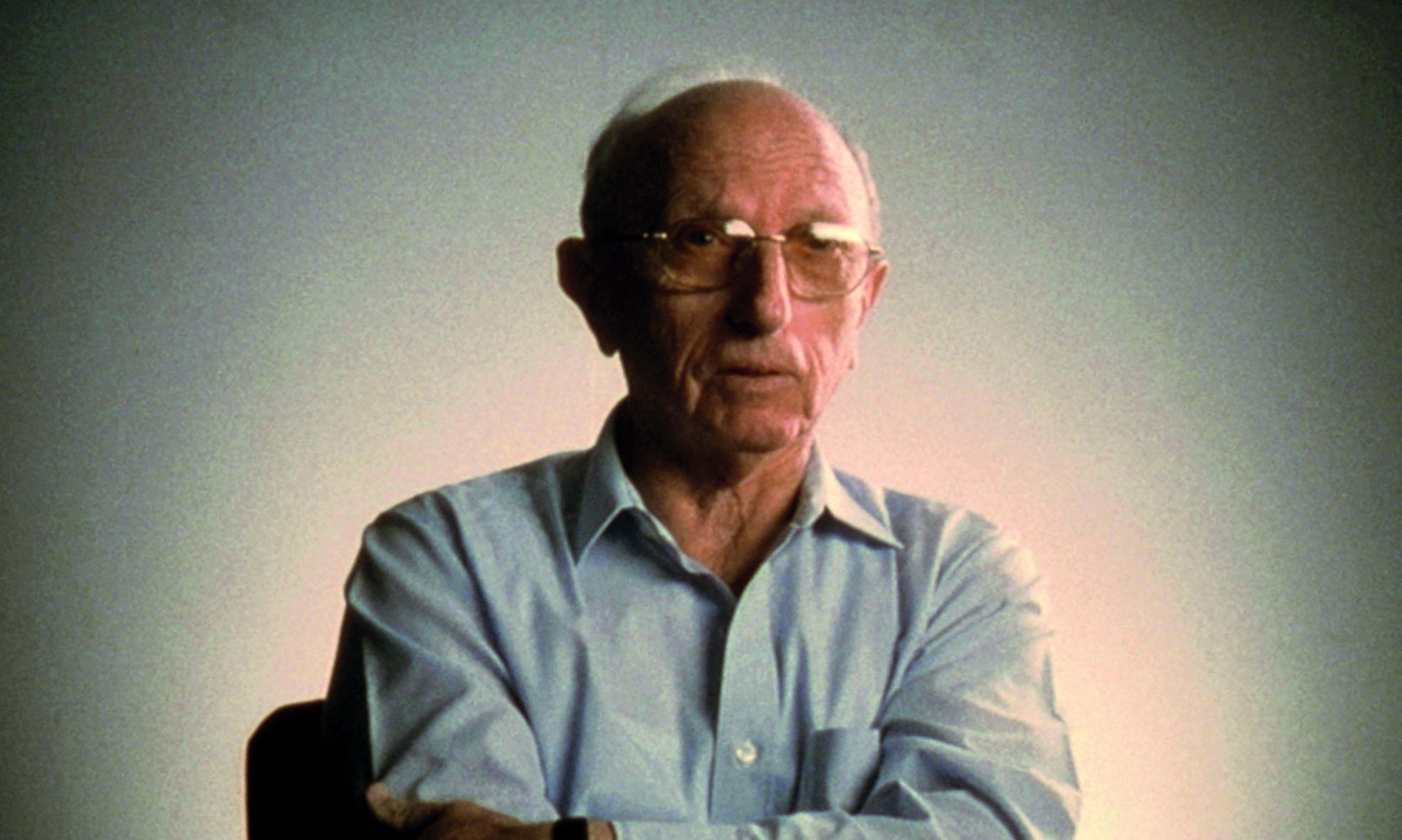

I ring the buzzer outside a modest apartment building in the centre of Tel Aviv. Zamir letsme in and I take the elevator to the fourth floor. He is waiting at the door of his apartment wearing a dressing gown. He’s recovering from shingles. I’ve been instructed not to stay too

long. He shuts the door. “Let us drink a glass of vodka”. It is only 10 in the morning but I think it best to agree.

