What happened to Germans who didn’t support Hitler?

Peter Clenott's historical mystery thriller novel considers the fate of those who were not willing participants of Nazism

On the face of it, writer Peter Clenott’s grandfather was guilty of committing the ultimate betrayal.

He was a Harvard graduate, a World War One veteran, a decorated airbase commander in Iceland during the Second World War; and then in the years following, the chief prosecutor overseeing the conviction of 15 Nazis at the Dora Trial, held at Dachau concentration camp in Germany in 1947.

William Berman’s achievements were notable, but he was also harbouring a secret. During his time overseas the leading American-Jewish lawyer had an affair with a German woman, resulting in an illegitimate daughter.

The child and her mother were shunned by Berman’s family and Clenott admits having “no connection” to or knowing the whereabouts of his half-aunt, who by now would be in her mid-70s if she were still alive.

But his interest was piqued by those post-war events and he wanted to understand how his grandfather came to be in a relationship with a German woman. The 72-year-old author began reading more books about the period, including on the Holocaust, the Third Reich and the aftermath of the Second World War, inspiring him to pen his latest work.

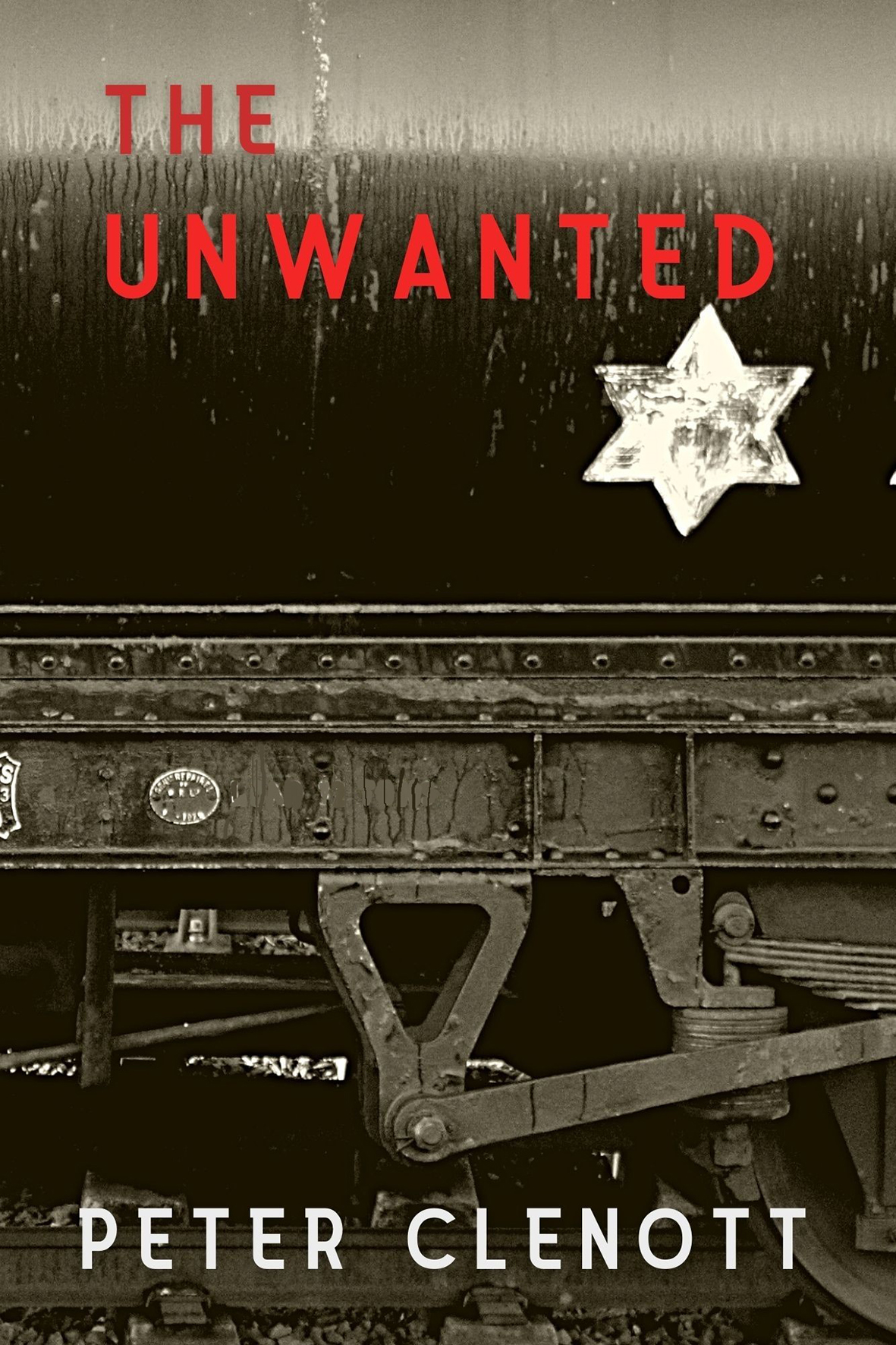

Clenott, who has written screenplays, short stories and full-length novels for the best part of 50 years, credits his grandfather’s secret as the starting point for his historical mystery thriller The Unwanted.

A key theme of the novel, which revolves around two teenage girls who become embroiled in the murders of an American official and a fleeing SS officer, is that not all Germans were willing participants of Nazism and in fact many suffered at the hands of the brutal policies instituted by Hitler.

The keen writer, who lives just outside of Boston and works for a non-profit organisation helping people facing homelessness, explains: “I learned that after the war ended, the situation worsened for many German women – two million of them were raped after the war by the Russians, but also by American, British and French soldiers. There were hundreds of thousands of children born out of rape.

