Time travel to Jewish Provence

Benjamin Ramm delves into the twists and turns of two centuries of the Jews of Provence

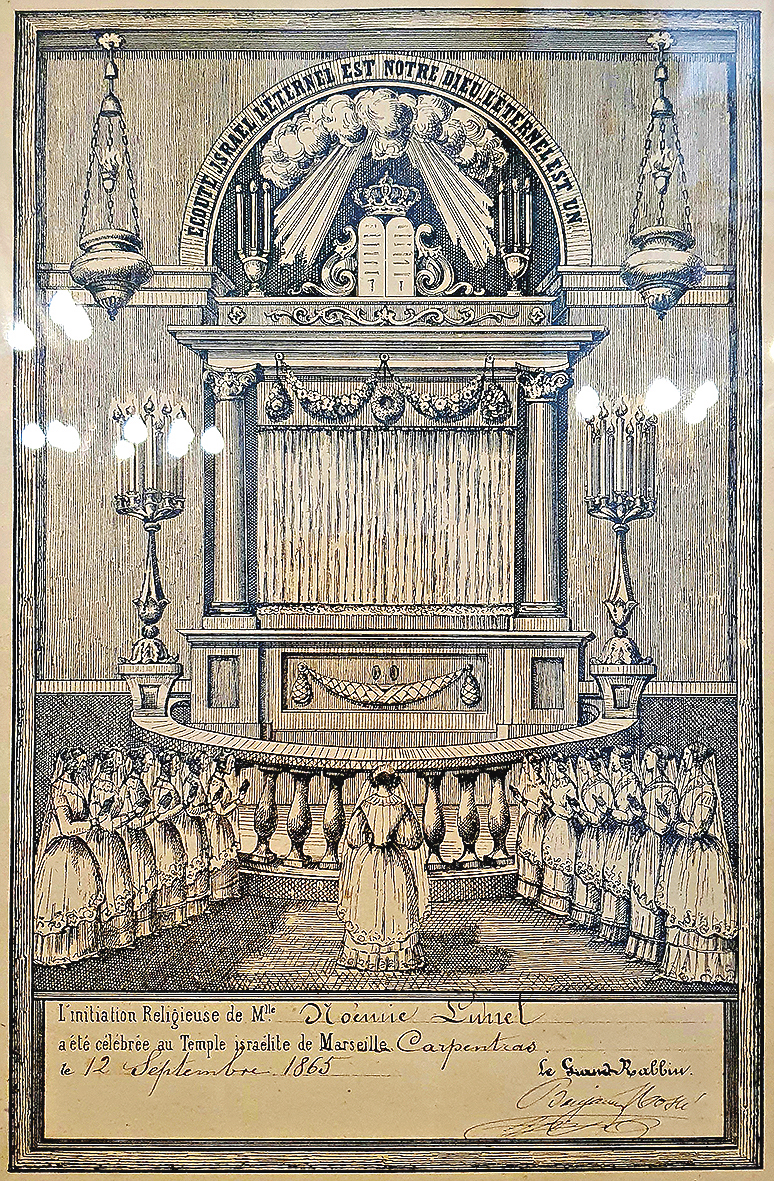

The town of Carpentras, in the Vaucluse region of Provence, is home to the oldest active Jewish community in western Europe and the second oldest on the continent (after Prague). It’s a little-known destination for travellers seeking to discover more about the 2,000-year cultural legacy of Jews in the region. Throughout its many incarnations, Jews have remained, nurturing a distinct cultural legacy.

In November 1940, Henri Dreyfus’s sixteen-year tenure as mayor of the Provençal town of Carpentras came to an abrupt end. A month earlier, the Pétain regime at Vichy had passed a law barring members of the ‘Jewish race’ from holding office. Dreyfus – the nephew of Alfred, whose ordeal helped define the Third Republic – was arrested in 1943, after the German invasion of the region, and deported to Drancy. He narrowly avoided being sent to Auschwitz, where his brother René perished. When the war ended, Henri returned to Carpentras, and was re-elected overwhelmingly to serve a final term as mayor.