We sit and drink. He is 93 and painfully slim. His autobiography is entitled Eyes Wide Open. And those eyes, they burn. I ask him about Marwan, the Egyptian spy who tipped him off the day before the invasion. “We rented an expensive apartment in Mayfair. We stocked the bar with fine whisky. We treated him like a prince. Each time we met I would give him

an attaché case filled with money and he’d pretend he was doing it for the cash and I went along with it. But I knew that wasn’t true. He was doing it out of bitterness. He wasn’t taken seriously in Egypt. Working for Mossad was his revenge. I knew I could trust his bitterness. It’s an emotion that can never be satisfied.”

He recalls the shocking moment Marwan broke the news that war was imminent and sending a coded message back to Tel Aviv. He shakes his head. Nearly 50 years later his anger with Eli Zeira, the head of Military Intelligence, still smoulders.“There was no logical explanation for his actions”. I ask him about Golda’s leadership during the war. He thinks then offers a clenched fist: “Golda was strong. Like a rock. That’s all you need to know.”

May 8th, 2017

I am packing to leave when I get a message from Uval Gur, an IDF public relations officer, who is on my side. Avner Shalev has agreed to meet me for lunch. Shalev is the director of Yad Vashem, the Holocaust Remembrance Centre. It’s the first stop for visiting heads of state. Donald Trump is due any day. Pertinently, he served under David

Elazar (Dado), chief of staff of the IDF during the war. Shalev saw it all.

That he’s willing to speak to me speaks volumes about Golda.

We run through the build-up to the war, the schism between Golda’s people and (Mosha) Dyan’s people. Like Zamir he emphasises Golda’s iron determination and cool under pressure. He confirms much of what I know, but then he reveals some gold. “We got a message via the Americans that the Egyptians wanted to meet at Kilometre 101 to talk at

dawn. We drove out there in a jeep and set up a little camp. The Egyptians got lost but eventually turned up in a Russian APC (armoured personnel carrier). It was freezing cold. General Gamasy got out of the APC, but he had no coat and started to shiver. Dado told me to fetch a coat and I gave this old Israeli army overcoat to the Egyptian general and he put it

on. ‘Come with me,’ he said to Dado and they walked into the dunes. I saw him hand a letter to Dado from Sadat.

Dado came over and told me to get Golda on the phone – Sadat was willing to recognise Israel. I fumbled around with an old field telephone and eventually got through to Golda’s office. He breaks into a huge smile and laughs. General Gamasy, the man who’d masterminded the Egyptian attack, was standing there in Israeli uniform sharing a cigarette with Dado when I told Golda the news.”

Winter 2018

I have a first draft of the script. I send it to Michael Kuhn and we meet for a script meeting, which lasts about five minutes. “what’s the story?” is his only note. He’s right. At 125 pages I’ve thrown it all in. I have another go and begin sweating out the fat. In a few weeks it’s down to 105 pages. Kuhn offers no comment but asks what I want to do with it.

Short of money I have sold the script to Ted Hope at Amazon studios. Ted is a delight and a fierce champion of cinema. He loves the script and we discuss the next step. Michael knows Fred Specktor, the veteran CAA (Creative Artists Agency) agent who represents Helen Mirren from his time running Polygram Studios. If Fred recommends the script to Helen,

she’ll read it. The plan works like a dream. Within two weeks Helen has read the script and agreed to play Golda. Ted wants to make a big war movie on a budget of $50m. Then, nothing happens. We sit and wait for a green light from Amazon. It never comes. No studio wants to let go of a Helen Mirren project – they just don’t want to make it.

Jan 2020

Helen meets Guy Nattiv, an Israeli director. She happy with him. Maybe we can get going now?

May 2020

Everything falls apart. Ted leaves Amazon and Golda is stuck. “Now we’re screwed,” sighs Michael, who never wanted to deal with a studio.

