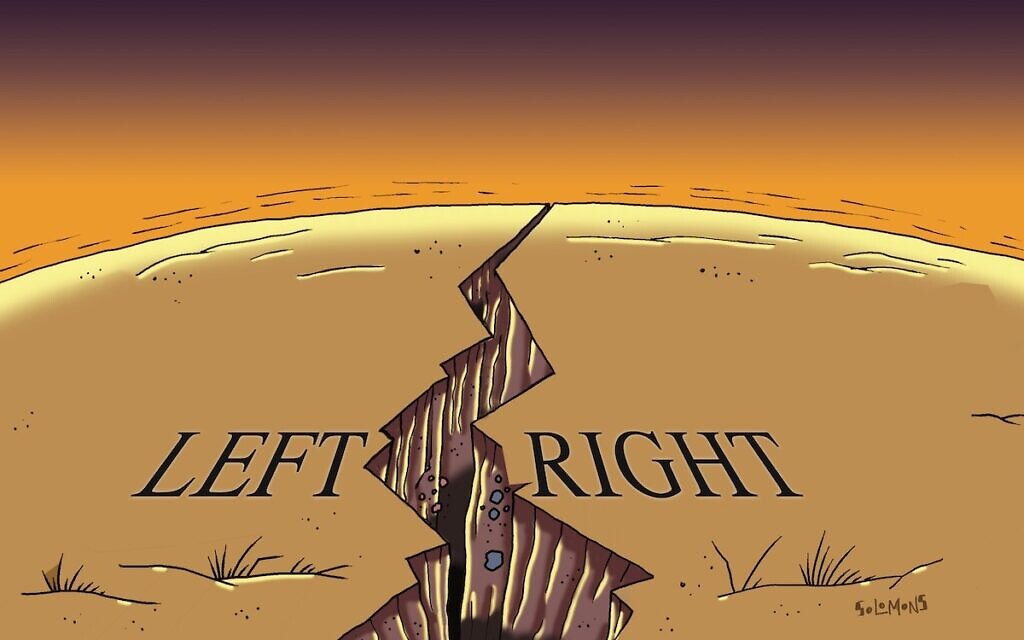

Jewish News special report: The great divide

Does our community still have a centre ground or has it become unleadable?

Our diverse community has long argued over a wide range of issues, not least concerning Israel and other highly politicised topics.

Like wider British society, the community has its left-wing and its right-wing. That bit is not new.

What is new, it seems, is a sense that shifts are under way, that left and right are moving further and further apart, that the centre has narrowed or disappeared, that our community is becoming unleadable, that politically we have grown morbidly intolerant of each other and that tools to fight antisemitism are now being used by some to fight those with different views on Israel.

Get The Jewish News Daily Edition by email and never miss our top stories Free Sign Up

Is that a correct reading, we wondered, or is it just paranoia, an altered sense of reality cooked up by social media?

It is several years since Jewish News took the community’s pulse on the left-right divide.

Now feels like a good time to do so again.

The JCORE vote

The Board of Deputies this year unveiled a landmark report into racial inclusivity in the Jewish community. Months in the making and much heralded as a first-of-its-kind effort, the Commission made a series of recommendations on how best to help Jews of colour.

Excluding the Jewish Council for Racial Equality (JCORE) from Board membership was not one, yet with the ink on the Commission’s report barely dry, that is exactly what happened last month. Why, after so much was made of the Commission?

To some, the JCORE vote was less about race and more about whether its leadership liked the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance (IHRA) definition of antisemitism, or if a JCORE intern attended the Kaddish for Gaza in 2018.

Richard Cooper, representing Portsmouth and Southsea Hebrew Congregation, wondered aloud whether JCORE “gives help and comfort to the enemies of the Jewish people and of Israel”.

There was something else. JCORE said it was “outward-looking”, but that was a problem for Jerry Lewis, a former Board vice-president, who said he had “never seen them do anything of any great value to us as a Jewish community”.

To others, the vote was evidence of a deepening communal rift, between a splintering and radicalised left and an organised and energised right, out to stop left-wing progressive groups such as JCORE from having a seat at the table.

