The last goodbye… a journey of despair, hope and discovery

In publishing a book about his family’s path through the Holocaust, former MP Peter Bradley hopes to make his grandparents’ lives more significant

Long ago, in January 2005, I wrote an article for a local newspaper – a monthly column to which MPs attach surpassing significance, but no-one else reads. Except this piece was not the routine account of a momentous week in Westminster and heroic endeavours in the constituency. This one was written to mark Holocaust Memorial Day and it was deeply personal. And fully 17 years later, those 750 words have become a book of 100,000.

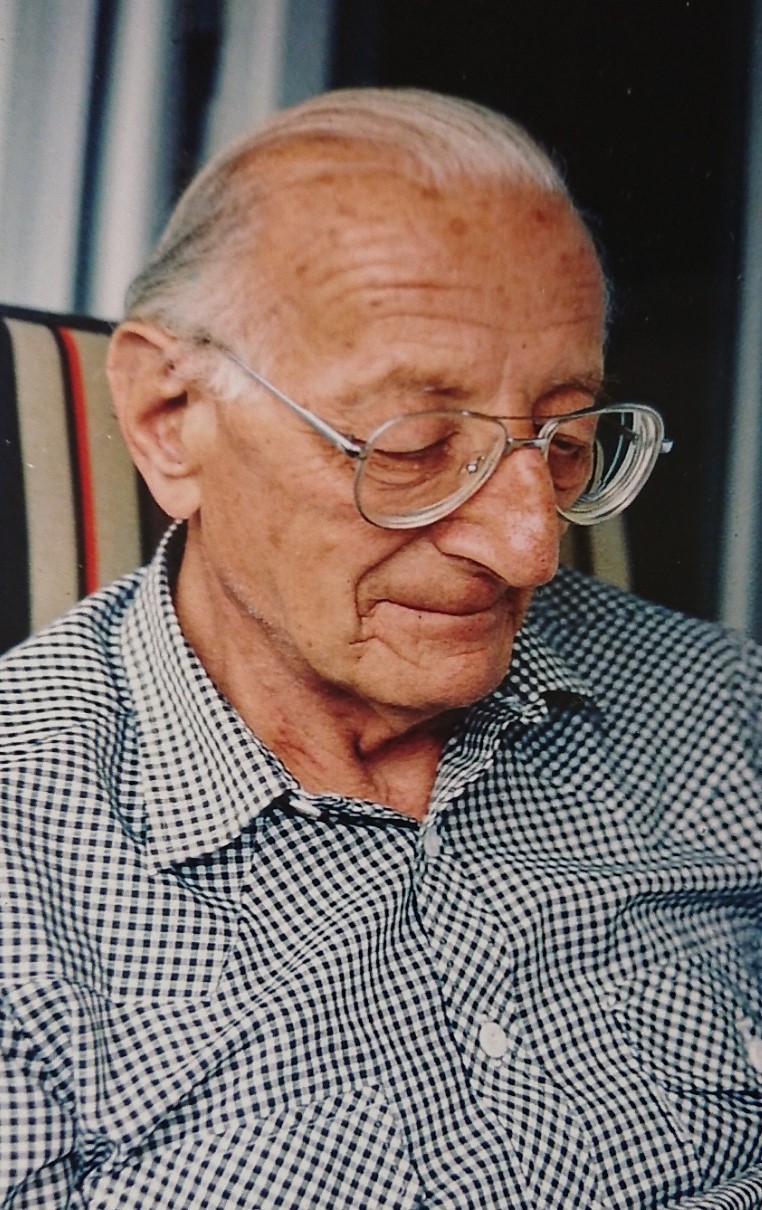

My father Fred Bradley (originally Fritz Brandes) had died some six months earlier, on 10 May 2004, the 65th anniversary of his flight from Nazi Germany after five terrible months in Buchenwald. He had rarely spoken of those times and barely touched on them in the brief family history he wrote towards the end of his life. But to it, he had appended a copy of the letter he had sent his parents shortly after his arrival in London. It was that letter, written on a park bench on Hampstead Heath, that inspired my article.