But after some tough negotiations, Amazon release the project and we begin hunting around for money. We turn to Hugo Grumbar, a brilliant UK sales agent, and he begins rattling the tin with international distributors. He raises enough money in pre-sales, private investment and bank loan to make the film on a modest budget and $50m is now $13m. I write out the tank battles as we’ll be shooting the whole movie in an abandoned primary

school in Neasden, north-west London.

November 2021

Helen arrives at the ‘studio’ for the first time. She is charming, down to earth and bubbles with energy. “I am so excited,” she keeps repeating and I sense she means it. Karen Hartley Thomas, our make-up artist, begins experimenting and Helen tries on the costumes made by Sinéad Kidao who has lent on Gideon Meir’s knowledge.

A few days later I see the first version of our Golda. Helen sits behind a desk in full make-up and costume. She smokes, fidgets, worries and frowns as she works her way into the role. The effect is mesmerising. Before my eyes a character is emerging. I am overwhelmed with relief. Come what may, Helen’s performance will be world class. There’s very little time to run over the script with Helen: the nip and tuck will have to be done on the day. I’ll not see Helen out of costume for the next six weeks.

December 21, 2021

We wrap at nine in the evening but because of Covid there is no party, no hugs or kisses. I get the bus to Neasden tube station. I arrive home too exhausted to sleep. The shoot has been a colossal strain.

July 12, 2023

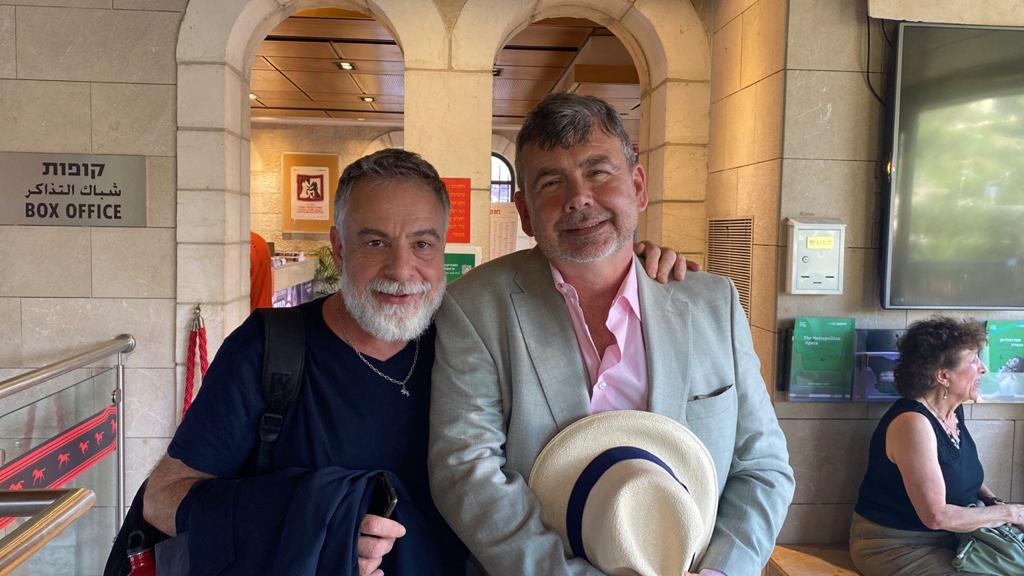

Abu Ghosh, the night before Golda opens the Jerusalem Film Festival.

Over the years I’ve become good friends with Golda’s grandsons: Shaul, Gideon and Daniel. We meet for supper at a restaurant in this Arab town just outside of Jerusalem. Hagai and his wife are there but Uri (Bar-Joseph) has a lecture to give. Though my friend Iris Zaki, the documentary maker, doesn’t know any of them she chats away as though she does. There’s

an openness to Israelis. I make a little speech thanking them all. I wish that Zvi Zamir could be with us but he is now 98 and has succumbed to dementia. We drink toasts to Zvi and to Golda. The film is already causing a rethink of Golda’s reputation.

