OPINION – Rob Rinder: We must tell our children and our children’s children

Robert Rinder reflects on his grandfather’s experience and explores the impact of the Holocaust on the second and third generations in his upcoming two-part documentary

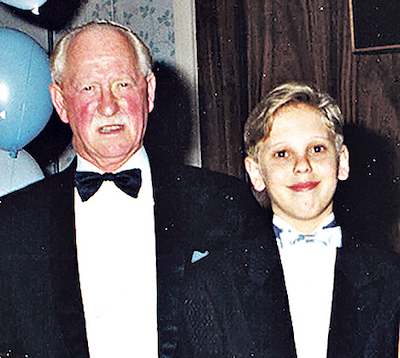

I was always aware my grandfather, Morris Malinicky, was a Holocaust survivor from Piatrakow, the same town as his friend, Sir Ben Helfgott.

While we knew about the Holocaust, like so many of his generation we were only told the dark outlines of his story and not the colouring in of the details.

There’s never a single moment when a survivor sits down and tells a story from beginning to end. Instead it emerges during a series of interactions, a jigsaw puzzle you have to piece together to form an understanding of what happened.

Get The Jewish News Daily Edition by email and never miss our top stories Free Sign Up

I remember him being explosive around food, insisting we finished our meals, and then in later years when he passed away, we discovered little food parcels dotted about his home, at the back of wardrobes and in drawers, despite him being considerably comfortable.

I understood then, how in ensuring we were always well-fed, he was expressing his love.

There were other strange vignettes, moments that felt dislocated from anything especially relevant from my childish understanding. I remember him saying never to push yourself forward, before learning about his time in Schlieben, one of the sub camps at Buchenwald, where Ben was also sent.

There were three works, A, B and C and he noticed that A looked easier, being located indoors away from the biting cold.

Having been selected for work C, which looked much more arduous, he pushed himself quietly into A’s queue, where he was caught and beaten by a Nazi guard. But in the event, Work A was substantially more dangerous, for here they worked with toxic chemicals, reducing life expectancy to just three months.

He would tell this story, a fleeting story sandwiched between the most banal, day-to-day existence, in-between telling jokes or whatever else and it would just emerge, as if it needed to be told and couldn’t be contained.

All these incoherent tales and moments were explained away by the whispers of him being a survivor and what he’s been through.

That in itself was a complicated thing, because you couldn’t talk to him, you couldn’t drive the conversation. You couldn’t be upset

with him, because of what he’d been through. There was an unequivocal barrier and one which was much more profoundly, emotionally policed for my mum and auntie than for me as a third generation child.

My first real glimpse into my grandfather’s life before the Holocaust came in 1998, when I travelled with him to Piotrków Trybunalski.

We visited a place he once lived and there was this extraordinary moment where he recognised a woman there. She looked at him and he touched her. They didn’t say anything, but in the few seconds of their connection, there was a kind of a sense of the human divine.

She was the only survivor of that building and her family had been the Shabbos goys. As a child, she played with my grandfather. There he was now, standing with his two grandsons – and she had no idea he had survived.

Even then, as a young man, I wasn’t able to really appreciate the significance of this moment, but what I did understand was more about his Polish identity. That he was rooted in this land of distance, that there had been a Jewish community there, a richness and history that was there no longer.

A couple of years ago, I was asked to go on BBC One’s Who Do You Think You Are? and as we began, I set out thinking I knew much about my grandfather, but I was totally wrong.

There were many profound things that happened, from the unbelievable coincidence of sitting in my grandfather’s flat on the day of his 95th birthday, to discovering that the grandfather of Netanel, the historian helping me, had owned the building and been one of my grandfather’s best friends.

But there was no greater gift to my family than when Netanel found a book about life in Pietrokow, which included whole sentences about my family. That my great-grandfather, Elimelech, was a man who dotted about the place, a man small in stature, but high in hopes. That my grandfather’s sisters were good in school and enjoyed performing.

Those words breathed life into them, gave them neshama, simply by reading the words of somebody who had a memory of them.

My episode, which helped the series earn a BAFTA, was watched by seven million people and became the highest rated programme about the Holocaust for many years.

There wasn’t a peep of antisemitism on social media and its success had nothing to do with the power of my celebrity. There were infinitely more famous people in the series. It was all to do with the story itself and how beautifully it was told.

In the wake of the show’s success, I’m working with on a new two-part documentary, My Family, The Holocaust and Me, which follows the stories of second generation families.

