Exhibition unveils unknown resistance heroes during the Shoah

Fascinating accounts of Jewish resistance in the Holocaust, including by many women, are on display at the Wiener Library

Chazak v’amatz” – “Be strong and courageous” – is a phrase known from the Bible, used by God to encourage Joshua after the death of Moses.

But these were also the last defiant words of 23-year-old Róża Robota, a Polish Jew and leader of four women hanged at Auschwitz for smuggling gunpowder from a munitions factory to the camp’s Sonderkommando, as part of a prisoner revolt that took place on 7 October, 1944.

Robota’s parting call to fellow inmatesis among the fascinating details explored in the Wiener Library’s new exhibition, Jewish Resistance To The Holocaust, which is now open and runs until 30 November.

Get The Jewish News Daily Edition by email and never miss our top stories Free Sign Up

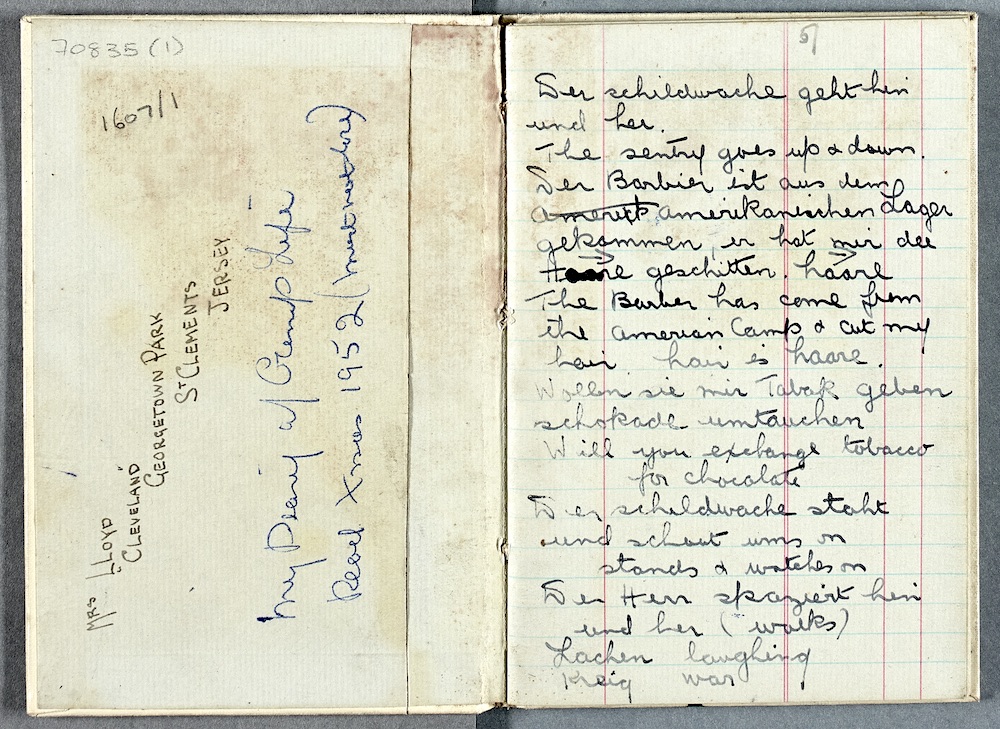

During the 1950s, researcher Eva Reichmann gathered more than 1,000 eyewitness testimonies from resisters in countless ghettos such as Theresienstadt, where people like Philipp Manes kept diaries, and camps such as Treblinka, Sobibor and Auschwitz, where uprisings took place.

Many of these accounts and stories are being shown for the first time in this Covid-secure London exhibition curated by Dr Barbara Warnock.

The library’s director, Dr Toby Simpson, says: “What makes these collections really stand out is their immediacy, whether we’re talking about a quiet act of bravery or a bold act of rebellion, these stories really leap off the page, in part because they were gathered either during the Holocaust or very soon after.”