This story is a small but significant chapter in the history of Carpentras. Jews first arrived in Provence more than 2,000 years ago, landing at Marseille in the company of Greek merchants. The region has been both a cultural innovator and a neglected backwater; once part of the Holy Roman Empire, it became a seat of papal power before being subsumed into the French state. Throughout its many incarnations, the Jews have remained – resolute, at times flourishing, often suffering, and always nurturing a distinct cultural legacy.

Get The Jewish News Daily Edition by email and never miss our top stories Free Sign Up

During my visit, community elder Alain Freund gave me a tour of the synagogue – the oldest in France still in activity – and described how, 500 years ago, “they had to build up eight, nine, 10 storeys”. Forbidden from owning property, Jews were obliged to wear a yellow symbol, and by the 16th century their professions were restricted to second-hand trading and usury.

There was even a prohibition on windows that looked onto the town. Forced inward, this community soon developed its own dialect, Judéo-Comtadin, of the language Shuadit (or Judéo-Occitan) spoken in Provence.

Life in the ghetto revolved around the elegantly ornamented synagogue, which attended to every aspect of community life, from the mikveh to the shechita. The site had two bakeries: one for challah (with an oven forge that could fit up to 2,000 loaves) and another for unleavened bread at Passover. The synagogue was twice enlarged during the 18th century, in the Provençal baroque style, to reflect the growing community – a tenth of the town’s population.

After the revolution, the Provençal rite was replaced by the Portuguese Sephardic liturgy, which is still used by the community today. Emancipation led to a degree of assimilation, and use of Judéo-Provençal declined. Alain tells me that one elderly lady still speaks a smattering of the dialect, but the last fluent speaker was Armand Lunel, a prominent writer who died in 1977. In 1926, Lunel won the inaugural Prix Renaudot for his novel, Nicolo-Peccavi, or The Dreyfus Affair in Carpentras.

The decline of Judéo-Comtadin raises some tricky questions about the nature of Jewish identity in a secular age. How do we mourn the loss of a

language that emerged as a consequence of ghettoisation? Every dialect is a unique way of seeing and being in the world, and its disappearance is a kind of obliteration of memory. But in recent years, particularly among Ashkenazi activists uncomfortable with Zionism, there has been a tendency to fetishise the ghetto – which ignores why so many Jews left as soon as they could. The corollary of these questions is: what does it mean to be Jewish in an environment in which the threat of extinction is not self-defining?

This was not something the Jews of Provence had the luxury of finding out for themselves. Between 1941 and 1942, le Camp des Milles, outside Aix-en-Provence in Bouches-du-Rhône, was used as a transit camp for 2,000 Jews who were deported to Auschwitz, via Drancy. A museum at the site commemorates their journey. The Italian armistice with the Allies prompted the Germans to invade Provence on 8 September 1943, after which they formed specialised units to hunt down Jews. Within five months, 5,000 were caught and deported to Auschwitz.

After the war, the community of Carpentras welcomed Jews from Morocco, Tunisia, Libya and Algeria. The majority of the present community is from this region, including Alain’s Tunisian wife, Katia, who is the public face of the Association for the Enhancement of the Jewish Heritage of Carpentras. Alain is the sole Ashkenazi member of the congregation.

The community today gathers on High Holy Days, and for a once-monthly Shabbat service, in the majestic prayer hall on the synagogue’s first floor. Alain opens the ark to reveal, behind a partition, two dozen Sifrei Torah, beautifully adorned and carefully maintained. Opposite is a spiral pulpit in the style of a baroque church, with a view of the most curious feature: Elijah’s armchair – a small, gilded, red velvet throne, for the ‘prophet of children’ to witness the circumcision of baby boys.

On a sultry Friday in June, congregants milled around the synagogue square. The Shabbat service was informal and convivial, led by Dr Meyer Benzekrit, a charismatic Ladino-speaking dentist of Turkish origin. The minyan seemed like a large family, with each member keeping alive a flame that ought to have been extinguished long ago, but which – despite everything – still burns after seven centuries.

