The Boy Who Drew Auschwitz: How one child survivor saw the Holocaust

Thomas Geve was just 13-years-old when he entered Auschwitz and began making sketches of the inhumanity he witnessed

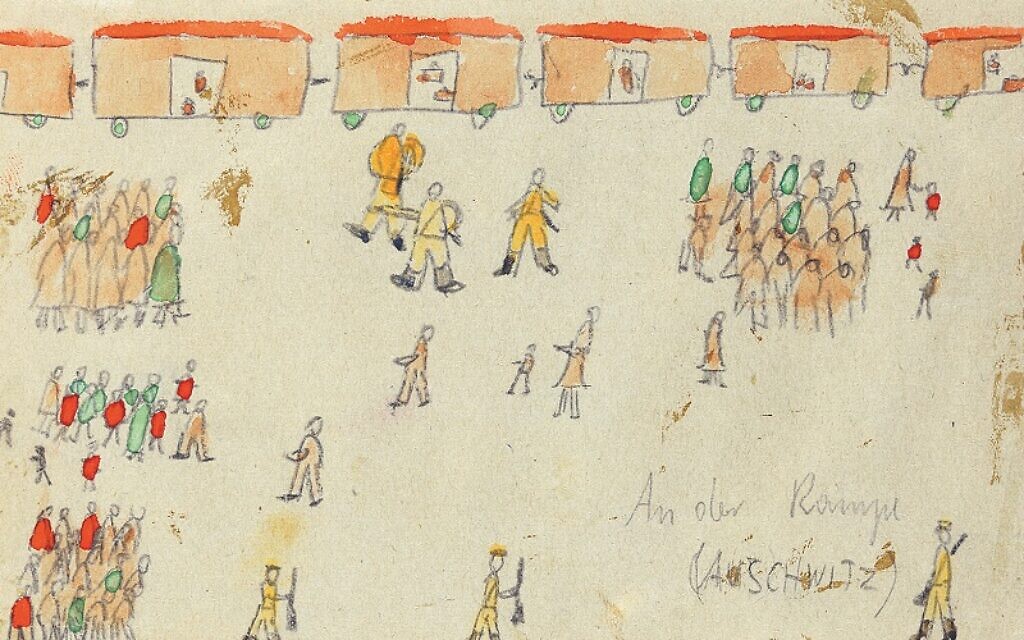

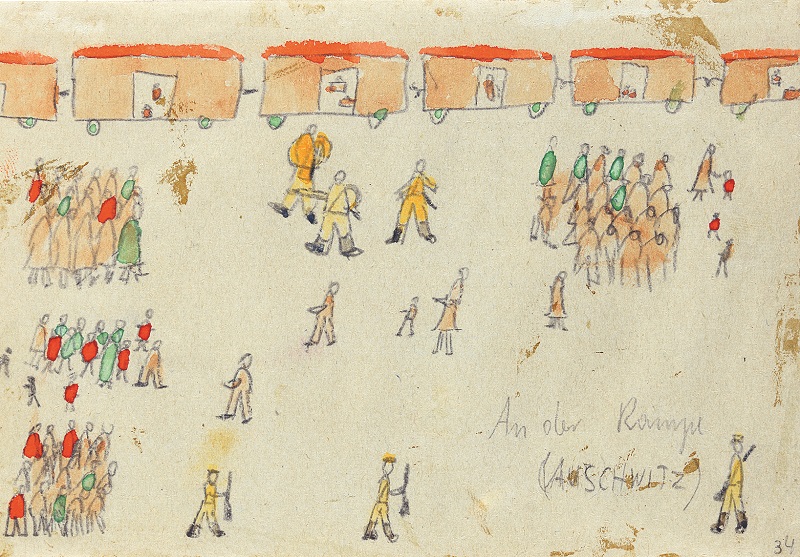

Thomas' sketch of the selection on the ramp was chosen to be etched onto a memorial wall at Auschwitz

