‘Antisemitism is the passion dead Jews arouse in their killers to kill more of them’

In a lecture at the centre on Sunday, the acclaimed novelist Howard Jacobson says: 'I have lived a long time and seen such things, but never before hysterical glory in the slaughter of sleeping babies'

“I have of late, but wherefore I know not, lost all my mirth.” Hamlet didn’t know why he lost his mirth, but I know why I’ve lost mine. Losing one’s mirth is not something any Jew of my acquaintance takes pleasure in. Noam Chomsky maybe, but he is not a Jew of my acquaintance. Or Ilan Pape, the Israeli Jewish historian who last week wrote, “Hamas had to act and act quickly.”

Unless I misrepresent him, that wasn’t meant to be funny either. Otherwise, laughter is our lifeblood. Black laughter. The blacker, the more the colour of our history, the better. “All right, let’s admit it, we Jews killed Christ,” Lenny Bruce joked, “but it was only for three days.”

That brilliant joke did us a power of good 60 years ago, but what Jew would dare make it today? Now we are back in a time it discredits the Middle Ages to call medieval. Hands up those of you who thought we’d seen the last of the bloodline. “As for myself,” declaims Marlowe’s Jew of Malta, “I walk abroad at nights and kill sick people groaning under walls, sometimes I go about and poison wells.”

That too is joking, Marlowe’s Jew of Malta anticipating Lenny Bruce making ghoulish fun of the calumnist’s slander on the Jews. And that’s another instance of the mirth we have neither the courage nor the stomach for just this minute. I was asked to give this lecture a century or two ago, measured not in time but blood.

“No,” I said. “Yes,” said David Hirsh. So I’m giving it. I didn’t want to give it because I felt I’d given it enough already. Because I am a Jew, many of the conversations I have are in my own head. It’s safer there. “Do me a favour,” one of my familiar voices said, “talk about something else, no more Israel.” “I don’t know how I can talk about antisemitism without talking about Israel,” I replied, though I know some Jewish writers try.

Sweet, don’t you think, that there was a time when to accuse Jews of not being able to make a pencil box was what anti-semitism was. I’m glad my mother and father aren’t alive to hear what the Jew haters accuse us of now

Gaza is the new Golgotha. But then you’ll end up talking anti Zionism. “That’s right, I will,” I said. Anti-Zionism is the new antisemitism. Oh, so you support the settlers. I don’t know who said that. It wasn’t a voice I recognise. “I don’t have to support Israel’s grave mistakes to understand its grave necessity and admire the grand idealism of its founding,” I replied.

Judge any state by the mistakes it makes and the whole world’s rotten. What if Israel is all mistake?

I did warn you I had lost my mirth. The next voice to try to dissuade me from giving this lecture was the most persuasive. “You’ve used up all your material on antisemitism,” she said. If you’re not careful, you’ll end up telling that story about how your moral tutor at Cambridge called you Himmelfahrt one week and Finkelstein the next.

I made a note reminding myself not to tell the story of how my moral tutor at Cambridge called me Himmelfahrt one week and Finkelstein the next, though I have a feeling you might have liked to hear it again. It dates from a time when antisemitism wore an almost benign aspect, as when the woodwork teacher held up the pencil box I’d been making for three and a half years and said, “Why are Jew boys so gammy handed?”

But there I go again, sentimentalising the past, gammy handed. Our parents, who were all covenant makers and upholsterers, went berserk. Sweet, don’t you think, that there was a time when to accuse Jews of not being able to make a pencil box was what antisemitism was. I’m glad my mother and father aren’t alive to hear what the Jew haters accuse us of now.

Leave the continent, say. Go somewhere else. Do you have anywhere else in mind, I’d ask? Of course they do. Israel. Ah. That sound denotes the return of my mercy. Ah. I should have said that the other thing I feared losing of latest language. How to find words. How to find an adequacy of words. I don’t just mean to recount the massacre of October 7th, I mean to describe the orgiastic pleasure some people took and continue to take in the sight of Jewish blood.