July 13th 2023 Jerusalem

In the Sultan’s bowl a crowd of 6,000 has gathered for the Israeli premier of Golda. President Herzog takes his seat to angry chants of “democracy!” from the crowd. Iris, an incorrigible lefty, is on her feet screaming like a banshee. But when Helen appears, looking magnificent, all that is forgotten. It’s not often a world class star visits Israel.

She receives a prize and the movie begins. Helen and the president slip away to a dinner hosted by the Belgian Ambassador. I am invited and I’ve seen the movie a dozen times already, but how can I leave? I’ve worked the past seven years for this audience above all others, for all those, both Arabs and Jews, who lost their lives in the Yom Kippur War. For

Golda, the woman who has got me through some terrible times. This is a once in a lifetime moment. So, I stay.

The huge crowd is very silent with a bit of laughter now and again. But as the story reaches its climax Golda tears a strip off Henry Kissinger as she recounts the pogroms that drove her

family from Russia: “I am not that little girl hiding in the cellar,” she spits. Suddenly, the audience erupts in cheers and applause. A shiver runs down my spine. I turn around and see an elderly couple in tears. That is enough.

© Big Hat Stories Ltd 2023. All rights reserved.

Nicholas Martin’s diary is published in September Life Magazine.

Golda is on general release. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=unW5w6JCEb8

Thank you for helping to make Jewish News the leading source of news and opinion for the UK Jewish community. Today we're asking for your invaluable help to continue putting our community first in everything we do.

For as little as £5 a month you can help sustain the vital work we do in celebrating and standing up for Jewish life in Britain.

Jewish News holds our community together and keeps us connected. Like a synagogue, it’s where people turn to feel part of something bigger. It also proudly shows the rest of Britain the vibrancy and rich culture of modern Jewish life.

You can make a quick and easy one-off or monthly contribution of £5, £10, £20 or any other sum you’re comfortable with.

100% of your donation will help us continue celebrating our community, in all its dynamic diversity...

Engaging

Being a community platform means so much more than producing a newspaper and website. One of our proudest roles is media partnering with our invaluable charities to amplify the outstanding work they do to help us all.

Celebrating

There’s no shortage of oys in the world but Jewish News takes every opportunity to celebrate the joys too, through projects like Night of Heroes, 40 Under 40 and other compelling countdowns that make the community kvell with pride.

Pioneering

In the first collaboration between media outlets from different faiths, Jewish News worked with British Muslim TV and Church Times to produce a list of young activists leading the way on interfaith understanding.

Campaigning

Royal Mail issued a stamp honouring Holocaust hero Sir Nicholas Winton after a Jewish News campaign attracted more than 100,000 backers. Jewish Newsalso produces special editions of the paper highlighting pressing issues including mental health and Holocaust remembrance.

Easy access

In an age when news is readily accessible, Jewish News provides high-quality content free online and offline, removing any financial barriers to connecting people.

Voice of our community to wider society

The Jewish News team regularly appears on TV, radio and on the pages of the national press to comment on stories about the Jewish community. Easy access to the paper on the streets of London also means Jewish News provides an invaluable window into the community for the country at large.

We hope you agree all this is worth preserving.

- golda the movie

- Helen Mirren

- Nicholas Martin

- Michael Kuhn

- Florence Foster Jenkins

- Shaul Rahabi

- Hagai Tsoref

- Uri Bar-Joseph

- Eli Zeira

- Eitan Evan

- Moshe Dayan

- golda meir

- Henry Kissinger

- Ashraf Marwan

- Camille Cottin

- Gideon Meir

- Avigdor Kahalani

- Motti Rachamim

- Meron Medzini

- pablo casals

- Liev Schreiber

- Anwar Sadat

-

By Brigit Grant

-

By Laurent Vaughan - Senior Associate (Bishop & Sewell Solicitors)

-

By Laurent Vaughan - Senior Associate (Bishop & Sewell Solicitors)

-

By Laurent Vaughan - Senior Associate (Bishop & Sewell Solicitors)

-

By Laurent Vaughan - Senior Associate (Bishop & Sewell Solicitors)