‘Startling and sobering’ Auschwitz exhibition

The exhibition everyone is talking about has a strong message and lasting impact

Naomi is a freelance features writer

Mournful string music weaves the melancholy mood as you enter the Seeing Auschwitz exhibition in South Kensington. Open since October, it comprises a collection of 100 photographs of the camp that have survived to the present day, with an audioguide that includes testimonies from survivors.

This might sound like a sterile overview, but the 60-75 minute experience is anything but. The images, shot by perpetrators, victims and liberators are presented not just as proof of the mass genocide but as a startling, sobering glimpse into the precious human lives lost. The vast collection of images come from varying sources including aerial allied pictures of the camps, documentation of the deportation process and living within Auschwitz as well as insight into life before the camps.

Lead curator and one of the world’s leading experts on the Holocaust, Paul Salmons says: “They look like faithful portraits of an instant, but these photographs are not neutral sources at all: we are looking at a piece of reality but seen from the Nazi perspective. It is necessary to stop and analyze them to really see what each image truly reveals, not only about the place and the moment, but also about their own authors, the people portrayed, and even about ourselves as viewers”.

The images are deliberately blown up, so you can examine each facet, almost walking closely along with the victims. It is simple to navigate, with engrossing audio accompanying each exhibit. I soon become immersed in the stories each picture and its commentary paints.

As a third generation descendant of Holocaust survivors the subject was ingrained in me growing up. I remember poring over the memorial book my late great aunt penned for our family, staring at the pictures of the sweet little babies who later gasped and choked on deadly gas, the many cousins my mum still laments she never got to meet. She grew up with no extended family besides her mother’s brother who escaped to Britain on Kindertransport.

I remember hearing how my great aunt was a healthy young woman when she was sent to Auschwitz. Typhus and disease ate away at her face and she had to have an emergency skin graft after liberation with no anaesthetic. They just cut into her face to remove the infection and fever.

I stand in front of the blown-up image of the arrival of Hungarian Jews to Auschwitz, scrutinising it to see if I could glimpse any familial faces. The confusion and terror of mothers and children are palpable. I remember reading about how Nazis would shoot pregnant women in their stomachs for sport and smash babies heads against walls in front of their mothers, who they then shot as they fainted in shock and grief. In the images there are babies and toddlers sitting in the birch grove with their siblings and mothers. One proffers a flower he has picked to his or her brother. The caption says they are awaiting the gas chambers, and this makes me balk.

Another section of the exhibition shows the Nazis at play, relaxing and laughing at a summer house. There is a group picture of Nazi officers enjoying some live music. One of the smiling faces is striking, handsome even. It’s Mengele, the savage ‘doctor of death’ as he was called by prisoners.

I remember my mum telling me how she would listen in when my grandmother went to visit her friend Irene, hearing her quiet muffled sobs and hushed whispers about how she was cruelly experimented on by Mengele, and how she could never have children of her own.

I remember the stories my grandmother told about her childhood in Germany, how she stood up to the Gestapo at age 17, demanding they release her father who served in WW1. He got sent to a death camp anyway.