And when I say some people, I’m not just talking about Hamas card-carrying Palestinians. So who am I talking about? Ladies and gentlemen, I wish I knew what species of being they are, or to what branch of humanity in any they belong. I have lived a long time and seen such things, but never before hysterical glory in the slaughter of sleeping babies.

We need new words, but the old ones are all we have. When in trouble, go to Shakespeare. I would not have given it for a wilderness of monkeys, says Shylock, of the stolen ring Jessica is reported to have sold to buy a pet monkey. To a Jew, the rapacious, ungovernable animal wilderness is all that waits on the other side of law and language.

And what was it but the wilderness that burst back into Israel on Saturday, October 7th? And what are half our university campuses but the wildernesses of abandoned thought? Do you remember when we feared a jackboot? Now it’s a textbook. Whether or not the philosopher Theodor Adorno really did advise against the writing of poetry after Auschwitz, there is a cause for pause, there is a case for pausing before speaking, and then maybe not speaking at all.

The great Israeli novelist Aharon Appelfeld, who was transported to a labour camp when he was a boy, and afterwards spent three years in hiding in the forest, wrote of learning silence as a mode of forgetting, burying, as he put it, the bitter memories deep in the bedrock of the soul, in a place where no stranger’s eye, not even our own, could get to them.

How to speak of unimaginable barbarity in a way that reaches down to the bedrock of the soul? Well, here’s how not to. Our governments are not only tolerating war crimes, but aiding and abetting them. There will come a time when they are held to account for their complicity. But for now, while condemning every act of violence against civilians, and every infringement of international law, whoever perpetrates them, our obligation is to do all we can to bring an end to the unprecedented cruelty being inflicted on God.

Unprecedented cruelty, we’ve seen it only a day before, worse. So much for the way, for the way with, so much for the way with words of the two thousand artists who sound, who signed the now infamous Artists for Palestine letter. So closed of mind and dead of heart, it could have been penned by Jeremy Corbyn.

The next time you meet an artist, ask them to read those words. But for now, while condemning every act of violence against civilians, ask them to read it in a way that doesn’t sound as though they’re talking about someone stealing their mobile phone. Was there not one among the 2, 000 artists who knew that not to use words with feeling is not to feel?

But then they aren’t using words as we understand words. They are dancing. We know the dance well from Milan Kundera’s novels of leftist delusion, the dance of deluded brotherhood in criminality and slander and lies. No one will listen to you, the guards at Auschwitz mocked Primo Levi, and even those who listened won’t believe.

In a monstrous scream, Levi finds himself back home, telling his friends and family what he’d seen. But, and I quote, they are completely indifferent, speak confusedly of other things among themselves, as if I was not there. They don’t listen to his words because they can’t afford to hear them. But what happened in Israel on October 7th?

wasn’t wrapped in report. It wasn’t one man’s version of confused events, perhaps distorted over time. Here, enacted before our eyes, whichever channel we fled to, were events that defiled, that defied all argument or dissent. Wrong again. Now we know that where there is sufficient hate, anything can be denied, minimised, justified, glided over, forgiven, explained away as simply the bad effect of a far worse cause, a parenthesis in a story those who have read nothing else must go on telling.

Not pausing to weep or search their souls, if only to a field of horrors for half a day, and compassion for half another, the cheer squads of terror applauded the gunning down of 40 innocent babies in their coffins. Innocent, do I hear you say? I know two thousand artists who will put you right on that.

There are no innocent Israelis. We do not say the same about the Gazans we see lost and broken outside the ruins of their houses. They, too, fill us to the brim with despair. We will not begrudge them the tears they begrudge us. Humanity can’t be traded away. Their faiths today are differently. Unbearable, but unbearable.