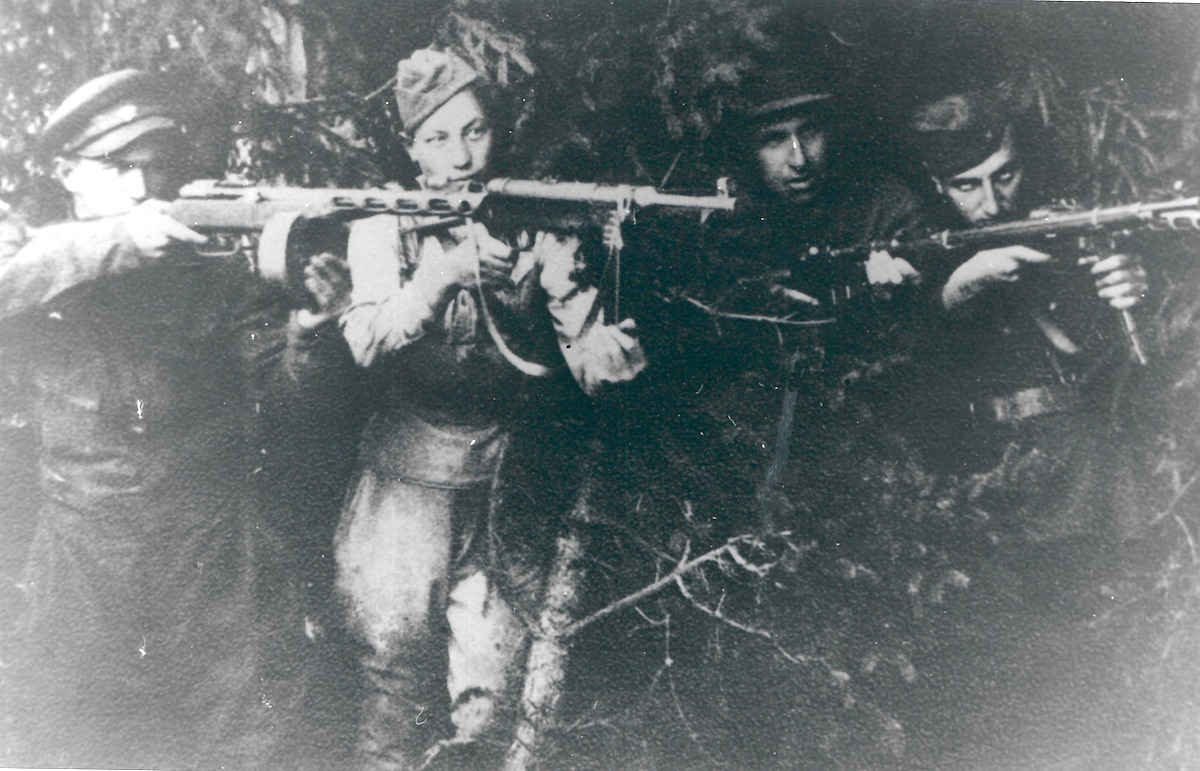

In Britain, we know little about Jewish anti-Nazi resistance during the Holocaust, says Warnock, particularly in the former Soviet Union.

“That was one of the main reasons we wanted to do the exhibition. People just don’t know that Jews were involved in resistance rights across Europe.”

Fighting and sabotage were important elements, but visitors soon learn that armed resistance was far from its only form, because Jewish resistance also included intelligence-gathering and getting evidence out.

Such was the task of Auschwitz detainees Rudi Vrba and Alfred Wetzler, who in 1944 hid for three days in a woodpile near the camp’s perimeter, then escaped when the Nazi search was called off.

They took with them lists of Jews killed by nationality, transport numbers, details of SS officers involved, and a label from a Zyklon B gas canister.

When they reached Slovakia, they told how Jews and others were being gassed on arrival (not “resettled” as the Germans said) and described the camp’s layout and workings. Their report, first lodged in Switzerland, soon made headlines around the world and persuaded Hungarian leader Miklós Horthy to halt the deportations.

Although they resumed some months later, this “pause” saved up to 250,000 Hungarian Jews.

Auschwitz survivor Filip Müller was among the Geheimnisträger (bearers of secrets), disposing of bodies in Sonderkommando, and in 1957 told Reichmann about Jewish resistance within the unit.

Although resistance took different forms, it occurred in every country in Europe. “Even in Ukraine, where it was actually very difficult to resist due to the way the Holocaust unfolded, there were pockets of resistance,” says Warnock.

