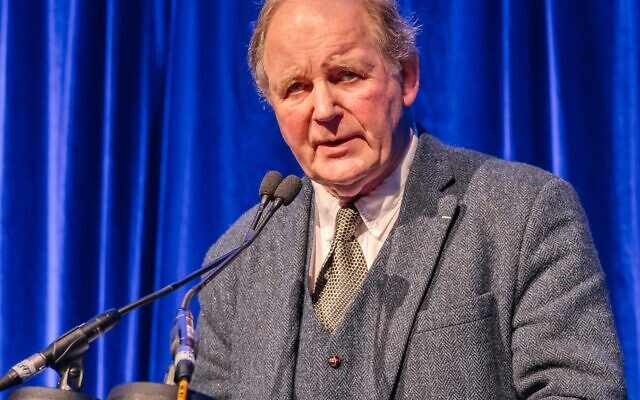

Sir Michael Morpurgo: ‘Anne Frank’s Diary was her living testimony. And it lives on today’

Beloved author of War Horse speaks movingly of the profound impact the Holocaust diarist had on his life

I am a war baby, born on 5th of October 1943. Anne Frank probably died on 31st of March 1945. We shared this world for only a few months.

Whilst she was hiding away in an attic with family and friends from the Nazis, while she and they were finally being betrayed and taken away to Bergen Belsen concentration camp to be murdered in the Holocaust like millions of others, I was being looked after in my grandparents’ comfortable house in Radlett, outside London, with a garden, surrounded by family, under threat of the war of course, but I knew nothing of that. I knew nothing of the concentration camps either. I did not know about the evil that men do, that sadly does live after them, if we allow it to.

When Hitler sent over the V2 rockets to do their indiscriminate killing, I was evacuated 300 miles north, well out of range. During my early childhood, the war, the history and the myth of it, was ever present, from the bombsites we played in – playing war games mostly – from the photo of my Uncle Pieter on the mantelpiece who had been killed in the RAF in 1941, aged 21, from the soldier with one leg often begging on the street corner near my school, I thought of war as a sort of killing game.

It took me a while to realise that it wasn’t a game, that war destroyed houses, flesh and uncles. BuI I think I only began to comprehend the depth of the tragedy of it when I saw my mother crying over the death of Uncle Pieter, her beloved brother. I caught her sadness, I think, and came to miss the uncle I never knew, and so began to understand the pity of war very young.

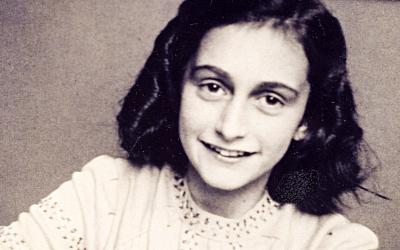

But I must have been eleven or twelve when I first knew anything of Anne Frank or the Holocaust. My family knew about it of course, but never told me. Like millions of my generation and in the generations to follow, I learnt about it through reading Anne Frank’s Diary. Her face was on the opening page looking out at me.