Joseph Cohen, who co-founded Campaign Against Antisemitism and now runs the Israel Advocacy Movement with a large online following, pays “zero attention to the Board” but said the JCORE vote popped up on his radar. “What kept coming up was the people involved and their stance on Israel,” he says. “It wasn’t about their stance on racism. It had more to do with the individuals than with the values of the organisation or the change it was trying to create.”

That doesn’t surprise JCORE’s Dr Edie Friedman, who founded the organisation in 1976. “Divisions in our community reflect divisions in society,” she says. “Recent years have been particularly divisive, with differing opinions on Israel, what constitutes antisemitism, and how best to combat racism.”

Laura Janner-Klausner, a prominent Reform rabbi, thinks the JCORE result came down to ignorance, “not down to any broader issue”, but Hannah Weisfeld, founding director of the left-wing Zionist group Yachad, disagrees.

“Israel still defines everything,” she says. “The JCORE vote was all about Israel. A past employee once did something anti-Israel, a trustee once shared a platform with someone who bad-mouthed Israel… It wasn’t about racism.”

For Keith Kahn-Harris, a sociologist at the Institute of Jewish Policy Research (JPR) who wrote the go-to book on Jewish communal battlelines over Israel in 2014, the JCORE vote revealed the paradox of the Board of Deputies.

“Unlike in a democratic parliament, deputies can vote on who to exclude as constituents,” he says. “Voting not to admit JCORE is like MPs voting not to recognise the constituency of Sunderland South.”

The state of the left

JCORE’s natural supporters are progressive, with progressive values, says Daily Mail City editor and veteran of Jewish communal politics Alex Brummer, in discussion about the Jewish left and any generational differences.

“There have always been big Jewish names on the old left,” he says: “You saw them around Corbyn’s team. It goes back to the 50s. They’re a permanent presence, permanent extremists if you like, not just here but in the US too.”

The “younger woke generation are more socially conscious, more into social equality than some people have traditionally been in the Jewish community,” he says. This is “particularly strong” in the Reform movement.

“Kids who’ve been through RSY… pick up different values to kids growing up traditional Orthodox: social equality, gender equality, racial equality, a fairer society, giving something back. JCORE supporters would probably come under that.”

For Paul Charney, outgoing chair of the Zionist Federation, “the new woke generation automatically sits in that left-wing pocket” and “their priority is to see Israel as an open, liberal society, with social equality, whether you’re Jewish or not”.

By contrast, he says “the older generation thinks Israel must maintain a Jewish majority, which is the exact antithesis of what democracy is, but it’s also an anomaly that democracy in Israel can only withstand if there’s a Jewish majority”. Oldies, he says, “know that without a Jewish majority, you’re just not safe in the Middle East”.

Cohen thinks the young may be misunderstood on Israel. “I often hear that they’re critical, but that’s not shown in the data,” he says, before adding that there is “a move away from being passionate about Israel, Judaism, Jewishness, with a drift by some to assimilation… that’s the real problem for the community.”

Others on the right see the new left-wing Jewish generation less flatteringly, with Likud UK chair Zalmi Unsdorfer describing “a large plurality of godless, faithless Jews, with apartheid views, who couldn’t care less what happens to Israel”.

They “probably correlate to critical race theory and all the other things the young are prognosticating”, Unsdorfer says. “It’s not just Judaism and Israel, it’s everything.”

Cohen says today’s left-wing Jewish critics “make a lot of noise, shock their parents, and dominate the news cycle by taking direct action”, but adds that they “lose support as they become more critical of Israel”.

For Jewish barrister Adam Wagner, who specialises in human rights, their criticism is understandable. “I don’t think the temperament of a typical Jewish 20-year-old has changed,” he says. “The politics has changed. The occupation has changed.

“When I lived out there on a kibbutz 20 years ago, there were still the entrails of a peace process. There was something to protest for, not just protest against.

“Today, there’s a generation of young British Jews trying to find a vision for Israel that fits with their liberal ideals. That’s more difficult than it was 20 years ago, because who do they get behind? Where’s the vision? Where’s the hope?

“I imagine they’re equally uncomfortable at university. I really don’t think they’ll just accept the occupation – it’s a terrible, immoral situation and very hard from a liberal perspective because of what’s happening in the occupied territories.”

For Britain’s Jewish centre-left looking beyond Israel, activists are making it hard for them to reconsider the Labour Party, which is now under new management.