Individual stories abound: of those who hid in attics, cellars and sewers, and of Norbert Gottlieb, who escaped from a ghetto in Nazi-occupied Poland during mass arrests by hiding in a cavity beneath a pile of potatoes until rescued by the Red Army.

Another comes from Ida Sterno, who worked on child rescue with the Jewish underground. “She concealed Jewish girls in a Catholic orphanage,” Warnock says. “When the nuns heard that the Gestapo were closing in, she worked with the Committee for the Defence of Jews and other local Jewish partisans to stage a fake raid on the orphanage, even tying the nuns up to make it look realistic. It worked. It saved the girls.”

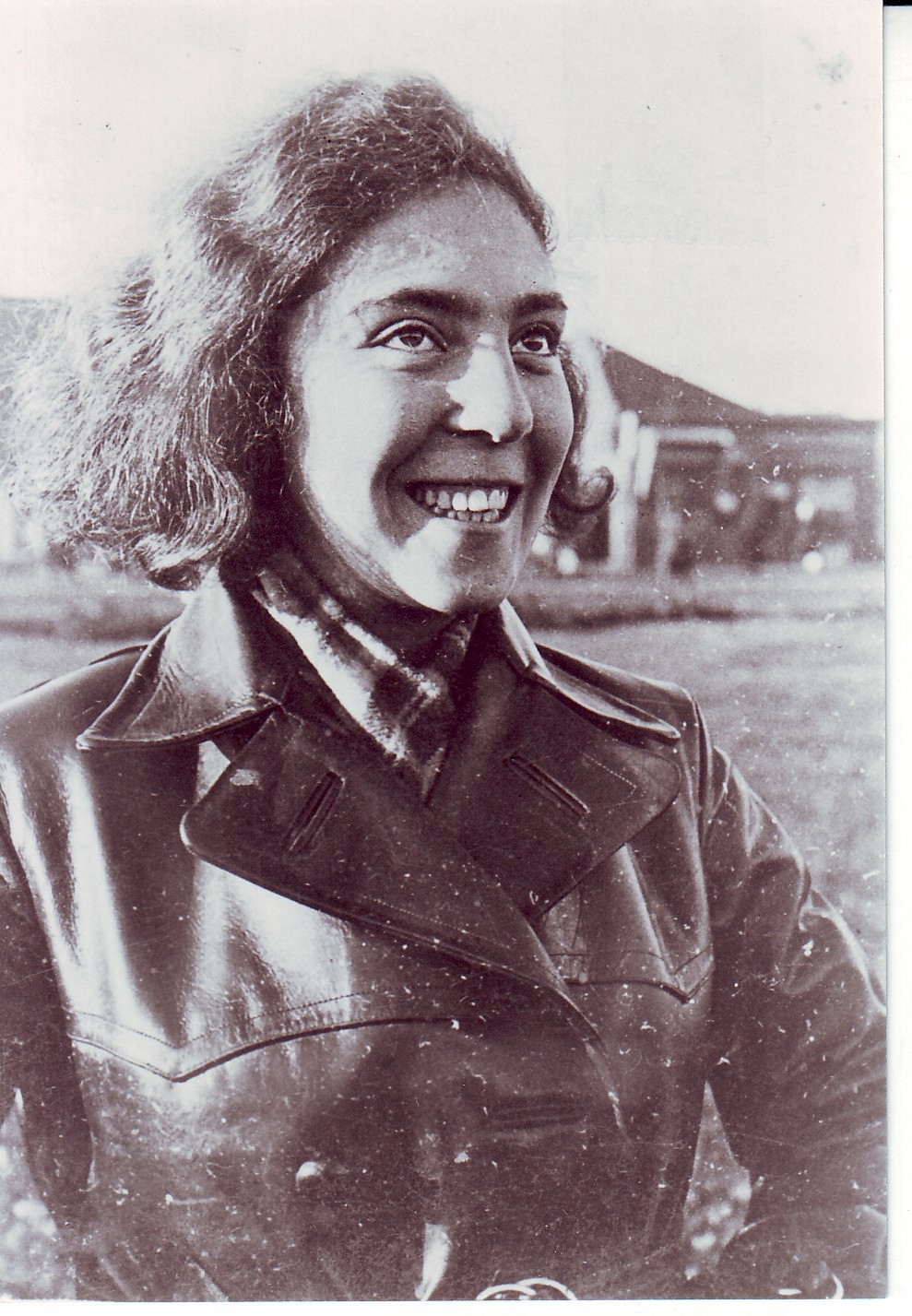

Women feature prominently in this exhibition, including Tosia Altman, a courier for Jewish resistance groups who travelled on false papers to move in and out of ghettos, training people and organising armed revolt.