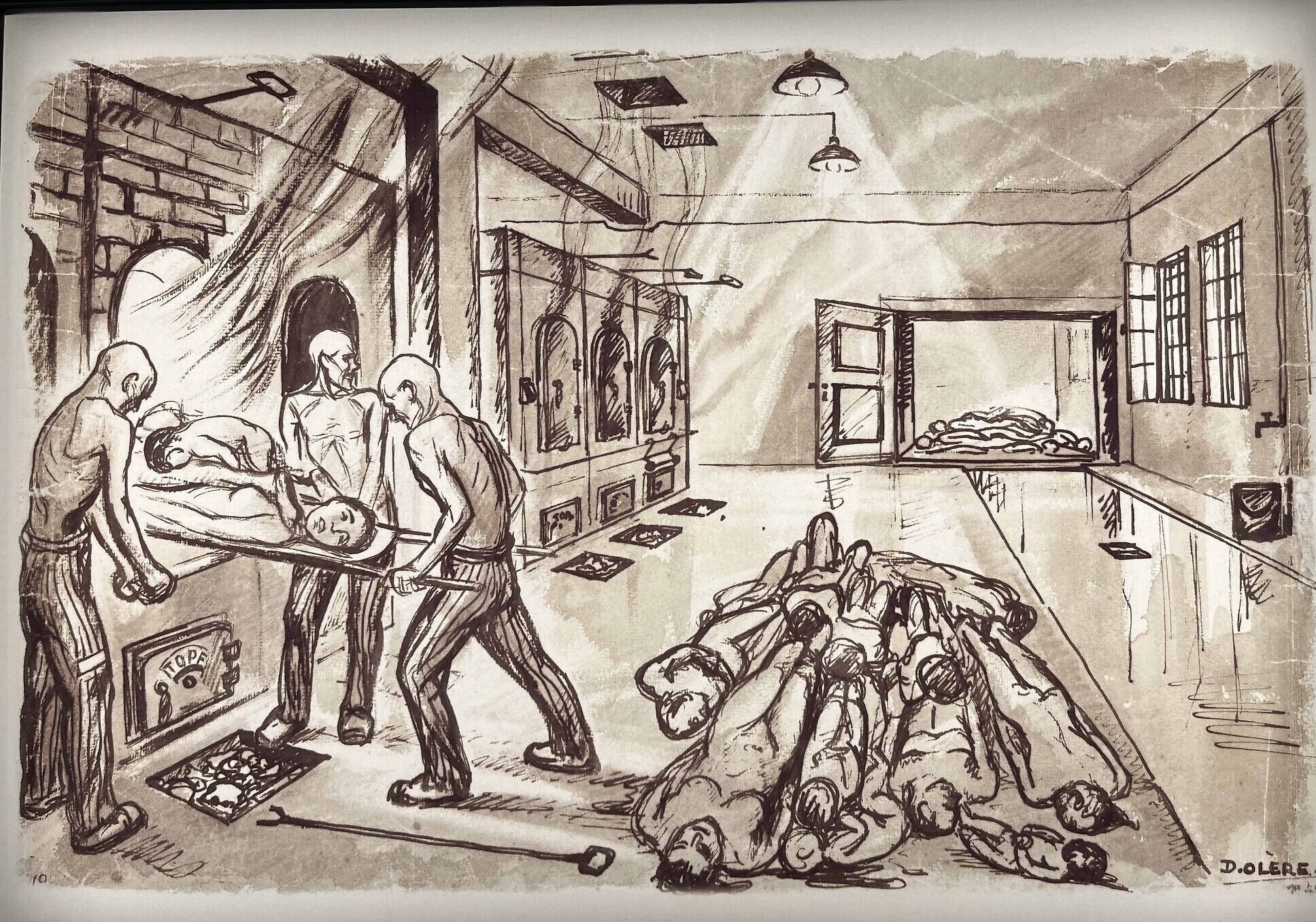

The section that stayed with me most was the one detailing the Sonderkommandos – ‘special command unit’. These were groups of Jewish prisoners forced to perform a variety of duties in the gas chambers and crematoria of the Nazi camp system.

The section that stayed with me most was the one detailing the Sonderkommandos – ‘special command unit’. These were groups of Jewish prisoners forced to perform a variety of duties in the gas chambers and crematoria of the Nazi camp system.

This was particularly raw for me, as I grew up hearing about my great uncle, Mordechai (Martin) who was a teen, a yeshiva student when he was ordered to move corpses into the ovens in Auschwitz once the gas chamber had done its work. Including Jews he knew and loved. Potentially his own nieces and nephews. Friends and rabbis.

The Nazis usually killed those who did this work to hide evidence of their crimes, but Martin and some other workers heard of a transport that would leave Auschwitz one morning. The night before, they dug a hole under the barbed wire fence and joined the transport that took them to Matthausen concentration camp. After the war, he made contact from Prague with my great aunt and seemed to be in a terrible state emotionally and physically – he had tuberculosis from the camps. He told her that he was leaving Czechoslavakia in 1947 for fear that Russia was going to take over the country. He sent her an address in Windsheim, Germany, his planned destination. The letter that he promised would come with some personal papers never arrived and he was never heard of at that address. He just vanished into thin air.

We will never know what happened to him. Did he commit suicide, driven mad by the anguish of what he was forced to do by the Nazis? Did he die of TB? Was he killed for those personal papers that were most likely coveted by others seeking refuge elsewhere? He was just a teenager.