“There is still pushback from online activists like Labour Against Antisemitism and Gnasher Jew towards any Labour figure, regardless of where they stand, if they remained a member during the Corbyn years,” says Kahn-Harris. “It’s difficult to know who these activists’ constituencies are, whether they’re sizeable or not.”

The state of the right

There seems little of controversy in Yachad deputy Amos Schonfield’s view that most communal groups belong to “a mainstream or sensible right” that is broadly conservative, pro-immigration but a bit cynical of a wider progressive agenda. Yet time and again, in conversations with figures from both the left and the right, both on and off the record, several themes kept emerging:

• The 2014 war in Gaza gave birth to several now-strong grassroots groups – most notably Campaign Against Antisemitism (CAA) – who were strident, focused on taking on antisemitism through the courts in a way that hadn’t happened before. These were formed by those who felt the Board’s response to Hamas attacks was not strong enough.

• Corbyn’s tenure emboldened and ‘mainstreamed’ right-wingers active online, some of whom hold views that would have been seen as problematic before.

• In the past three years, the right-wing ‘caucus’ at the Board has grown not in number but in organisation, displaying better preparation ahead of key votes and fronting seemingly viable candidates for key roles.

• The right has an increasingly urgent problem to address with its racist fringe, not least because well-known far-right figures such as Tommy Robinson are attaching themselves to right-wing community activists in public.

• Prominent right-wingers are being accused of deliberate divisiveness.

A deputy from a mainstream left-wing organisation and member of the Board’s defence division, speaking anonymously, describes a group of deputies on the political right – known as ‘The Caucus’ and coalesced through WhatsApp – as “basically a bunch of vigilantes, with no concern for Jewish communal unity”.

“They’re extremely ideological, use the language of security and defensiveness, and see everything as a threat. It’s an extremely binary worldview. You’re ‘supporters of Israel’ or ‘opponents’, the latter being anyone who criticises any Israeli policy.”

Interestingly, Wagner says the occupation can now be “isolated” from Jewish communal left/right positions, “particularly now it’s taken on a real religious-extremist aspect, this hilltop youth approach to settlements, a Greater-Israel, just-read-the-Bible approach indulged by Netanyahu and Bennett”.

He says “that is something a lot of British Jews, no matter where they are on the political spectrum, find very concerning, and is not something they support”.

Leading progressive campaigner Andrew Gilbert advises viewing the community’s right-wing against a backdrop of Trump, Corbyn, Brexit and Bibi. “We’re moving out of those paradigms,” he says. “We’ve been fighting fires that aren’t going to be there soon.”

Figures on the right, he adds, have started using the IHRA definition of antisemitism “as a kind purity test” and are taking aim at Yachad, which won Board membership several years ago with more than two-thirds of the vote.

“The centre and left don’t understand the [right-wing] argument that Yachad isn’t part of the mainstream Jewish community,” he says. “The right-wing group at the Board fixates on it. They don’t see Yachad as any different to Jewish Voice for Labour.”

The Corbyn effect

Almost everyone agrees that Jeremy Corbyn’s Labour leadership affected the politics of the community, and most say things “shifted right” as a result.

Kahn-Harris says the broad consensus against Corbyn even suppressed communal conflict for a while. “It was a defining issue on both the Jewish right and left, prompting new alliances and coalitions.” Wagner agrees that Corbyn had everybody “singing from the same hymn sheet… You had people like me, on the liberal left, and people on the right, like the ZF, all saying the same thing”.

One of the reasons he became so involved in the Labour antisemitism issue, Wagner says, was because he “felt like there had to be a voice on the human rights perspective from the left, not just from the centre or the right”.

The Jewish community was seen as never having wanted the pro-Palestine Corbyn in power, Wagner adds, “so it needed a broad communal church [to tackle left-wing antisemitism] which is why I worked with the CAA to get the Equality and Human Rights Commission (EHRC) involved. It needed an organisation on the left to show what was going on. It couldn’t come from the Conservatives, the ZF, or even the Board since all were seen as right-wing. It had to be from the left otherwise they’d always feel it was political. That’s why the Corbynite left hate me – they couldn’t say that about me. I’d headed a socialist youth movement and lived in a socialist commune, unlike most of them.”