Nevertheless, there is no point being a Jew if one doesn’t feel that. We didn’t leave the wilderness in order to jabber jubilantly over corpses so long as they aren’t ours, but, and there’s always a bot. These are the words of that most elegant and humane of writers. Dick Grossman. The occupation is a crime, but to shoot hundreds of civilians, children and parents, elderly and sick in cold blood, that is a worse crime.

Even in the hierarchy of evil, there is a ranking, there is a scale of severity that common sense and natural instincts can identify. 2000 artists condemning every act of violence denies that hierarchy. If some crimes are worse than others, those can only ever in the eyes of the apologists be the crimes Jews commit and crimes committed against Jews we now know are not crimes at all.

I’m aware I have Allied Israelis and Jews away now. Finally with that, with that thread, bear subterfuge beloved of academic anti-Zionists, that they are not anti-Zionist, antisemites. As the definitions slide and interchange, as cries of kill the Jews or gas the Jews ring out across the world, that veil of pretence has been shredded once and for all.

No you don’t have to hate Jews or the Jew in yourself to hate Israel. It just so happens that you do.

It chills me to the bone to say this, but these last weeks have taught us a new definition of antisemitism. Antisemitism is the passion dead Jews arouse in their killers to kill more of them. This is the drumbeat of the wilderness.

Blood begets blood. Not for being too rich or too strong or too weak, or too clever, or too arrogant or too influential. Not for being circumcised or for fathering Christianity, or for controlling the world’s media. Not even for voting for Netanyahu of the Jews. Detestable. They are detestable because there is a history of someone detesting.

Antisemites, David Rich, head of policy at the Community Security Trust, is reported as telling the journalist Nick Cohen, are getting excited by the sight of dead Jews. Sorry to be blunt, he goes on, but I am in an uncompromising mood. They’re not angry because Israeli soldiers have killed Palestinians.

The sight of Hamas murdering Israeli civilians has exhilarated them instead and filled them with joy. Dave Rich, who doesn’t overwrite, and doesn’t exaggerate, but knows about the problems the Left has with Jews, is not frightened to call antisemites antisemites. And it’s not just Garzans who are joyful.

No less exhilarated are the progressive academics and professional problemists, the mouthpieces of social media claptrap, who were paid to teach the young how to think, but teach them only how to spot and hate a coloniser in a young. How come? How deep? How long? We blunder bewildered into a dense jungle of fowls.

How, less than a century after the world said ‘never again’, has again managed to make it back out of the wilderness, alive and ready to rejoin the dance. The devil of despair whispers in my ear, because it will always be so. Is that an explanation, I whisper back; no, it’s just a statement of fact. So there is no explanation, is that what you were saying?

Either that, or there are too many explanations. Either way, it paused. Either way what? Either way you will break your heart trying to understand. Which leads me where exactly? In danger, but you know that. Thanks very much, I say, backing away. He takes my arm. There’s one thing you can do, he says. Show a bit of self-respect.

Stop apologising. Loving your neighbour for hurting you is a pathology. Are you accusing me of being a self-hating Jew? If the cap fits. You are not permitted to say self-hating Jew, I remind myself. Why not? Because… Because… But I have temporarily forgotten why it’s not permissible to say self-hating Jew.

But it will come back to me. Any history of the Jews that isn’t the history of their inner life isn’t the history of the Jews at all. By inner life I don’t only mean their introspection and bookishness, their valuing the mind over the body, their choice of an invisible god of words over a painted icon, their hatred of the moral wilderness.

I mean the complex psychology of self-blame, which again and again has enabled them to find perverse realisation in adversity, and an exquisite poetry of loss. Their cities sacked by Nebuchadnezzar, their temple destroyed, and they themselves led into abject captivity. In Babylon to demoralised Israel, acts might easily have given up on a God who had promised them everything, but now by his silence, pretty well admitted to being the second-best God to the Babylonian one.

What worth in being a chosen people this time? But self-criticism is a powerful tool. What if Jews looked inward and asked, ‘What if they had brought this catastrophe on themselves by moral laxity and some indiscreet, idle worshipping of their own?’ Victim blaming, we call that today. But in the case of the Babylonian exile, those doing the blaming were the victims themselves.