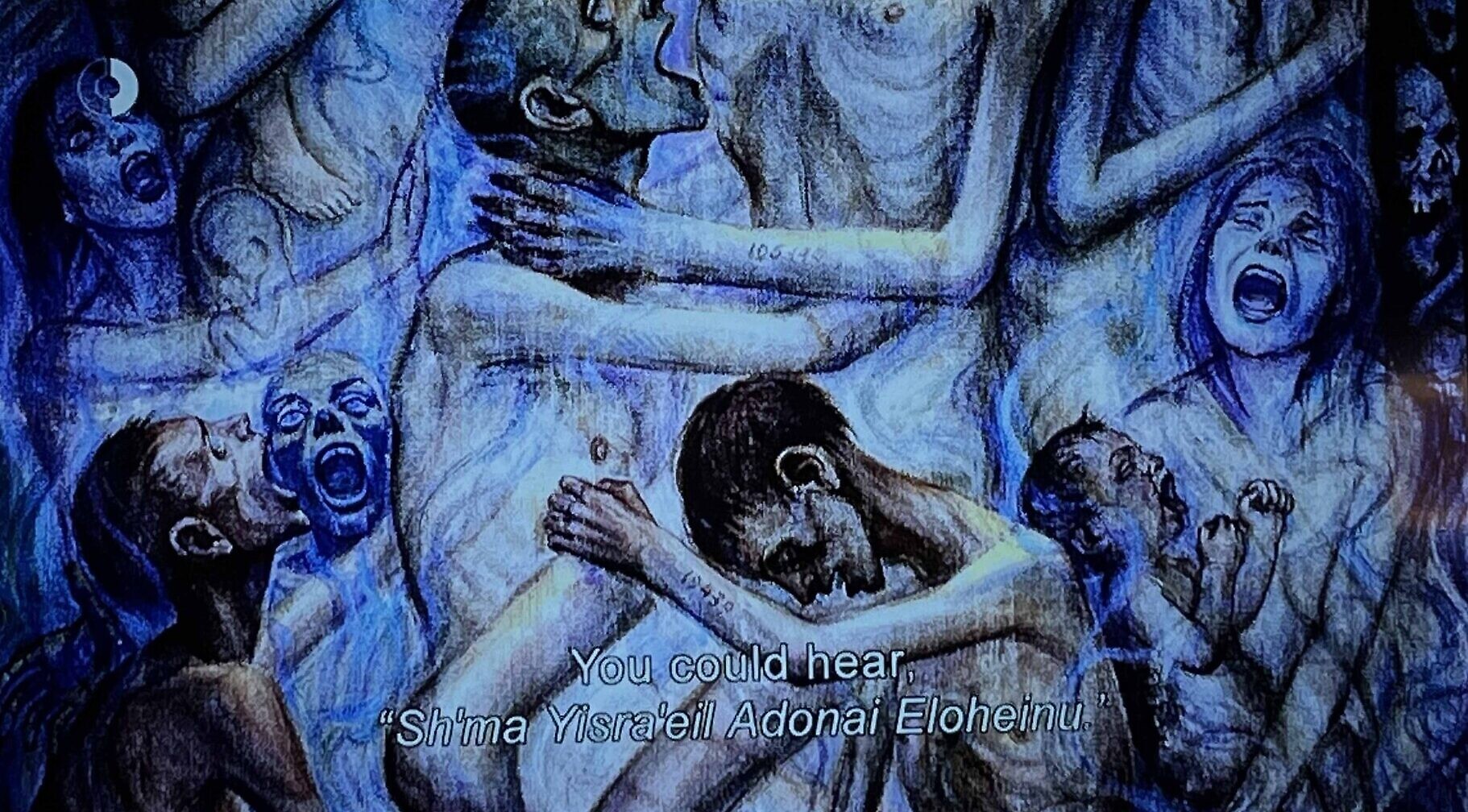

There are mounted screens with survivors who were also teenagers at the time forced to do this macabre work, speaking about their experience. I sit and watch, and the survivor on the screen recounts how there was a rabbi, whose mind eventually went because of the sheer trauma and horror of it all. He took it upon himself to search for the dead babies amongst the pile of mangled bodies, recited the Viduy ‘confession’ to be recited before one departs from this world, kissed each on the face and threw them in the ovens. After the war, he could not bear the sound of a baby crying.

Something inside me breaks and tears are streaming down my face. This and other stories were new, horrific anecdotes I hadn’t heard before. I was struck how uncompromising the graphic detail was. Images I had never seen, stories I had never heard, drawings by survivors I had no idea even existed. These drawings, done post war, are detailed and don’t hold anything back. A hollow-looking prisoner holds a baby’s corpse by the leg in one, ready to fling him or her in the furnace.

As I navigate through the exhibition, glancing around, I can see that it is similarly moving strangers. I feel strange about breaking the sombre silence at first but then see two young women around my age whispering amongst themselves as they stand back to take in the blown up images on the walls.

I pluck up the courage to introduce myself to the one nearest to me, called Iris. I explain I’m writing an article and curiously ask her what brought her to this exhibition. “I’m from the Ukraine actually,” she explains, in lightly accented English. “We just came back from the real Auschwitz, but as we are filmmakers [she motions to her friend], we wanted to see how these atrocities are being presented, so we can capture what is going on in Ukraine in the most powerful way possible.”

Her eyes go misty. “My family are still there. It’s awful. Who would believe that this kind of slaughter is still happening in 2022?”