A splintered left

Hannah Weisfeld says Yachad’s membership “remains strong”, but that “what we’re seeing now is a whole new generation who don’t have the patience to play nice in this ridiculous community. Take Na’amod. Many began with us, but they got fed up with the community, the direction it took, the impact Corbyn had on the way we talked about Israel. That’s why we’re seeing a further fracturing now. There’s a whole gang of them who think the Board is a racist joke and if you work with them then you’re basically racist.

“They think the work we do, trying to actively change [Zionist organisations like the Board and the ZF] from within, is a waste of time and possibly counter-productive. So, there’s now a splintering of the progressive Jewish left. I don’t think it’s severe, but it exists.”

Few disagree with that, and others pick up the theme. Kahn-Harris says Boris Johnson’s 2019 election win was “heart-breaking” to young left-wing Jews yearning for a socialist government. That led to a realignment, he says. “The young Jewish left suddenly became more antagonistic to the Labour right. For them, the Jewish community’s possible part in the election of Johnson was very difficult to deal with.”

Kahn-Harris adds: “A distinctively different Jewish left has now emerged. Groups like Na’amod and Jewdas are less avowedly secular than the Jewish socialist left, more connected into Jewish communal life. They also have a disproportionately high number of engaged Jews. Many are machers [organisers]. So, in the Reform, Masorti and Liberal communities, they have a disproportionate influence.”

Yet while the left of Jewish politics may well have splintered, this does not mean that the Jewish left and centre are not capable of “getting their act together when it matters,” advises one well-placed Jewish leader. “I don’t think it’s split,” they say. “At the recent Board election, the left and the centre didn’t put a candidate up against [President] Marie [van der Zyl], which would have let the right in. When push comes to shove, they’re sensible, because the right is knocking at the door.”

Poles apart

Yachad director Weisfeld stridently argues that Israel – through its policies – has “destroyed” the British Jewish community. “For me, the Jewish people cannot survive and thrive with a nation-state doing what it’s doing in the name of the Jewish people,” she says. “For others, that’s the only way the Jewish people can survive. Where’s the common ground there? I think Israel is destroying – and I don’t say this with any glee – I think what Israel’s done to the Jewish community is to destroy it.”

Rabbi Andrew Shaw, chief executive of Mizrachi UK, says two decades ago the Jewish left and right disagreed on Israel “but we all loved Israel and knew who our enemies were. We’d debate the two-state solution but were united on those central points. Today, the Jewish left have become almost self-hating”. Expressing “concern about youngsters today,” he adds: “The political left has turned them anti-Israel. I wasn’t surprised by Kaddish for Gaza. I saw it coming.”

Rabbi Janner-Klausner, meanwhile, says that, on Israel, “the right has moved further to the right and the left has moved further to the left”, a sentiment few disagree with. “It’s a reaction to what’s happening out there,” she says. “When you have an occupation, whatever happens is going to be corrosive and terrible.”

Charney agrees only to a degree. “The left has gone more left. I don’t think the right has gone more right,” he says. Shaw agrees, seeing it as part of a bigger picture. “Across the world, the left has been radicalised,” he says. “It’s very anti-Israel, very antisemitic, very poisonous. The Jewish left has just absorbed that and connected to it, shockingly. The left has become synonymous with an extreme anti-Israel view.”

The vanishing centre

What would a Jewish political centrist believe today? How would you describe the Jewish political centre-ground in 2021? Who are the centrists? Do they even exist?

That most British Jews support Israel is rarely disputed. Beyond that, things get tricky, and optimism fades. “I don’t think the ability to find a communal centre ground on Israel is shrinking,” says Yachad’s Weisfeld. “I think it’s gone. It’s literally impossible. What would the centre be? People caring deeply about the future of Jews? That’s about where it ends.”

Asking a senior and highly involved figure where the political middle ground is today, the answer is stark: “There isn’t any.” Antisemitism pushes people to the right, the left push further left, leaving “virtually no centre ground.”

Does that make the Jewish community unleadable? “Almost. To find consensus in it, a leader has to be of differing persuasions, such as socially liberal but right-wing on Israel, which is what we’ve got now [in reference to Board president Marie van der Zyl]. Is that what you’d call ‘centrist’ today? Probably.”