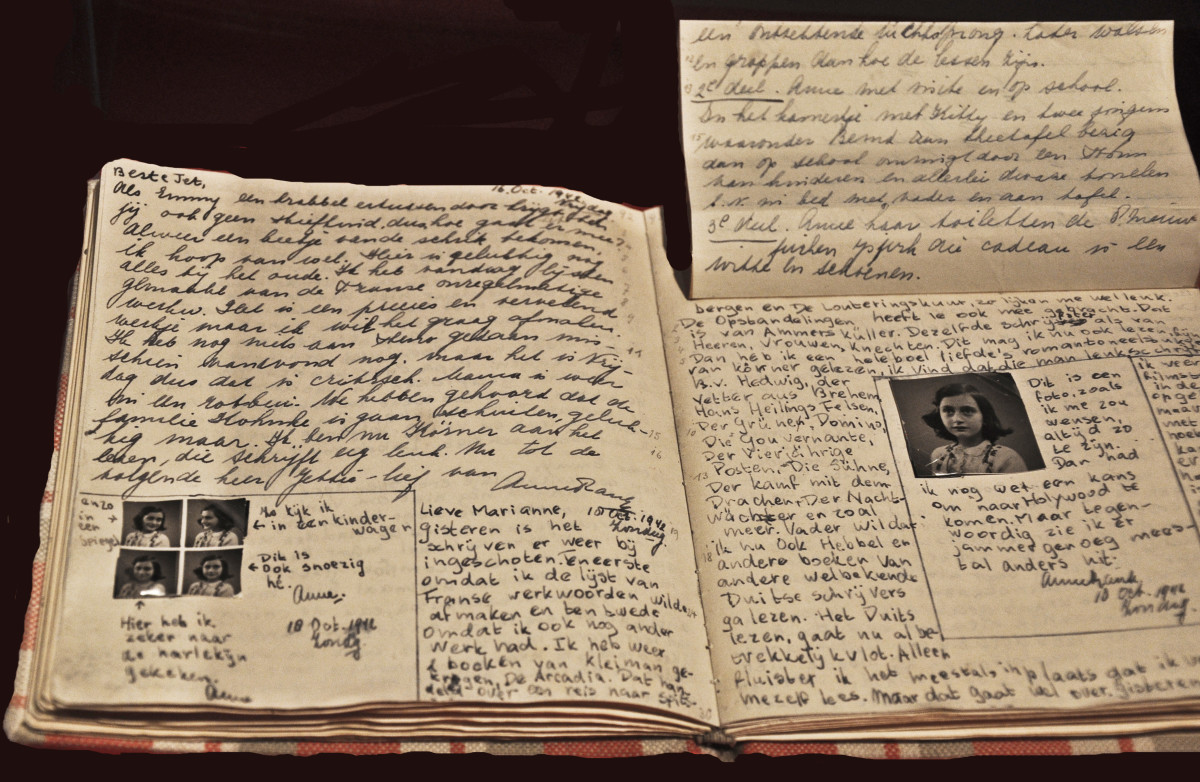

She wrote directly to me, confiding in me, telling me how it was to be her, how she was enduring her imprisonment in her attic in Amsterdam, the tedium, the frustration, the dread, the anger, the memories, the friends and relations, the hope, the longing to be free again, for liberation to come. It was her living testimony. And it lives on today.

The last page of her diary is the last we hear of her. She is simply not there any more. We knew before we ever read it that she had died, that these were to be her last words. Once read it is never forgotten.

It was of course not written to be read by others. She did not know that this was to be her testament, the most personal insight into the life of a spirited but ordinary girl whose name and face was one day to be famous all over the world, was to represent for so many all the wickedness and the waste, horror, the tragedy, shame and pity of the Holocaust.

For ever afterwards, her life and her death has given me, us, some way of beginning to understand the Holocaust. She was the one of the 6 million we all came to know. Her short life and death remind us of man’s inhumanity to man, of the depth of cruelty and depravity we are capable of, of the power of prejudice so easily aroused to fuel hate.

For ever afterwards, her life and her death has given me, us, some way of beginning to understand the Holocaust. She was the one of the 6 million we all came to know. Her short life and death remind us of man’s inhumanity to man, of the depth of cruelty and depravity we are capable of, of the power of prejudice so easily aroused to fuel hate.

But Anne also gives us hope, the hope she had, that all can be well again, if we make it well. Her words, her suffering, her death, give us the determination to right the wrongs of antisemitism and prejudice of all kinds, to create a world where kindness, empathy and understanding rule.

Because of Anne, scribbling away up in her crowded attic room, I have had her story and her fate, and the iniquitous and vile Holocaust in my head for much of my life. It’s no accident then that I have written my own stories about it, stories like The Mozart Question.

This story and so many others were, I feel sure, originally inspired in part by a family friend I had grown up with as a child and known well – Mac, we called him, Ian Mcloed. He was amongst the very first British soldiers in the Royal Army Medical Corps to enter the concentration camp at Bergen Belsen, on the 15th of April 1945, where Ann Frank had died just a week or two before. A young man, a teenager at the time, Mac witnessed the horror of Belsen with his own eyes, and suffered from the effects of that terrible experience all his life.

His life, his being there at the liberation of Bergen Belsen, was the first of many personal connections to the Holocaust that have echoed through my own life, in so many ways.

For instance, growing up I was unaware of the Jewish origins of my step family. My birth name is Bridge, my father an actor, Tony Van Bridge, but my mother left him in 1946, to marry one Jack Morpurgo, from a Jewish family that emigrated to London in the early 20th century. So aged 2, I became a Morpurgo. It is a Jewish name from northern Italy, well respected there. Many many Morpurgos I later discovered had died in the camps.

And there was the violin. Go to the Violins of Hope Museum in Tel Aviv, and you will find amongst all the violins played in the concentration camps, the Morpurgo violin. It belonged to one Galtiero Morpurgo, a survivor of the camps, who was still playing the violin until he died aged 97. His family donated his violin to the museum.

Strangely, I did not know about this Morpurgo violin when, twenty years before I wrote a story of mine I called The Mozart Question. It is to me perhaps my most important book. By this time I had of course read Primo Levi, I had known and become a good friend with Judith Kerr, fellow children’s writer, and author of Hitler Stole Pink Rabbit, based on her family’s escape from Germany in 1933.