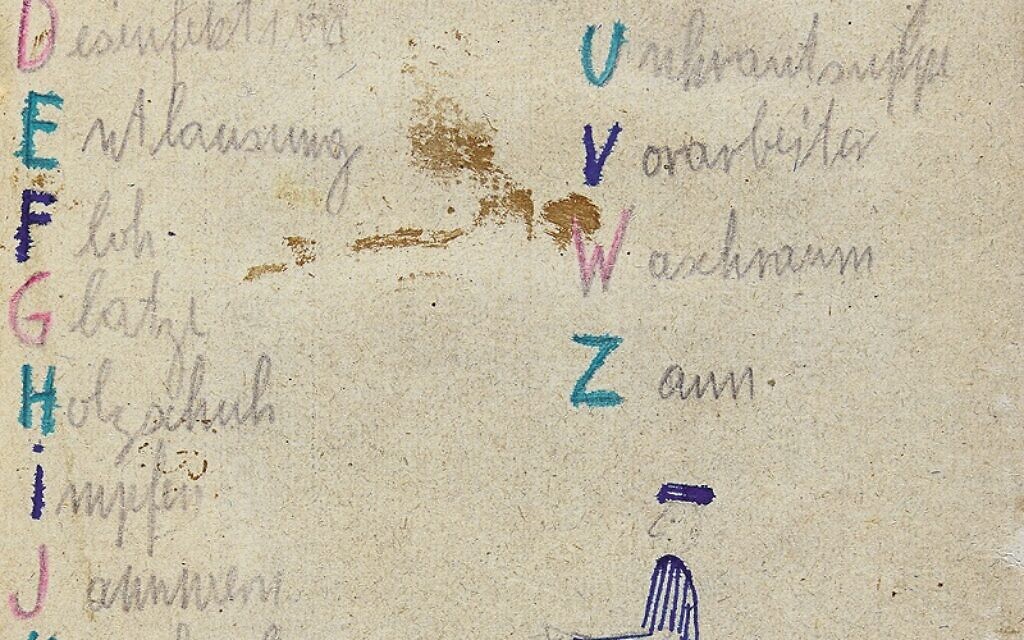

Thomas' sketch of the selection on the ramp was chosen to be etched onto a memorial wall at Auschwitz The ABC of an Auschwitzer