All, apart from my own, are located in Western Europe, which was really important.

For a long time, we have come to understand the Holocaust as an Eastern European phenomenon, but it was in Germany where it fermented in the first place.

This was not some cultural backwater. The Holocaust began in the most advanced political society in the world, teaching us we should never be complacent about democracy.

We also wanted to explore the impact of trauma on the second generation, many of whom feel imbued with a quiet sense of responsibility to tell the stories of their parents, but who have often lived lives steeped in inherited trauma.

And lastly we wanted to ensure instances of the most profound heroism were not forgotten.

We learnt about Marianne Cohn, who risked her life rescuing children by taking them across the Alps from southern France into Switzerland, and a man named Henk, who hid the grandfather of cellist Natalie Clein and her sister, Emmerdale actress Louisa Clein.

Telling the stories of these heroes is important, because if people could choose, they would surely wish to be on the side of the morally righteous, those who made determined, death-defying choices to do the right thing.

For second generation survivors there is never a sense of closure, nor will there ever be. It exists within you and affects the very prism through which you see the world.

That was certainly true in my case and for my mother, Angela, who has taken over from Ben as president of the 45 Aid Society.

In making this programme, I felt she was finally ready to go to Treblinka, to say Kaddish for our family members.

The last known survivor of this incongruous place, Samuel Willenberg, died in 2016.

As we were about to begin, director David Vincent suddenly told us there was in fact still another survivor, a man named Leon Rytz, from Gothenburg in Sweden.

“He’s never been back here and he didn’t want to come,” said David. “But having seen your mum on Who Do You Think You Are? he decided he had to be here today.”

As I turned round, I caught sight of this blue-eyed man and said, “Leon, tell me what happened here?” He simply put his head on his shoulder and sobbed.

Opening her small siddur, my mum began Kaddish and as I was about to say the names of my family, to sing them into the air, Leon said: “Robert, this is for Kol Yisroel, for all the Jewish people.”

It was the most profound moment of my life. Indeed, it is for all the Jewish people that we, the second and third generations, must ensure their stories continue to be heard.

That their memories are never allowed to fade into a quiet whisper.

• My Family, The Holocaust and Me will be aired later this year

Thank you for helping to make Jewish News the leading source of news and opinion for the UK Jewish community. Today we're asking for your invaluable help to continue putting our community first in everything we do.

For as little as £5 a month you can help sustain the vital work we do in celebrating and standing up for Jewish life in Britain.

Jewish News holds our community together and keeps us connected. Like a synagogue, it’s where people turn to feel part of something bigger. It also proudly shows the rest of Britain the vibrancy and rich culture of modern Jewish life.

You can make a quick and easy one-off or monthly contribution of £5, £10, £20 or any other sum you’re comfortable with.

100% of your donation will help us continue celebrating our community, in all its dynamic diversity...

Engaging

Being a community platform means so much more than producing a newspaper and website. One of our proudest roles is media partnering with our invaluable charities to amplify the outstanding work they do to help us all.

Celebrating

There’s no shortage of oys in the world but Jewish News takes every opportunity to celebrate the joys too, through projects like Night of Heroes, 40 Under 40 and other compelling countdowns that make the community kvell with pride.

Pioneering

In the first collaboration between media outlets from different faiths, Jewish News worked with British Muslim TV and Church Times to produce a list of young activists leading the way on interfaith understanding.

Campaigning

Royal Mail issued a stamp honouring Holocaust hero Sir Nicholas Winton after a Jewish News campaign attracted more than 100,000 backers. Jewish Newsalso produces special editions of the paper highlighting pressing issues including mental health and Holocaust remembrance.

Easy access

In an age when news is readily accessible, Jewish News provides high-quality content free online and offline, removing any financial barriers to connecting people.

Voice of our community to wider society

The Jewish News team regularly appears on TV, radio and on the pages of the national press to comment on stories about the Jewish community. Easy access to the paper on the streets of London also means Jewish News provides an invaluable window into the community for the country at large.

We hope you agree all this is worth preserving.

-

By Brigit Grant

-

By Laurent Vaughan - Senior Associate (Bishop & Sewell Solicitors)

-

By Laurent Vaughan - Senior Associate (Bishop & Sewell Solicitors)

-

By Laurent Vaughan - Senior Associate (Bishop & Sewell Solicitors)

-

By Laurent Vaughan - Senior Associate (Bishop & Sewell Solicitors)