And I had discovered that a great teacher of mine, Paul Pollock, who had taught me classics at school, had been a child on the last train of Jewish children to leave Nazi occupied Prague in 1939, one of hundreds saved from the Holocaust by the wonderful Nicholas Winton. Mr Pollock was a devoted and eccentric teacher known and much respected for his extraordinary intelligence and famous for his withering remarks, his cutting barbs.

His barber was once overheard asking him: “And how would you like your hair cut today, sir?” “In silence,” Mr Pollock replied. He died only six months ago, at over a hundred years old. And we never realised when we were boys what he had been through, how he had no family but us. They’d all gone. He was alone in the world.

I have his story and Mac’s story and others in my mind as I am talking to you today. They connect me to the Holocaust. They all lived on. But Ann Frank was the first and most important of these connections, and she did not survive.

I have his story and Mac’s story and others in my mind as I am talking to you today. They connect me to the Holocaust. They all lived on. But Ann Frank was the first and most important of these connections, and she did not survive.

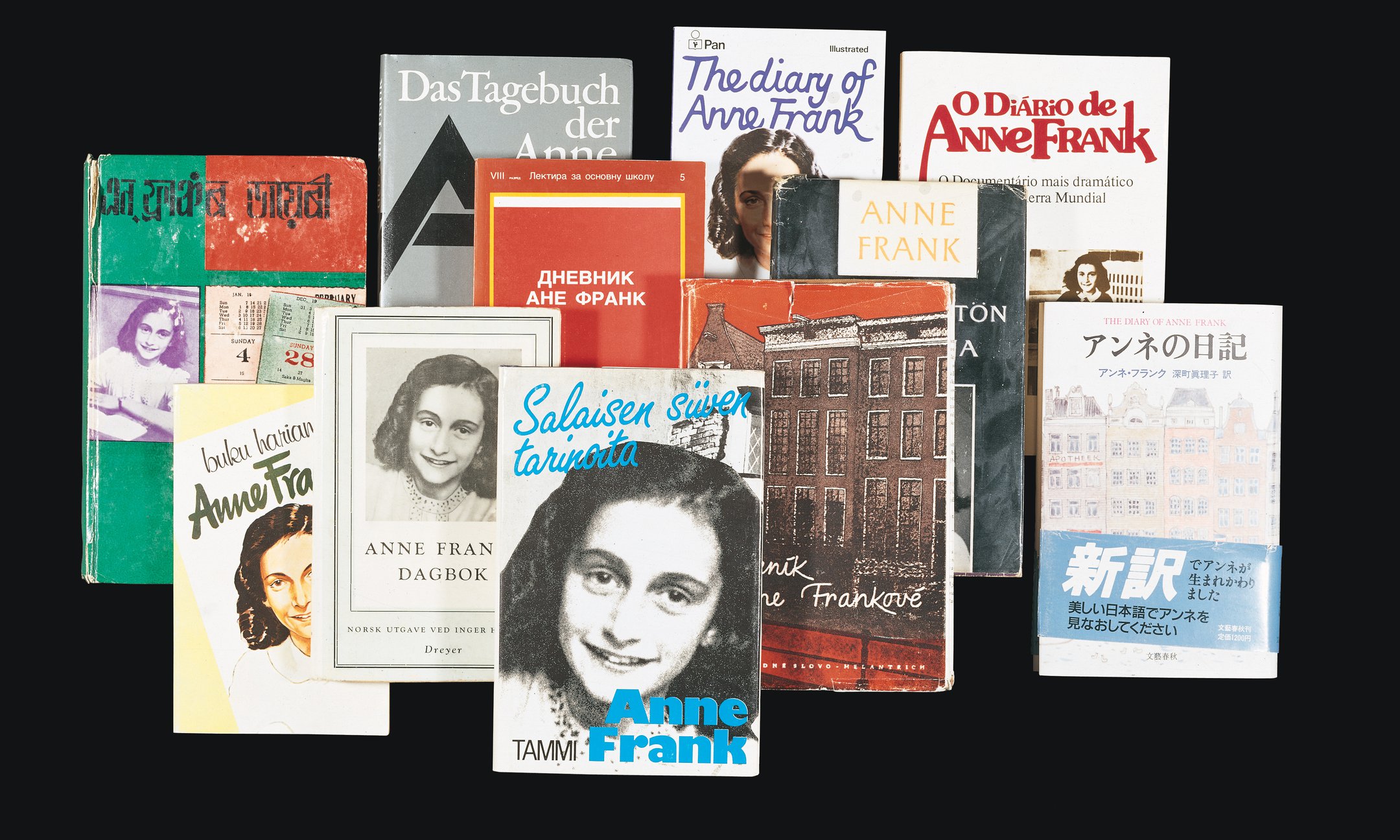

But the diary she wrote hiding away in her attic room in Amsterdam is for so many millions around the world the first and most lasting connection to those times, to those lost millions of the Holocaust, each of whom was a living breathing precious human being, a daughter, a son, a mother, a father.