“And it wasn’t unusual for German women wanting to avoid the poverty that existed after the Second World War or coming under the leadership of a communist regime, intentionally trying to strike up relationships to escape that.

“My grandfather was around 53 at the time, an attractive man, an attorney and officer. I don’t really know the details about what happened, but you can perhaps understand some of the reasons why it did.”

During the course of his research, Clenott also came across chilling detail about the Nazi’s Euthanasia Programme – the systemic murder of institutionalised patients with physical and mental disabilities – which began in 1939. The aim of it was to restore the racial ‘integrity’ of the German nation and it was in many ways a forerunner to the Nazis’ systemic murder of Jews in Europe as part of the Final Solution.

Clenott explains: “The Nazis took a popular eugenics idea at the time – sterilisation – and went a step further. They wanted to create a pure race. They didn’t want Jews, but they also didn’t want gypsies or homosexuals. They didn’t want people who were bipolar or had manic depression or any other mental or physical disability that would be a burden on the German state. The Nazis came up with a phrase: ‘Life unworthy of life’. People were encouraged to voluntarily give up their child to one of these euthanasia centres in Germany and Austria for ‘treatment’.”

The author poignantly acknowledges that his son, who is autistic and gay, would almost certainly have been a candidate for such centres during the Nazi era, excluding the fact that he is also Jewish. An estimated 10,000 physically and mentally disabled children were murdered out of 250,000 individuals overall as part of Nazi Germany’s euthanasia programme. Clenott based one of his main characters, 14-year-old Hana Zigler, against this scenario. As a result of her obsessive-compulsive tendencies, and because of suspicions that her mother had an affair with a Jewish man, Hana is taken by her merciless grandfather to an institute to be euthanised.

Despite the novel’s dark opening, there’s a twist ahead in the guise of Silke Hartenstein, a 16-year-old member of the Bund Deutsch Madel, the girls’ wing of the Hitler Youth movement. With her blonde hair and blue eyes, Silke looks every inch the archetypal Aryan, but beneath the surface she is becoming increasingly disillusioned with the Nazis, especially when she is pressured to have a child as a way of passing on her ‘perfect’ genes.

Despite the novel’s dark opening, there’s a twist ahead in the guise of Silke Hartenstein, a 16-year-old member of the Bund Deutsch Madel, the girls’ wing of the Hitler Youth movement. With her blonde hair and blue eyes, Silke looks every inch the archetypal Aryan, but beneath the surface she is becoming increasingly disillusioned with the Nazis, especially when she is pressured to have a child as a way of passing on her ‘perfect’ genes.

“I wanted her to be someone who is sympathetic, someone who was appalled by the Nazis. When she meets Hana she’s horrified by what she sees at the euthanasia centre and is drawn to help her. Silke is heroic in many ways, because she is unafraid to stand up to the Nazis and comes from a family that raised her to be a decent human being.”

At the core of the page-turning murder mystery is the close bond that develops between Silke and Hana and their impetus to survive against the odds.

Having widened his knowledge around the Holocaust, has Clenott changed his thoughts at all on Germany society at that time?

“My perspective definitely changed,” he admits. “They weren’t all Nazis, they weren’t all bad. Many good people suffered. We learn at school that wars have a start date and an end date, but in actual fact they don’t. The Second World War didn’t end with the Allies’ victory, because the suffering continued for many years after, particularly for women. The rapes, the violence, the threat of hunger and starvation, displacement and homelessness, the arrival of the Communists and so forth. It was a nightmare for millions that went on for years.”

For Clenott, perhaps the biggest lesson he learned in writing his novel is that the terrifying events of the past on which his story is based could, he believes, “absolutely happen all over again. Only recently we had neo-Nazis marching down the street saying, ‘Jews will not replace us’ – and Trump telling everyone those are ‘nice’ people. We have to learn what could happen even in a democracy. It really could happen again, so it’s important that we have good people who come together and are brave enough to fight the darkest side of humanity.”

The Unwanted by Peter Clenott is published by Level Best Books, £13.99

Thank you for helping to make Jewish News the leading source of news and opinion for the UK Jewish community. Today we're asking for your invaluable help to continue putting our community first in everything we do.

For as little as £5 a month you can help sustain the vital work we do in celebrating and standing up for Jewish life in Britain.

Jewish News holds our community together and keeps us connected. Like a synagogue, it’s where people turn to feel part of something bigger. It also proudly shows the rest of Britain the vibrancy and rich culture of modern Jewish life.

You can make a quick and easy one-off or monthly contribution of £5, £10, £20 or any other sum you’re comfortable with.

100% of your donation will help us continue celebrating our community, in all its dynamic diversity...

Engaging

Being a community platform means so much more than producing a newspaper and website. One of our proudest roles is media partnering with our invaluable charities to amplify the outstanding work they do to help us all.

Celebrating

There’s no shortage of oys in the world but Jewish News takes every opportunity to celebrate the joys too, through projects like Night of Heroes, 40 Under 40 and other compelling countdowns that make the community kvell with pride.

Pioneering

In the first collaboration between media outlets from different faiths, Jewish News worked with British Muslim TV and Church Times to produce a list of young activists leading the way on interfaith understanding.

Campaigning

Royal Mail issued a stamp honouring Holocaust hero Sir Nicholas Winton after a Jewish News campaign attracted more than 100,000 backers. Jewish Newsalso produces special editions of the paper highlighting pressing issues including mental health and Holocaust remembrance.

Easy access

In an age when news is readily accessible, Jewish News provides high-quality content free online and offline, removing any financial barriers to connecting people.

Voice of our community to wider society

The Jewish News team regularly appears on TV, radio and on the pages of the national press to comment on stories about the Jewish community. Easy access to the paper on the streets of London also means Jewish News provides an invaluable window into the community for the country at large.

We hope you agree all this is worth preserving.