Imagining they were in Babylon, not on the say so of some superior foreign deity, that because they had incurred the wrath of their own god, they kept alive belief in his omnipotence and law, and turned what had happened on its head, finding an exquisite victory in defeat. By the waters of Babylon they wept, but by the waters of Babylon they also found renewal.

Through their transgressions, they came to know themselves, revising their laws, entrusting their history to scholars, scribes and Talmudists, who turned an old religion of animal sacrifice into a new, portable faith of words and contemplation, and thus, by virtue of their contrition, once more becoming, in their own eyes, chosen of God.

There are Jews who wish we’d kept faith with our genius, to rise from the ashes of defeat. and not found a way at last to win. People, the writer Dara Horn tells us, love dead Jews. Live Jews, too, love dead Jews. I recall a Jewish Book Week years ago in which the audience was invited to nominate their favourite Jewish book of all time.

You can guess the answer. It wasn’t written by anybody in this room. It was the diary of Anne Frank.

Had we only lost the Six Day War, we might have produced a thousand diaries of Anne Frank, and every one a bestseller. Instead, the schmucks we were, we went and won it. The price for which was finding ourselves occupying land we didn’t dare give back, for fear it would be a launching pad for a seven, and then an eight, and then a nine day war.

Schmucks the second time, imagining we could put an end to that cycle. That a muscular Jew was an unwelcome prospect to Arab nations, accustomed to seeing him as a semi-castrated pushover who poisoned their wells, was only to be expected. More surprising and problematic is that there are Jews who have difficulty with this new reality too.

Let’s admit that two thousand years of Christian antisemitism have prepared the ground well for whatever version of it comes next

Israel is very rude and assertive, we said, when we first holidayed in Eilat. We wanted some cunny lemony from Cheetham Hill or Temple Fortune to wrap our lap kiss. We were more fun when we were so many weedy, bespectacled, elderly singers seeing ourselves as a Hasidic rabbi in the eyes of Annie Hall’s kosher granny, or Portnoy, bent double over the weekend roast.

Of course, we didn’t really like ourselves in those guises either, but at least that way we got a laugh. I am still circling the question of Jewish self-hate. Call it self-blame and no one minds too much. My punishment is more than I can bear, said Cain when he bore it, and self-scrutiny got us in and out of Babylon in reasonably good shape.

But I wonder if there is a progression from self-criticism to self-suspicion to self-hatred to self-disgust, whose terminus ad quem turns out to be the very antisemitism that set this psychological process in motion in the first place. Maybe some of the Jews among the reprehensible 2,000 artists liked themselves once.

Hard as it is to imagine why. Quoting TS Eliot might be tactless in this context, but these words from Little Gidding are appetite. We shall not cease from exploration, and the end of all our exploring will be to arrive where we started. Tormented by anti semitism into misgivings about who we are and have a right to be, winning where we are far more comfortable losing, we become at last indistinguishable from our tormentors, seeing the Jew they see, hating the Jew they hate, and as often as not, going out of our way to find Jews who are more loathsome still.

What, if it is not self hate, are we to call the condition dramatised in Farewell Leicester Square? A novel, by a Jew, about Jews making one another skin creep, written in 1935, a few years before what some call the Occupation, but already not a good time for Jewish writers to be careless in their words. I quote, He watched Lou’s foot, in a pointed yellow shoe, tread the accelerator.

Observed at the same time, the width, the perfect hang of Lou’s family tailored trousers, the slick fit of his coat, with its sharply built up shoulders. Out of this rose Lou’s neck, broad and squat, with small, thick ears sticking out on either side like handles. Black, pretty hair, embalmed in a rich oil. On first meeting him, Alec had been repelled by Lou’s appearance.