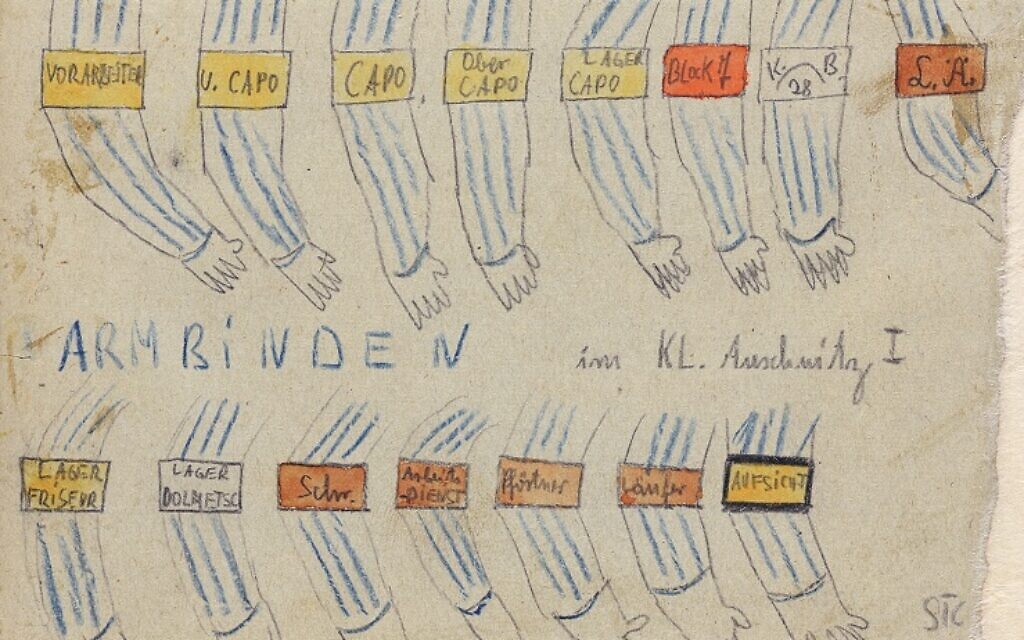

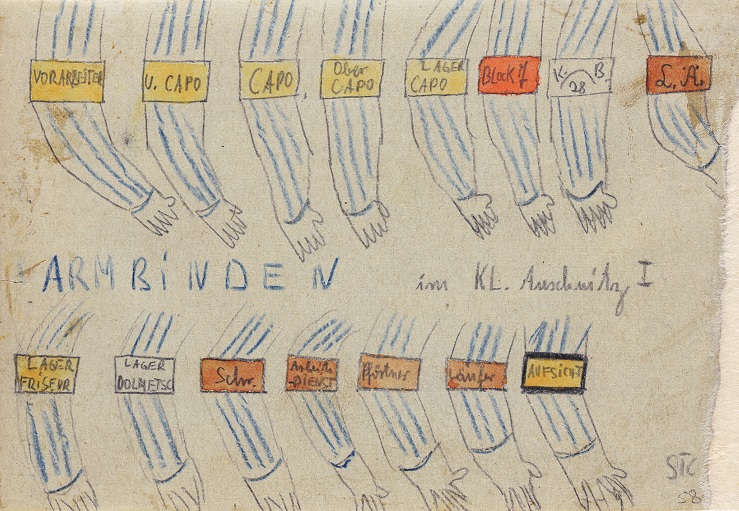

The ABC of an Auschwitzer Armbands showing the prisoner hierarchy at Auschwitz

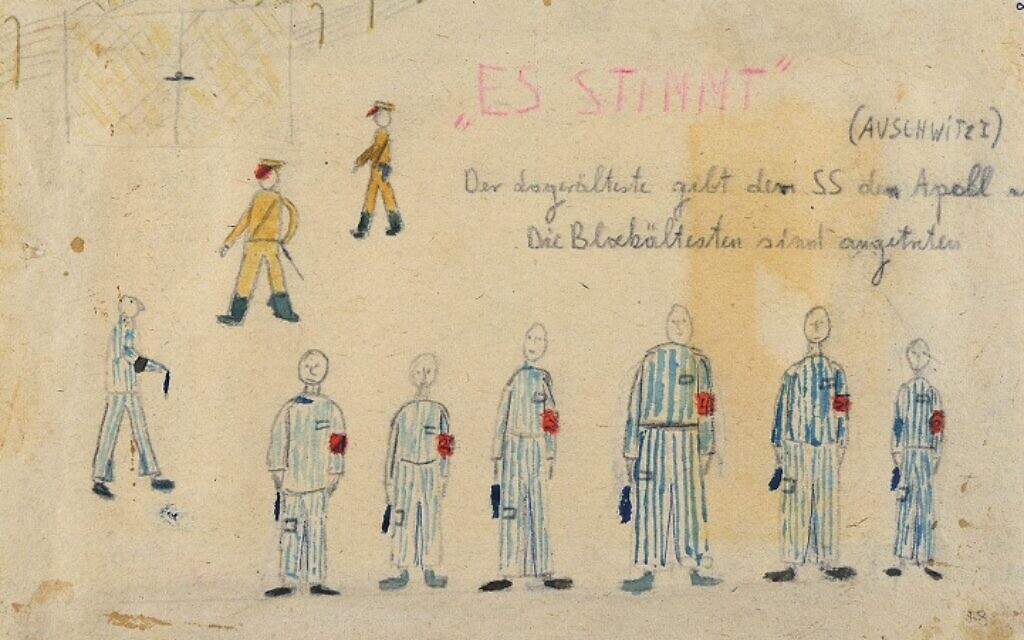

Armbands showing the prisoner hierarchy at Auschwitz The prisoners on roll call