It is primarily then because of Anne’s enduring story, that I am here, honoured to be be talking to you today. Like her, I’m a storymaker too, a writer – and what books she might have written had she lived, can you imagine? I write under my given name.

I am here in part because of my Morpurgo name. And I am here because of Mac, Ian Mcloed, the medical orderly at Bergen Belsen, whose story I knew growing up; and it is because of the discovery of the story of the Morpurgo violin in Tel Aviv, and of my friendship with Paul Pollock, my teacher, and dear Judith Kerr – two of those who escaped the Holocaust and came to live and do so much good for us in their adopted country. For me all these people and all these circumstances conspired to bring me here today.

It is because of all this, because of them and all they lived through, that I know as we all do that prejudice has to be fought, that prejudice is a disease that can so easily become an epidemic of hate, a pandemic that can overwhelm us, if we ignore it or look the other way. It is a pandemic against which we have to be vigilant, and that has to be confronted. Historical awareness, and stories can help in this struggle.

I’m firmly convinced that unless we know and remain aware of where prejudice can and does lead, unless we know the history of the Holocaust, then it can happen again, again and again. And I’m also convinced that it is stories that can keep us vigilant, that all of us growing up have to be made aware, generation after generation.

That’s why I am with you here today, why I have written my stories of those times, of war and oppression, of occupation, and of the Holocaust in particular in Waiting for Anya and my story of a violin in the concentration camps, The Mozart Question, in which the power and beauty of violin music can and does overcome brutality and evil. We owe it to them, to those who died in the Holocaust, to Ann Frank, and to those who survived, to go on telling the story.

And, we owe it to them surely to do more, to seek peace and reconciliation, to create the kind of world I discovered on my visit to Israel and Gaza, ten or so years ago, with Save the Children. I was taken to a village and to a school called Neve Shalom, Oasis of Peace, Wahat A Salam, the only place, so far as I know, where Jew and Arab go to school together.

We made kites together, flew kites together, made music together. Such a place, such a spirit, such children and families, and teachers will put the world to rights. There was hope there, there was peace there. Hope springs eternal, and hope brings peace.

Let there be peace.

Speech from Anne Frank Trust UK annual lunch reprinted in full with the author’s permission.

- Sir Michael Morpurgo, author, poet and former children’s laureate

Thank you for helping to make Jewish News the leading source of news and opinion for the UK Jewish community. Today we're asking for your invaluable help to continue putting our community first in everything we do.

For as little as £5 a month you can help sustain the vital work we do in celebrating and standing up for Jewish life in Britain.

Jewish News holds our community together and keeps us connected. Like a synagogue, it’s where people turn to feel part of something bigger. It also proudly shows the rest of Britain the vibrancy and rich culture of modern Jewish life.

You can make a quick and easy one-off or monthly contribution of £5, £10, £20 or any other sum you’re comfortable with.

100% of your donation will help us continue celebrating our community, in all its dynamic diversity...

Engaging

Being a community platform means so much more than producing a newspaper and website. One of our proudest roles is media partnering with our invaluable charities to amplify the outstanding work they do to help us all.

Celebrating

There’s no shortage of oys in the world but Jewish News takes every opportunity to celebrate the joys too, through projects like Night of Heroes, 40 Under 40 and other compelling countdowns that make the community kvell with pride.

Pioneering

In the first collaboration between media outlets from different faiths, Jewish News worked with British Muslim TV and Church Times to produce a list of young activists leading the way on interfaith understanding.

Campaigning

Royal Mail issued a stamp honouring Holocaust hero Sir Nicholas Winton after a Jewish News campaign attracted more than 100,000 backers. Jewish Newsalso produces special editions of the paper highlighting pressing issues including mental health and Holocaust remembrance.

Easy access

In an age when news is readily accessible, Jewish News provides high-quality content free online and offline, removing any financial barriers to connecting people.

Voice of our community to wider society

The Jewish News team regularly appears on TV, radio and on the pages of the national press to comment on stories about the Jewish community. Easy access to the paper on the streets of London also means Jewish News provides an invaluable window into the community for the country at large.

We hope you agree all this is worth preserving.