Why should he find them more offensive than, say, some tan haired youth, low browed and spotty faced, with a dangerous animal vacuity in his light blue eyes? Did Englishmen feel as much resentment at the sight of unpleasing Englishmen as he did confronted with the minutest failing of his own race? Lives there a Jew who was not on occasion felt something of the repulsion Alec feels, and then searched his soul and wondered if Jews alone feel this way about their own planet.

Alex knows the answers of that. No. The English do not experience the shame and embarrassment Jews experience when confronted by a version of themselves they cannot bear. They are not out there looking for it. They are not wondering if what’s been said about them for centuries is true. The English are not an endangered species in the human zoo, and more to the point, they are not their own zookeepers.

On the face of it, what Alex convinces is not self hate, it’s loon hate. But would Alec hate Lou quite so inordinately, and with so little cause, if the same small barrel didn’t contain them both? Lou hate is Jew hate. In every Jew so self aware as antisemitism made them, Jews see a reflection, as often as not a gross caricature of themselves.

Fifty years earlier, Freud wrote to a friend about two Jews he saw on a train, one who, and I quote, taught the same way I’d heard others taught before, cut from the same cloth from which fate makes swindlers, cunning, mendacious, kept by his adoring relatives in the belief that he is a great talent, but unprincipled and without character.

In the course of the conversation, I learned that he hailed from Mezirich, the proper compost heap for this sort of weed.

Freud’s excuse when he wrote that was that he was 16. Remember how you felt at 16 when you saw a Jew who was not like you and yet somehow, just somehow, was. A Jew from some primitive place, a compost heap, traces of which adhered to you still and always would. Between them, these two evocations of acutely Jew conscious Jews, one wishing to be English, one at home in Vienna, but not wanting to be reminded of his antecedents in the East, both disgusted not to say morally disfigured by consciousness of this or that version of Jewish vulgarity, paint a competent picture of a Jew who can never be Jewishly comfortable in his own skin.

Self-hate is not the final word in either case. But it’s an illusion to suppose it’s not there in the mix. Just admit it, you Jews who must tell the world that Jews have no business in a country that they should have put behind them actually and imaginatively centuries ago. Just admit that, however lucid you think your analysis, you are as compromised by your longing for a Jew-free future as the theology crazed settlers you despise are for a Jew dense past.

Let me come clear. Of the crime of over-Jewing one’s own people, I too am guilty. I see a Jew who looks stereotypically Jewish or believes in what I take to be a stereotypically Jewish manner and I recoil. If he happens to be driving a Rolls and smoking his cigar, I am tempted to cover my own face before wondering how I might cover his.

Discussing a popular reality TV programme with gentile friends once, I expressed surprise. A, that they liked the show, and B, that they liked its host, a wealthy Jewish entrepreneur I will call Sir Morris Mountebank Fink. I banged the table in irritation. Could they not see that at an ostentatiously, ostentatiously wealthy.

Boastful and abrasive Jew, rewarding contestants for their business nows. He was perpetuating every anti Jewish myth. The room felt quiet. My gentle friends exchanged looks of puzzlement. Sir Morris Mountebank Fink, Jewish? Well, I’m sure. There is no need to labour the point. Where others saw a man like other men, I saw only a Jew.

I accused Sir Morris of doing the work of antisemite for them. But the true antisemite in the room was me. This is a circularity we frequently encounter in Jewish discourse. One Jew charging another with exposing the Jewish people to the ridicule he subjects them to in his own heart.

Take the responses to Philip Roth’s Portnoy Complaint. Portnoy’s Complaint when it appeared in 1969. Marie Erkin arguing that there was, quote, Little to choose between Bels is and Roth’s interpretation of what animates Portnoy and the great scholar Gershom Scholem declaring that this is the book for which all the antisemites have been praying.

With the next turn of history, not long to be delayed. This book will make all of us defendants at court. It will be quoted to us and how it will be quoted. They will say to us, here, you have the testimony from the testimony from one of your own art. From here you have the testimony from one of your own artists, an authentic Jewish witness.