Excerpted with permission from issue 247 of The Jewish Quarterly

Where to stay in Provence

LUXURY

Owned by a Jewish family, Crillon Le Brave is a chic, rustic 34-bedroom hotel nestled within a sleepy village eponymous of the Vaucluse region. The views over the Provence countryside are spectacular. Refurbished in 2020, it is a stone’s throw away from beautiful vineyards, including Châteauneuf-du-Pape.

FOODIE

Chef Alain Ducasse’s Hostellerie de l’Abbayede la Celle is a charming boutique hotel set in the middle of the vineyards of the Coteaux Varois, close to many pretty villages. The restaurant has a Michelin star. From £138 a night.

WALKING

Explore a wide range of walking routes from the charming Hotel du Poète in Fontaine-de-Vaucluse and visit hilltop villages and Roman monuments. The beautifully-decorated hotel has been converted from a 19th century water mill on the banks of the River Sorgue. From £1,245 for seven nights’ B&B, including seven days’ car hire, return rail from London St Pancras, one dinner at a local restaurant, GPS navigation, walking maps and cultural notes.

CYCLING

Cycling for Softies offers tailor-made gourmet cycling adventures across France and Provence is a favourite. You can veer off the well-trodden path, take scenic country roads and be privy to the beautiful landscapes while staying in boutique hotels along the way.

CANAL

Experience the beauty of Provence from the Canal du Midi. There is a range of different size boats to sleep between two and seven people.

SELF-CATERING

Just outside the little village of Lioux, a short drive away from Roussillon and the pretty Provençal perched villages, Villa Madeleine sleeps six in three king-sized bedrooms with a swimming pool and covered terrace. From £,1099 for seven nights.

Thank you for helping to make Jewish News the leading source of news and opinion for the UK Jewish community. Today we're asking for your invaluable help to continue putting our community first in everything we do.

For as little as £5 a month you can help sustain the vital work we do in celebrating and standing up for Jewish life in Britain.

Jewish News holds our community together and keeps us connected. Like a synagogue, it’s where people turn to feel part of something bigger. It also proudly shows the rest of Britain the vibrancy and rich culture of modern Jewish life.

You can make a quick and easy one-off or monthly contribution of £5, £10, £20 or any other sum you’re comfortable with.

100% of your donation will help us continue celebrating our community, in all its dynamic diversity...

Engaging

Being a community platform means so much more than producing a newspaper and website. One of our proudest roles is media partnering with our invaluable charities to amplify the outstanding work they do to help us all.

Celebrating

There’s no shortage of oys in the world but Jewish News takes every opportunity to celebrate the joys too, through projects like Night of Heroes, 40 Under 40 and other compelling countdowns that make the community kvell with pride.

Pioneering

In the first collaboration between media outlets from different faiths, Jewish News worked with British Muslim TV and Church Times to produce a list of young activists leading the way on interfaith understanding.

Campaigning

Royal Mail issued a stamp honouring Holocaust hero Sir Nicholas Winton after a Jewish News campaign attracted more than 100,000 backers. Jewish Newsalso produces special editions of the paper highlighting pressing issues including mental health and Holocaust remembrance.

Easy access

In an age when news is readily accessible, Jewish News provides high-quality content free online and offline, removing any financial barriers to connecting people.

Voice of our community to wider society

The Jewish News team regularly appears on TV, radio and on the pages of the national press to comment on stories about the Jewish community. Easy access to the paper on the streets of London also means Jewish News provides an invaluable window into the community for the country at large.

We hope you agree all this is worth preserving.

-

By Brigit Grant

-

By Laurent Vaughan - Senior Associate (Bishop & Sewell Solicitors)

-

By Laurent Vaughan - Senior Associate (Bishop & Sewell Solicitors)

-

By Laurent Vaughan - Senior Associate (Bishop & Sewell Solicitors)

-

By Laurent Vaughan - Senior Associate (Bishop & Sewell Solicitors)