This is very much the theme of the last exhibit, which invites the viewer to watch a series of short films touching upon other contemporary genocides, such as Bosnian Muslims in Srebrenica and the Yazidi in Northern Iraq. There is also a short film focusing on how antisemitism still flourishes nowadays, showing Neo Nazi rallies and the shocking burning of Israeli flags on streets in the USA. It also touches on how Jew hatred manifests on social media, showing some racist users poking fun at Anne Frank’s murder.

Unfortunately, I have seen all too well how much of the antisemitism my peers and I experience on social media comes from the far left just as much as from the far right. This, in a way is even more deadly, because at least Hitler showed outright that he hated Jews. These days, it’s ‘fashionable’ to replace hating ‘Jews’ with hating ‘Zionists’, dehumanising us and moralising our murders, rendering ‘never again’ obsolete.

Moreover, in an age of Kanye West openly praising Hitler and the Nazis and with the growing normalisation of antisemitism and social media accounts brazenly posting heinous Holocaust denial, we NEED Holocaust education in our schools to be uncompromising in its depictions, much like this exhibition.

This ‘anti racist’ saturated misguided generation need to get that the Nazis murdered Jews because we aren’t white. Because we are not European. And yet we are too white for every other person wanting to kill us.

‘Never again’ and ‘we remember’ are meaningless to the masses ready to rewrite our history at a moment’s notice. We are ALWAYS the allies, always the first to stick up in the name of social justice, to go to BLM rallies, to chant slogans of solidarity.

The exhibition is available for schools to attend. In my opinion, this needs to be a mandatory school trip for all UK students.

What astounds me the most is that we’re all so concerned about the impact that seeing the ‘brutality of history’ will have on youth – the irony, when gang culture and violence is glorified, when spare time is spent virtually massacring characters in video games. A youth already obsessed with Nazi glorifying content on TikTok and Holocaust jokes and memes. As we say in Hebrew – תעשה לי טובה – do me a favour.

I leave the building newly inspired. Over the last few years I have dedicated my spare time to exposing and battling antisemitism on my social media account @partisanprincess.

It is exhausting work and vocal Jewish voices like mine are constantly threatened into silence by doxing as well as horrific threats. Sometimes, the pressure gets too much and I need to step back. But never will I give in. As the sage taxi driver told me on the drive home: “When the consequences of fighting antisemitism gets you down, remember that those who have gone before you lost their lives for speaking out and educating the world and so you must never be silent, for their sakes.”

Grab your tickets as soon as you can because Seeing Auschwitz is only in London for a limited amount of time (closing January 29th). www.seeing-auschwitz.com

Tickets are £16.80 for adults, £14.40 for students and 65+ and £12 for children. Part of the revenue generated by the exhibition will be used to help Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum in Poland in their efforts to ensure the long-term preservation and conservation of the authentic site.

Thank you for helping to make Jewish News the leading source of news and opinion for the UK Jewish community. Today we're asking for your invaluable help to continue putting our community first in everything we do.

For as little as £5 a month you can help sustain the vital work we do in celebrating and standing up for Jewish life in Britain.

Jewish News holds our community together and keeps us connected. Like a synagogue, it’s where people turn to feel part of something bigger. It also proudly shows the rest of Britain the vibrancy and rich culture of modern Jewish life.

You can make a quick and easy one-off or monthly contribution of £5, £10, £20 or any other sum you’re comfortable with.

100% of your donation will help us continue celebrating our community, in all its dynamic diversity...

Engaging

Being a community platform means so much more than producing a newspaper and website. One of our proudest roles is media partnering with our invaluable charities to amplify the outstanding work they do to help us all.

Celebrating

There’s no shortage of oys in the world but Jewish News takes every opportunity to celebrate the joys too, through projects like Night of Heroes, 40 Under 40 and other compelling countdowns that make the community kvell with pride.

Pioneering

In the first collaboration between media outlets from different faiths, Jewish News worked with British Muslim TV and Church Times to produce a list of young activists leading the way on interfaith understanding.

Campaigning

Royal Mail issued a stamp honouring Holocaust hero Sir Nicholas Winton after a Jewish News campaign attracted more than 100,000 backers. Jewish Newsalso produces special editions of the paper highlighting pressing issues including mental health and Holocaust remembrance.

Easy access

In an age when news is readily accessible, Jewish News provides high-quality content free online and offline, removing any financial barriers to connecting people.

Voice of our community to wider society

The Jewish News team regularly appears on TV, radio and on the pages of the national press to comment on stories about the Jewish community. Easy access to the paper on the streets of London also means Jewish News provides an invaluable window into the community for the country at large.

We hope you agree all this is worth preserving.