How ‘Kindertransport 2’ saved thousands of lives

The 85th anniversary of Kitchener Camp this weekend recalls the story of a remarkable wartime rescue project for Europe’s Jews.

November 1938 is infamous in Jewish history. More familiarly known as Kristallnacht, or Night of Breaking Glass, it was tragically more than one night (November 9-11) and involved not just rampaging Nazi destruction of Jewish property in Germany and Austria but also the round-up and arrest of hundreds of Jews who were sent to concentration camps Sachsenhausen, Dachau and Buchenwald.

But the events of November 1938 had an unanticipated result, as Jews in Germany and Britain mobilised to find a way of rescuing the men. In a unique operation, it was the Jewish Lads’ Brigade, known as JLGB, which ran what became known as the Kitchener Camp in Sandwich, Kent.

This weekend, 20 January, marks 85 years since Kitchener opened on the site of a former World War I army barracks. There were four such derelict camps, but in the end only Kitchener was used.

Britain’s Central British Fund (CBF), predecessor of World Jewish Relief, negotiated on several fronts: with the leaders of German Jewry and the Nazi authorities, to get the men out; and with Britain’s Home Office for visas to allow them in.

It was a race against time. The Home Office eventually agreed to the establishment of Kitchener as long as CBF assumed financial responsibility for the men and it did not become a permanent residence.

Almost all the Jewish refugees were allowed in with the object of moving them on as soon as circumstances allowed, but the outbreak of war in September 1939 changed things.

First, however, Kitchener had to be made habitable. By the end of 1938, Britain granted the first of 100 entry visas for Jews who had skills as bricklayers, electricians, carpenters, to come and renovate the camp. Master craftsmen from the ORT school in Berlin were among this first group.

Brothers Jonas and Phineas May ran the camp. Both were in their early 30s, Jonas the former secretary of the Jewish Lads’ Brigade and Phineas working at the United Synagogue. Jonas was named director of Kitchener, Phineas “sports and recreation officer”, although the pair operated as co-directors.

Their appointment was the more remarkable given their only previous experience was running JLB summer camps for teenagers. Kitchener was wholly different, a sanctuary for displaced German Jews arriving in Britain mostly without wives or families, often speaking only basic English.

Kitchener opened in January 1939 and ran until May 1940. Accounts of how many found safety there vary widely. Yad Vashem says 15,000 passed through, while those associated with the camp archives, now housed at the Wiener Holocaust Library, speak of around 4,000, the bed capacity of the renovated facility.

Numbers are difficult to establish because people arrived and left almost continuously. Among those who left, several hundred joined the British Army Pioneer Corps, others emigrated to Australia, Canada and America.

Much of the complex story of the camp has been assembled at the initiative of Dr Clare Weissenberg, who edited the Kitchener Camp Project in tribute to her father, Werner, who arrived in Britain on 6 June 1939.

In 2014, another Clare, Clare Ungerson, wrote a well-received book: Four Thousand Lives: The Rescue of German Jewish Men to Britain in 1939.

Another JLB leader, Ernest Joseph, an architect, was also involved in the rescue by helping to secure the site and directing the men in the necessary tasks to renovate it. This, he said, was “helping men to help themselves,”, but also offered new skill sets to the previously unskilled to help the refugees when they left the camp.

Phineas May’s lively diary, now housed in the Wiener Holocaust Library, together with the camp’s newspaper which he edited, offers a fascinating picture of Kitchener, which featured a hospital, a post office, had its own orchestra and football team and even a 1,000-seat cinema built with money donated by Odeon cinema tycoon Oscar Deutsch. Even the then archbishop of Canterbury, Cosmo Lang, came to visit.

The two May brothers and Ernest Joseph were honoured posthumously by the British government in 2022 as British Heroes of the Holocaust.

Neil Martin, chief executive of today’s JLGB, notes the Kindertransport rescue was taking place in parallel to the Kitchener project, with some Kinder staying briefly in Sandwich before moving on to foster families.