“The stories of women come up time and time again. They can get overlooked as the more dramatic rebellions, such as the Sonderkommando uprising at Auschwitz, were led by men, but women were essential to them happening – it’s just that they had different roles.”

Jewish resistance around Europe was nothing if not varied, with Zionist groups of left- and right-wing persuasions, anti-Zionist organisation, groups of Jewish Polish army officers, social democratic groups such as the Bund, and communist groups.

They united to great effect in the Warsaw Ghetto, which helped in obtaining weapons, yet in other places they were in conflict, partly because they had different priorities.

In some northern European ghettos, such as in Estonia, Lithuania and Latvia, Jews fully embraced a social, cultural, educational and religious resistance – performing plays, conducting covert religious services and teaching classes in illegal schools.

Yet while scholars such as Prof Samuel Kassow say this spiritual resistance essential to sustaining the armed resistance, it caused problems at the time. In the Vilna ghetto, for instance, armed resisters were furious at this “theatre in the midst of genocide”, famously distributing leaflets titled: “You don’t put plays on in cemeteries.”

The curator’s hope is that people appreciate the “scale and variety” of Jewish anti-Nazi resistance and “the enormous constraints they faced”.

Róża Robota’s call to be “strong and courageous” was exactly what they needed to be – and as this exhibition shows, they so often were.

- Jewish Resistance To The Holocaust is at the Wiener Holocaust Library until 30 November. Open Tuesdays and Thursdays, 11am-3pm. Visitors must book at www.wienerlibrary.co.uk

Thank you for helping to make Jewish News the leading source of news and opinion for the UK Jewish community. Today we're asking for your invaluable help to continue putting our community first in everything we do.

For as little as £5 a month you can help sustain the vital work we do in celebrating and standing up for Jewish life in Britain.

Jewish News holds our community together and keeps us connected. Like a synagogue, it’s where people turn to feel part of something bigger. It also proudly shows the rest of Britain the vibrancy and rich culture of modern Jewish life.

You can make a quick and easy one-off or monthly contribution of £5, £10, £20 or any other sum you’re comfortable with.

100% of your donation will help us continue celebrating our community, in all its dynamic diversity...

Engaging

Being a community platform means so much more than producing a newspaper and website. One of our proudest roles is media partnering with our invaluable charities to amplify the outstanding work they do to help us all.

Celebrating

There’s no shortage of oys in the world but Jewish News takes every opportunity to celebrate the joys too, through projects like Night of Heroes, 40 Under 40 and other compelling countdowns that make the community kvell with pride.

Pioneering

In the first collaboration between media outlets from different faiths, Jewish News worked with British Muslim TV and Church Times to produce a list of young activists leading the way on interfaith understanding.

Campaigning

Royal Mail issued a stamp honouring Holocaust hero Sir Nicholas Winton after a Jewish News campaign attracted more than 100,000 backers. Jewish Newsalso produces special editions of the paper highlighting pressing issues including mental health and Holocaust remembrance.

Easy access

In an age when news is readily accessible, Jewish News provides high-quality content free online and offline, removing any financial barriers to connecting people.

Voice of our community to wider society

The Jewish News team regularly appears on TV, radio and on the pages of the national press to comment on stories about the Jewish community. Easy access to the paper on the streets of London also means Jewish News provides an invaluable window into the community for the country at large.

We hope you agree all this is worth preserving.

-

By Brigit Grant

-

By Laurent Vaughan - Senior Associate (Bishop & Sewell Solicitors)

-

By Laurent Vaughan - Senior Associate (Bishop & Sewell Solicitors)

-

By Laurent Vaughan - Senior Associate (Bishop & Sewell Solicitors)

-

By Laurent Vaughan - Senior Associate (Bishop & Sewell Solicitors)