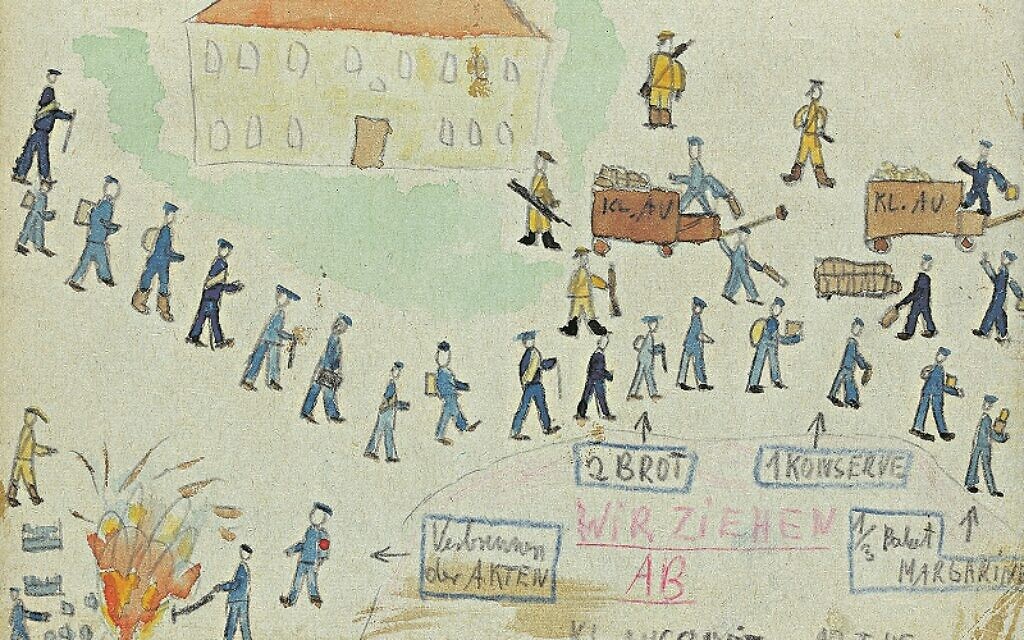

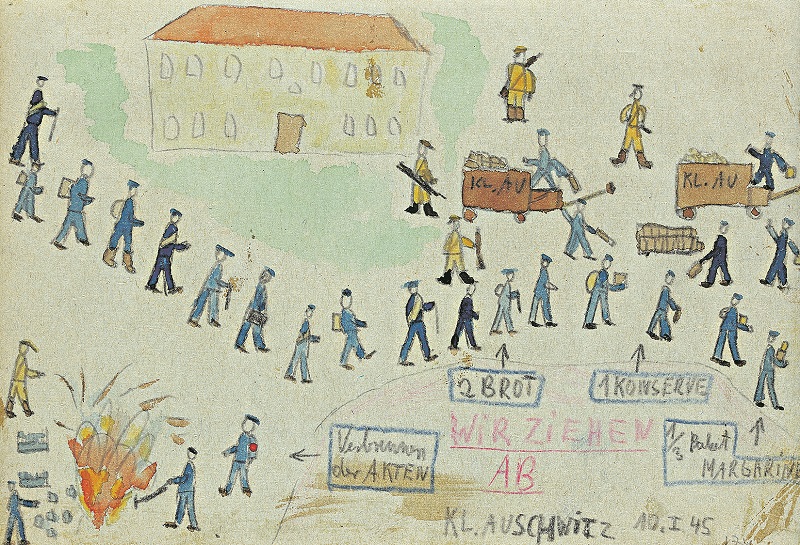

The prisoners on roll call Going on the Death March

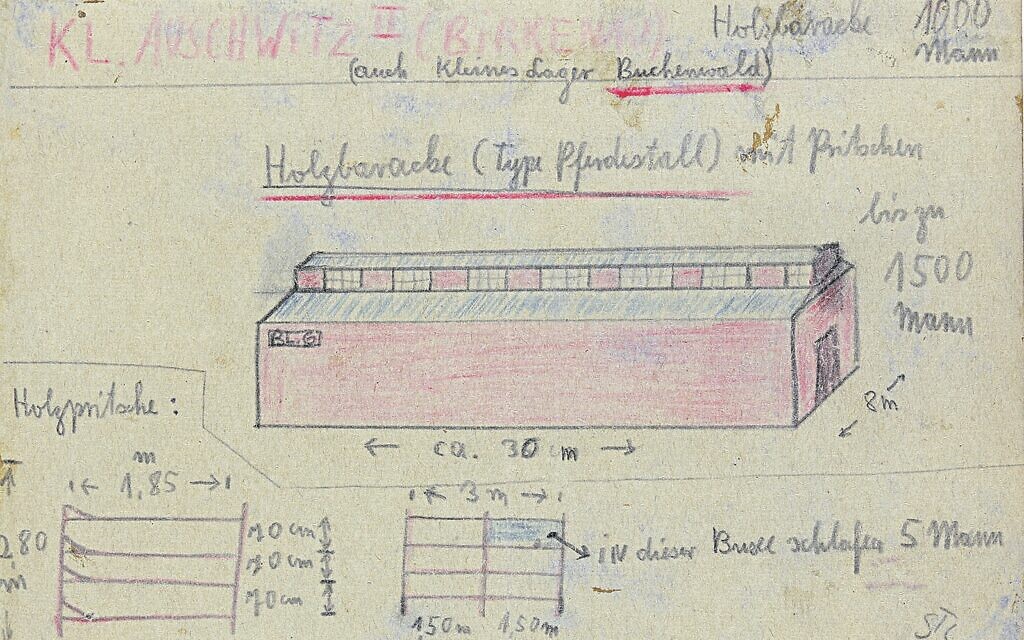

Going on the Death March The wooden barracks at Auschwitz