I love Gershom Scholem, but an authentic Jewish witness to what? Our filthy habits? Our propensity for comedy? Is history going to turn on us again for what we do in the bathroom and then have the nerve to make Jews about it? There you go. I should stop my lecture at that point. Is history going to turn on us again for what we do in the bathroom and then have the nerve to make jokes about it?

What looks as though it’s coming next? It could be another tough millennium, which is further reason we don’t need disintegrating Jews projecting their own inner chaos on us from the inside

Or is it you, not history, that can’t abide the Jewish body? I make no comparison with myself and Philip Roth, but when I had found the Jewish degeneracy of a minor libidinous sort in my early novels, I was accused of washing my family’s, that’s to say the Jewish people’s, dirty linen in public. There was, it seemed, some Jewish practices which it was the responsibility of every Jewish writer to conceal.

Dirty linen. What did we do before we loaded our washing machines that no other people did? And that we needed not to talk about. What was our terrible secret? Roth’s answer to his critics was typically robust. Not always, but frequently, what readers have taken to be my disapproval of their lives, lived by Jews, seems to have more to do with their own moral perspective than with the one they would ascribe to me.

At times they see wickedness where I myself had seen energy or courage or spontaneity. They are ashamed of what I see no reason to be ashamed of, and defensive where there is no cause for defence. Were this lecture about anti-Zionism, which it only tangentially is, I would be in here, with the mealy-mouthed shame I ascribe to Jews for whom the energies of the first great Zionists were no more than the depredations of colonisers.

This is not to be confused with any embarrassment Jews might have felt reading Portnoy. If Portnoy’s rude energy gave sucker to anti Semites who thought Jews had unhygienic habits, that’s nothing compared to the sucker the Jewish anti Zionists give to anti Semites who believe Jews are the ones who love killing babies.

That the sexualized Jew, and latterly the warrior Jew, should power Jewish anxiety is ironic when you remember how bad it once made us to be seen as feminized and afraid. But that’s the dialogic nature of self-contempt. We are forever not liking what we did to correct what we didn’t like about ourselves last time.

The novel from which I read that extract is particularly astute about the way a Jew will blame someone else for appearing to see Jews when he cannot bear to see himself. You will remember Alec, who regarded his two two speedy Jewish friend with distaste. This is his upper middle class non-Jewish wife Catherine.

It was always going to have to be a non-Jewish upper-middle class wife called Catherine whom he married, describing how hard he used to live with her. You think I exaggerate, but I don’t even look at any Jews we see casually in the street. Or I’m looking at them coldly, or with repulsion, or something.

He’s always saying that he wants Jews to be treated like any other human being, but at the same time he’s like a cat on a hot brick, all the time about himself and all the others. He never forgets the thing for one moment. I’ve discovered it’s always there at the back of his mind, whatever he does and wherever he is.

One Jewish theatre director boycotting another Jewish theatre director… adding your signature to that of the serial signer Miriam Margolyes, who would boycott a bagel if it had been baked in Israel

It haunts him. And now it’s beginning to haunt me. I actually feel guilty when we happen to meet some really ugly or ill-behaved Jews. As if it was obscurely my fault. No fun for her, no fun for him. It’s a mess how Jews look at Jews. And it’s been messed up by our interjecting how others have for too long looked at us.

Let’s admit that two thousand years of Christian antisemitism have prepared the ground well for whatever version of it comes next. And if the psychoanalyst Stephen Frosch is right, or at least if some of the psychoanalysts he quotes in his fine book, Hate and the Jewish Science, are right, that, “The function of the Jew for the antisemite is to secure the inner world against doubt or dissolution by constituting a mythological external enemy.”

What comes next? What looks as though it’s coming next? It could be another tough millennium, which is further reason we don’t need disintegrating Jews projecting their own inner chaos on us from the inside.

Speaking of whom, remember Jonathan Miller, the son, as it happens, of Betty Miller, who wrote Farewell, Leicester Square, and himself the author of that accursed, deracinated joke: I’m not really Jewish, just Jew-ish.