Cohen, whose social media profile has steadily grown, says this vanishing centre comes down, in part, to the way we interact and communicate online. “Centrist positions are less impactful than non-centrist positions,” he says. “Look at Brexit, Trump, Israel. If I put out a positive video, it’s far less likely to get shared by lots of people than something negative inducing fear.Similarly, activists create content and engage in actions that they know will create stories and get a reaction. The more support it gets from their own side, and the more negative attention it gets from the other side.”

The latest battleground

At the Board, those who believe that deputies are waging war between ‘left’ and ‘right’ camps say the next big battle is underway, and depending on who wins it later this month, several sources say it could presage a communal lurch to the right in three years’ time.

That “battle” is for the vice-chairmanship of the Board’s all-important Defence Division, which will be decided in the coming days and weeks. It is the position from which all recent Board presidents have emerged. “The right have their man – Jonathan Neumann – and they’re desperate for him to win it, so that he becomes the likely winner of the presidency in 2024,” says one well-placed source. The other candidates are Ephraim Borowski from Scotland, and James Harris, a centre-right former Jewish student leader.

Nominations for the vice-chair of the Defence Division closed on Monday. Two weeks earlier, 40 people had applied for the division’s 16 available positions. “It’s virtually unheard of,” says someone with a close view of proceedings. “And it shows exactly what’s going on.”

• Don’t miss part two of this special report, entitled Divided Over Division, in the 26 August edition

Thank you for helping to make Jewish News the leading source of news and opinion for the UK Jewish community. Today we're asking for your invaluable help to continue putting our community first in everything we do.

For as little as £5 a month you can help sustain the vital work we do in celebrating and standing up for Jewish life in Britain.

Jewish News holds our community together and keeps us connected. Like a synagogue, it’s where people turn to feel part of something bigger. It also proudly shows the rest of Britain the vibrancy and rich culture of modern Jewish life.

You can make a quick and easy one-off or monthly contribution of £5, £10, £20 or any other sum you’re comfortable with.

100% of your donation will help us continue celebrating our community, in all its dynamic diversity...

Engaging

Being a community platform means so much more than producing a newspaper and website. One of our proudest roles is media partnering with our invaluable charities to amplify the outstanding work they do to help us all.

Celebrating

There’s no shortage of oys in the world but Jewish News takes every opportunity to celebrate the joys too, through projects like Night of Heroes, 40 Under 40 and other compelling countdowns that make the community kvell with pride.

Pioneering

In the first collaboration between media outlets from different faiths, Jewish News worked with British Muslim TV and Church Times to produce a list of young activists leading the way on interfaith understanding.

Campaigning

Royal Mail issued a stamp honouring Holocaust hero Sir Nicholas Winton after a Jewish News campaign attracted more than 100,000 backers. Jewish Newsalso produces special editions of the paper highlighting pressing issues including mental health and Holocaust remembrance.

Easy access

In an age when news is readily accessible, Jewish News provides high-quality content free online and offline, removing any financial barriers to connecting people.

Voice of our community to wider society

The Jewish News team regularly appears on TV, radio and on the pages of the national press to comment on stories about the Jewish community. Easy access to the paper on the streets of London also means Jewish News provides an invaluable window into the community for the country at large.

We hope you agree all this is worth preserving.

- News

- News Features

- Jewish Council for Racial Equality (JCORE)

- Board of Deputies

- Portsmouth and Southsea Hebrew Congregation

- kaddish for Gaza

- International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance (IHRA) definition of antisemitism

- Joseph Cohen

- Campaign Against Antisemitism

- Israel Advocacy Movement

- Zalmi Unsdorfer

- Keith Kahn-Harris

- Laura Janner-Klausner

- Labour Against Antisemitism

- Gnasher Jew

- Adam Wagner

- Campaign Against Antisemitism (CAA)

- Equality and Human Rights Commission (EHRC)

- Hannah Weisfeld

- Yachad

- Na’amod

- Jewdas

-

By Brigit Grant

-

By Laurent Vaughan - Senior Associate (Bishop & Sewell Solicitors)

-

By Laurent Vaughan - Senior Associate (Bishop & Sewell Solicitors)

-

By Laurent Vaughan - Senior Associate (Bishop & Sewell Solicitors)

-

By Laurent Vaughan - Senior Associate (Bishop & Sewell Solicitors)