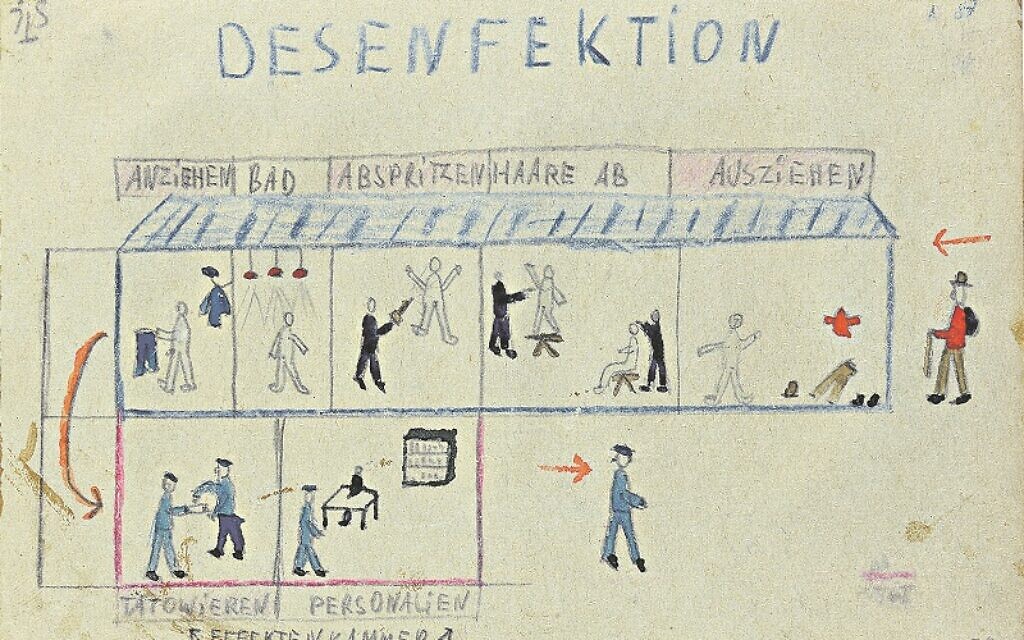

The wooden barracks at Auschwitz The disinfection process

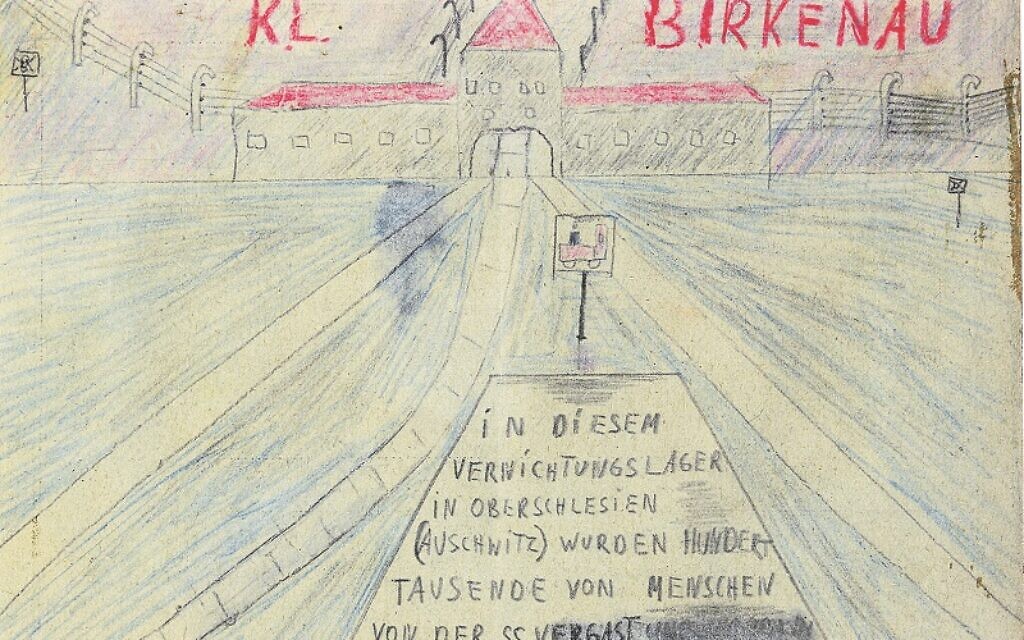

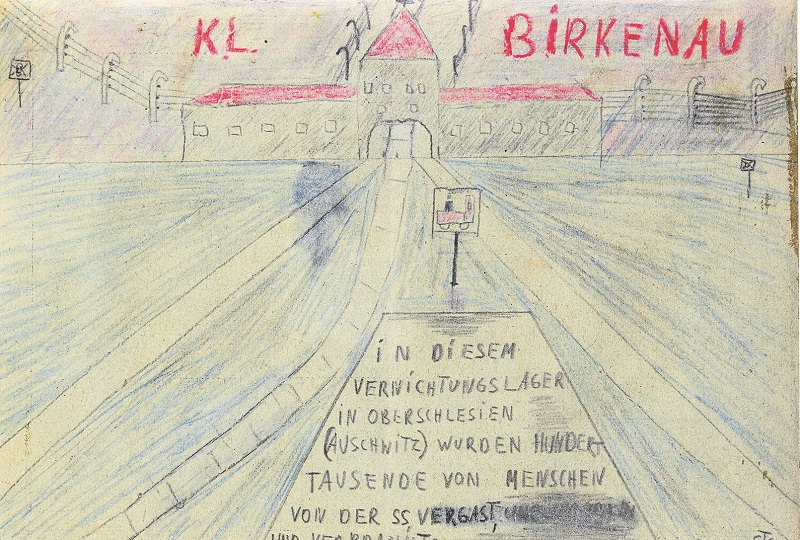

The disinfection process The entrance to Birkeanu concentration camp

The entrance to Birkeanu concentration camp

When words failed him, one 15-year-old boy who survived three Nazi concentration camps instead set about drawing a series of remarkable sketches to tell his story of the Holocaust.