I’m not like that. I’m not really a Jew, just Jewish. Many of the Jews I hung around with in the 1960s, boys from the northern ghettos, hankering for a less parochial scope for their talents, related to that joke. We repeated it to one another ad infinitum. That was exactly how we felt, aged 18.

It was only as time, as time went by, that we realised it hadn’t really been a joke. Jonathan Miller genuinely didn’t feel he was a Jew and needed people to know it. Some Jews turned on Jewish quietly. They changed their names to Xavier and ran to hounds in rural Berkshire. Some even paid for plastic surgeries.

Jonathan Miller kept his name and nose, and like people who are compelled to take their clothes off in public, wanted to be seen for what he wasn’t in full view. Freud, who didn’t much like Jews from the old country when he was sixteen, felt differently in later years. In some place in my soul, he wrote, in a very hidden corner, I am a fanatical Jew.

Anyone hoping Miller would eventually find a similar hidden corner in his soul would be disappointed.

Although my family were Jewish and I am genetically Jewish, he told Dick Covert in a famous television interview in 1918, I have absolutely no subscription to the creed and no interest in the race. I don’t believe in race and I find racial notions so objectionable that I can’t think of myself as being Jewish in that way.

I’m Jewish for purposes of admitting it to antisemites. I’m not prepared to be Jewish in the face of other Jews. I’m in an argument with myself about the cold, robotic intellectualism of those words. On the one hand, I find them utterly repugnant, disingenuous, pusillanimous, soulless, self delighting, without humility, without humour, and without honour.

And if you want me to come off the fence, I find them mind numbingly stupid. In 1918, Miller was 45. Which was too old to be showing off his dazzling, free thinking cosmopolitanism. Subscription to the creed, indeed. How many practicing or part practicing Jews would say they subscribe to a creed? Or hold race to be a concept essential to the way they live?

Even the most devout Jews today wear their Jewishness more pragmatically than that. On the other hand, is it not sad that Miller had so little concept of how affiliation operates and what it might be like to be a Jew of whatever complexion, among other Jews, and what the consolations of such an amity might be?

As for why he did not, why he refused his Jewishness in the face of other Jews, or in what spirit he would affirm it only for those who hated it? I’m not sufficiently versed in Devi in diseases of the psyche to understand, but the sneering in which he descended over time was its own retribution. I’d like to say he gave his, gave away his humor and he gave away his Jewishness, but I don’t know that.

I only know that his, I only know that his face grew longer as he aged. A lost and peevish soul, brilliantly gifted, infinitely unhappy, complaining of being ignored even as he directed opera and theatre on the world’s greatest stages. A man able to call on a rich Jewish store of amusement might have been able to see the ridiculousness in such self pity.

But he had no subscription to the Queen. The ultimate betrayal for me, a betrayal of his own integrity no less, was his decision to sign a letter calling for the boycotts of the Israel based Habima Theatre’s Hebrew performance of The Merchant of Venice in 2012. Multiply the ironies of that. One Jewish theatre director boycotting another Jewish theatre director, endeavouring to stop The Merchant of Venice, The Merchant of Venice, of all plays, from being performed in London. With enough absurdist clues there to make you think again, Sir Jonathan. Not least the fact that you were adding your signature to that of the serial signer Miriam Margolyes, who would boycott a bagel if it had been baked in Israel.

Hath not even a faint hearted Jew eyes? Or had the ish in Jewish grown so big now that it could not resist one last gesture of disownment? Except that it was more than disownment. It was a blow aimed not just at art, the world beyond the wilderness to which he’d given his professional life, but at the Jewishness in which he claimed to have no stake.

I’ve concentrated a bit on Jonathan Miller because I see him as exemplary of the educated Jewish self-dislike that contributes to what his mother described as the perpetual uneasiness in which a Jew lives. I don’t say he should have shown his own people more love. One cannot dictate the laws of kinship and affection to someone else.