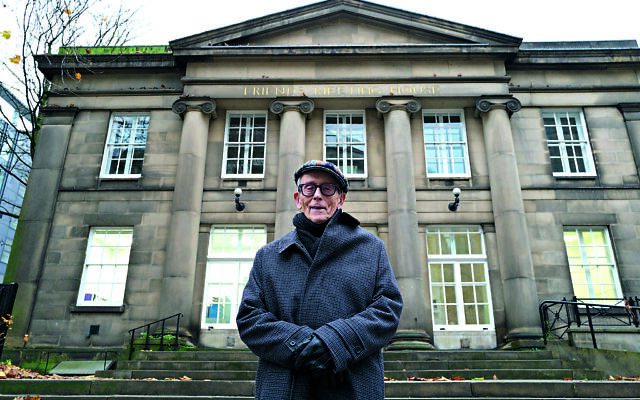

Danny Herman, who now lives in Manchester and was awarded the BEM in this year’s New Year Honours for services to Holocaust education, spent his fourth birthday, 15 September 1939, in Kitchener. His father, Siegie, then 34, had arrived in July that year from Koenigsberg, now Kaliningrad, while Daniel arrived on 2 Septembe with his mother Gretchen.

Herman recalls: “My father had his business, wholesale hosiery, taken from him and instead was working in the Zionist offices in Koenigsberg, helping Jews to fill in their visa applications to leave Germany.

“One day he was visited by officials from the Zionist offices who had heard that my father was on a list of Jews due to be deported the next day to a concentration camp. He said he couldn’t leave without his wife and child, but the officials persuaded him they would look after us and he must leave.”

Siegie escaped capture by a hair’s-breadth: “The SS came for him and he hid in the back bedroom of the flat where we lived. My mother told them he had just gone out for a walk and they believed her. He was very lucky.”

Siegie knew about the Kitchener camp because he had been working on visa applications. He made his way via Poland to Berlin where there was a branch office for Kitchener, and eventually arrived in Britain. He had a qualification in textile engineering, but that was not much use in the rough and ready conditions of the camp.

Instead, says his son, Siegie worked as a navvy, helping to re-tar the roads inside the camp. By the time Gretchen and Danny arrived, there were areas set aside for women and children, but Siegie “thought the conditions were so poor that he managed to borrow money to put me and my mother up in a bed and breakfast place.”

Danny Herman has no memories of the camp, but was later told that on the boat coming over from Hamburg “I lost my teddy bear overboard”. He was “inconsolable”.

Once war began in September 1939, the end was in sight for Kitchener, though it continued to shelter hundreds of Jewish men and a few women and children until May 1940. Then, says Neil Martin, things changed.

“After the Nazi invasions of Holland, Belgium and France in May 1940, public opinion toward the camp soured. Government fears about Nazi spies meant all male refugees (now termed ‘enemy aliens’) not involved in the military or not emigrated were interned. After just 16 months, the camp was disbanded and closed.”

The “extraordinary humanity and resilience” of the JLB leaders provided refuge to thousands of Jewish men in one of history’s darkest periods. Nothing remains of the Kitchener camp today, but its story, now marked in the 85th anniversary of its opening, recalls a remarkable endeavour.

Thank you for helping to make Jewish News the leading source of news and opinion for the UK Jewish community. Today we're asking for your invaluable help to continue putting our community first in everything we do.

For as little as £5 a month you can help sustain the vital work we do in celebrating and standing up for Jewish life in Britain.

Jewish News holds our community together and keeps us connected. Like a synagogue, it’s where people turn to feel part of something bigger. It also proudly shows the rest of Britain the vibrancy and rich culture of modern Jewish life.

You can make a quick and easy one-off or monthly contribution of £5, £10, £20 or any other sum you’re comfortable with.

100% of your donation will help us continue celebrating our community, in all its dynamic diversity...

Engaging

Being a community platform means so much more than producing a newspaper and website. One of our proudest roles is media partnering with our invaluable charities to amplify the outstanding work they do to help us all.

Celebrating

There’s no shortage of oys in the world but Jewish News takes every opportunity to celebrate the joys too, through projects like Night of Heroes, 40 Under 40 and other compelling countdowns that make the community kvell with pride.

Pioneering

In the first collaboration between media outlets from different faiths, Jewish News worked with British Muslim TV and Church Times to produce a list of young activists leading the way on interfaith understanding.

Campaigning

Royal Mail issued a stamp honouring Holocaust hero Sir Nicholas Winton after a Jewish News campaign attracted more than 100,000 backers. Jewish Newsalso produces special editions of the paper highlighting pressing issues including mental health and Holocaust remembrance.

Easy access

In an age when news is readily accessible, Jewish News provides high-quality content free online and offline, removing any financial barriers to connecting people.

Voice of our community to wider society

The Jewish News team regularly appears on TV, radio and on the pages of the national press to comment on stories about the Jewish community. Easy access to the paper on the streets of London also means Jewish News provides an invaluable window into the community for the country at large.

We hope you agree all this is worth preserving.