At first, Thomas Geve’s impulse was simply to explain to his father – who managed to escape to England during the Second World War – all the unimaginable trauma he had endured.

But now 75 years later, Thomas’ etchings, created first with charcoal on pieces of cement sacks, and then in colour on scraps of paper no larger than a postcard, have taken on new meaning as one of the most remarkable testimonies of that time: the Holocaust seen through the eyes of a child.

Get The Jewish News Daily Edition by email and never miss our top stories Free Sign Up

For the first time, more than 80 of his sketches are presented alongside his narrative of events in The Boy Who Drew Auschwitz, published this week.

His poignant account, written with journalist Charlie Inglefield, recalls how Thomas was just nine when he waved farewell to his father, Erich, as he travelled from Berlin to England; how the family planned to join Erich, but that became an impossibility once the Second World War broke out; and how he stayed with his mother in the German capital working as a gravedigger – despite his tender age – until they were both deported to Auschwitz in 1943.

There he remained until the inmates were evacuated in January 1945 and sent on a death march, before enduring Gross-Rosen concentration camp and later Buchenwald, which was liberated in April 1945.

His incredible story of survival is interspersed with the drawings. Some are of everyday camp life, some show detailed lists, maps and statistics, while others show the sickening brutality of their oppressors.

One shows stickmen playing in a camp orchestra, while a row of faceless men, all uniformed and without individuality, march along to the music. Another shows, through a child’s eyes, the process of selection for death, or what happened to those who bravely tried to escape but were captured. Thomas even made drawings about what happened on the death march.

Speaking over a Zoom call from his home in Israel, where Thomas emigrated in 1950, the now 91-year-old survivor tells me the drawings serve as a continuous reminder of his story and why he feels it is imperative to continue to educate people about the Holocaust.

“I still think about it and know about it. It was my life,” he explains.

Born in Beuthen before moving to Berlin just before the outbreak of war, Thomas was just a youngster when he realised being Jewish could put his life in danger.

“I knew when I was five-years-old that I was Jewish because I was not allowed to play with the other children on the street anymore. They explained that I was something different. I even learned a song from the other children about Hitler and my family said, ‘My God, you’re not allowed to sing that song. You’re Jewish.’”

Thomas remained with his mother until their deportation to Auschwitz, where he was taken off to the men’s camp as one of 18,000 prisoners there and given a tattoo with the number 127003.

He says: “But I was just called 003 in Auschwitz; that was my name for more than two years.”

His sketch of new arrivals at the notorious death camp, which has been engraved on a special memorial wall at Auschwitz (pictured, main right), is for him “the most important and by far the saddest picture of modern history”.

He adds: “When we arrived, we didn’t really know what was happening. That was part of Hitler’s design, to hide all these things from the world. It didn’t really occur to me that we would be prisoners. I thought we were sent there to work in the factories, nothing more.”

But soon the reality of their situation became clear – and, aged 13, Thomas was still just a child – a fact he kept hidden from the SS officers, thanks to his tall stature, which made him seem older. Officially there were no men aged under 15 at the camp.

“Out of 18,000 men, I was the third youngest,” recalls Thomas, who was sent with other young men to become a bricklayer at the camp. “Because I was so tall, people didn’t recognise I was a child. But it was quite a struggle because I couldn’t fight or compete with the grown-ups. On the other hand, when people realised I was a child, they did their best to help me.”