And indifference isn’t hate. So, even taking into account his support for that unconscionable boycott, I don’t call him an antisemite. Like many Jews who position themselves as he did. Above the fray of faith. Too grand for ancient grudges, except when they are the grudges felt by someone else. Driven by a strange self disgust into the sickly sweets of masochistic complicity with those who want you gone.

Jonathan Miller was never really antisemitic, just… antisemitic ish, which might be all it takes if there are enough Jews holding hands with people who prefer dead Jews to live ones to tip their back into the wilderness.

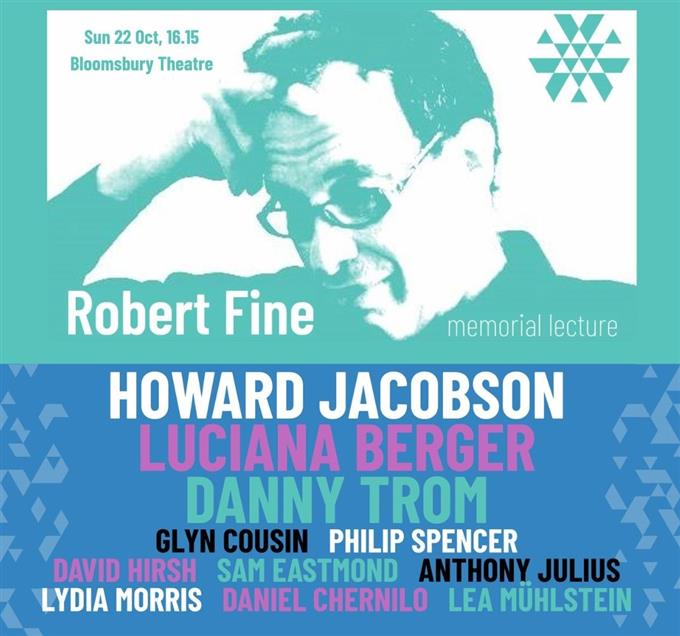

- Howard Jacobson was speaking at London’s Bloomsbury Theatre on Sunday as part of a series of lectures and talks organised by the London Centre for the Study of Contemporary Antisemitism

Thank you for helping to make Jewish News the leading source of news and opinion for the UK Jewish community. Today we're asking for your invaluable help to continue putting our community first in everything we do.

For as little as £5 a month you can help sustain the vital work we do in celebrating and standing up for Jewish life in Britain.

Jewish News holds our community together and keeps us connected. Like a synagogue, it’s where people turn to feel part of something bigger. It also proudly shows the rest of Britain the vibrancy and rich culture of modern Jewish life.

You can make a quick and easy one-off or monthly contribution of £5, £10, £20 or any other sum you’re comfortable with.

100% of your donation will help us continue celebrating our community, in all its dynamic diversity...

Engaging

Being a community platform means so much more than producing a newspaper and website. One of our proudest roles is media partnering with our invaluable charities to amplify the outstanding work they do to help us all.

Celebrating

There’s no shortage of oys in the world but Jewish News takes every opportunity to celebrate the joys too, through projects like Night of Heroes, 40 Under 40 and other compelling countdowns that make the community kvell with pride.

Pioneering

In the first collaboration between media outlets from different faiths, Jewish News worked with British Muslim TV and Church Times to produce a list of young activists leading the way on interfaith understanding.

Campaigning

Royal Mail issued a stamp honouring Holocaust hero Sir Nicholas Winton after a Jewish News campaign attracted more than 100,000 backers. Jewish Newsalso produces special editions of the paper highlighting pressing issues including mental health and Holocaust remembrance.

Easy access

In an age when news is readily accessible, Jewish News provides high-quality content free online and offline, removing any financial barriers to connecting people.

Voice of our community to wider society

The Jewish News team regularly appears on TV, radio and on the pages of the national press to comment on stories about the Jewish community. Easy access to the paper on the streets of London also means Jewish News provides an invaluable window into the community for the country at large.

We hope you agree all this is worth preserving.