One of the most remarkable stories that Thomas recalls in his book is how – for a very brief moment – he saw his mother again in the camp, with many people risking their lives to make that meeting happen.

One of the most remarkable stories that Thomas recalls in his book is how – for a very brief moment – he saw his mother again in the camp, with many people risking their lives to make that meeting happen.

In his book, Thomas recalls: “Still in her late 30s, Mother looked as haggard as her companions. Without either of us slowing our stride, we touched hands. I managed to sneak a kiss. To hold her hand again was an unimaginable, miraculous moment.”

Thomas would never see his mother again, but it was a moment he would never forget. Meanwhile, for the other camp inmates, the “one in a million chance” of a mother and son reuniting at Auschwitz provided a beacon of hope among the despair.

Thomas’ daughter, Yifat Meir, says the episode is particularly moving because of the risk others must have taken to help them.

“They helped each other to find those human moments. The camp was so much about erasing one’s identity as a person, but here they were helping each other just to feel human again.”

After liberation, Thomas was sent to an orphan camp in Switzerland, before finally being reunited with his father in England. He had begun drawing his experiences prior to the ending of the war, but it while recuperating in Switzerland that his work became more prolific.

Yifat believes the sketches provided a form of art therapy for the young teenager and inspired other child survivors to work through their trauma in the same way.

She adds: “My father kept telling me he used seven colours and it came to my mind that those are the colours of the rainbow, a symbol of peace and life.

“I think it was very healing for him to draw in colour to describe life in the camps. It was his way of taking back control over his life, having experienced so much suppression.”

The Boy Who Drew Auschwitz by Thomas Geve with Charlie Inglefield is published by Harper Non-Fiction priced £18.99 (hardback)

Thank you for helping to make Jewish News the leading source of news and opinion for the UK Jewish community. Today we're asking for your invaluable help to continue putting our community first in everything we do.

For as little as £5 a month you can help sustain the vital work we do in celebrating and standing up for Jewish life in Britain.

Jewish News holds our community together and keeps us connected. Like a synagogue, it’s where people turn to feel part of something bigger. It also proudly shows the rest of Britain the vibrancy and rich culture of modern Jewish life.

You can make a quick and easy one-off or monthly contribution of £5, £10, £20 or any other sum you’re comfortable with.

100% of your donation will help us continue celebrating our community, in all its dynamic diversity...

Engaging

Being a community platform means so much more than producing a newspaper and website. One of our proudest roles is media partnering with our invaluable charities to amplify the outstanding work they do to help us all.

Celebrating

There’s no shortage of oys in the world but Jewish News takes every opportunity to celebrate the joys too, through projects like Night of Heroes, 40 Under 40 and other compelling countdowns that make the community kvell with pride.

Pioneering

In the first collaboration between media outlets from different faiths, Jewish News worked with British Muslim TV and Church Times to produce a list of young activists leading the way on interfaith understanding.

Campaigning

Royal Mail issued a stamp honouring Holocaust hero Sir Nicholas Winton after a Jewish News campaign attracted more than 100,000 backers. Jewish Newsalso produces special editions of the paper highlighting pressing issues including mental health and Holocaust remembrance.

Easy access

In an age when news is readily accessible, Jewish News provides high-quality content free online and offline, removing any financial barriers to connecting people.

Voice of our community to wider society

The Jewish News team regularly appears on TV, radio and on the pages of the national press to comment on stories about the Jewish community. Easy access to the paper on the streets of London also means Jewish News provides an invaluable window into the community for the country at large.

We hope you agree all this is worth preserving.

-

By Laurent Vaughan - Senior Associate (Bishop & Sewell Solicitors)

-

By Laurent Vaughan - Senior Associate (Bishop & Sewell Solicitors)

-

By Laurent Vaughan - Senior Associate (Bishop & Sewell Solicitors)

-

By Laurent Vaughan - Senior Associate (Bishop & Sewell Solicitors)