In stilted schoolboy English, he recounts “of what kind my deepest impressions were in the first few days I spent in this country”. He extols the courtesy and honesty of the English and the helpful geniality of their police; he marvels that women smoke in public and wear bathing suits in the parks, and that men push prams, carry bags and fly kites; and, of course, everyone talks about the weather. He reassures his parents, a little naively, that it’s so easy to strike up conversation with fellow passengers on the bus that, “when you come here, you will soon learn this language”.

But, in his heart, he knew they would not come. He had said his last goodbye as he boarded the train for the Channel coast at Frankfurt South station in May 1939. The train his parents took in November 1941 carried them to the camps in Latvia.

And it was that image, of the two trains – one heading west to freedom, the other east to destruction – that haunted me for the best part of a decade, and, in the end, drove me to spend seven years researching and writing my book.

Initially I had had a very limited plan – to follow the route of the transport which bore 1,000 Bavarian Jews from Nuremberg to Riga, a fate which only 52 survived. I can’t explain why I felt the need to make that journey. It simply insinuated itself, at first subtly, but then with growing insistence. Finally, I felt I had no choice.

Had I been able to identify the precise path of Sonderzug Da 35, I may have made my symbolic pilgrimage and left it at that. But no reliable record could be found and, in any event, the rail tracks have long been uprooted from large spans of eastern Poland, Lithuania and Latvia through which the ‘special train’ will have passed.

That was not the end of it though, for my failed attempt to find the answer to a single, discrete question prompted a multitude more about the fate of my grandparents. I wanted to know what had happened to them during the Nazi years. Above all, I needed to understand why it happened, how their fellow citizens – their neighbours, their business acquaintances, the customers at their draper’s shop, the people they knew – had come to put them on that train.

My quest led me from family papers to archives and libraries, from scholarly works to the testimony of survivors. It led me to the beautiful city of Bamberg in which my father had grown up and which, despite everything, he loved so well for the rest of his life; it led me to Buchenwald and to Riga.

At the heart of the narrative I came to write is the story of my family as it threads emblematically through a broader and longer history – from its confinement in the Frankfurt ghetto in the late 1400s to the sporadic successes and the regular reversals of the next 300 years, to my great-grandfathers’ new-found freedoms and prosperity in the nineteenth century, to the obliteration of their hopes and of their children and grandchildren in the twentieth.

And, perhaps inevitably, as I wrote, the scope of my book widened. I began the first draft against what was, for me as for others, an extremely unsettling backdrop. The UK had just voted to leave the EU and Donald Trump had won the US Presidential election. Across Europe and elsewhere, populists were enflaming ancient or imagining new grievances as they bid for votes, while authoritarian leaders in power unpicked the constitutions of once stable democracies. We had entered a time of turbulence, uncertainty and unreason in which simple solutions to complex problems appear so alluring to so many. For the first time in my life, I felt that the world may not be the safe place I had always taken it to be.

So, one question led to another – about how societies come to reject liberal values, and about the origins and persistence of the misbeliefs which permeate our shared European culture.

My father’s experience reveals the best of Britain, but also the worst. He was eternally grateful for the sanctuary it afforded him. He respected its institutions and cherished its democratic values. He was very happy to become a British citizen and to raise his family in a free society.

But he had been one of the very few Jewish refugees allowed here in the 1930s. Of the 500,000 who, in the gravest danger, applied for entry visas, only 70,000 were admitted. Though we take justifiable pride in the Kindertransport, which saved some 10,000 Jewish children, we should also acknowledge that we kept their parents out. Very few lived to see their sons and daughters again. Like my grandparents, they were held in a trap from which no-one would free them. This was not the first time that this country had turned its face against the desperate victims of persecution and conflict; it has not been the last.

And my father had not exactly been welcomed here. His visa was temporary and, barred from working, he subsisted on handouts from Jewish charities. When war broke out, his attempts to enlist were rejected because of his ‘suspect background’ and, when the Nazis invaded the Low Countries in May 1940, he was arrested as an ‘enemy alien’ and shipped across the Atlantic to a Canadian internment camp. It took two long years before the authorities learned to distinguish between the Jewish and political refugees and the committed Nazis and German POWs with whom they were imprisoned. Then, at last, my father was released and recruited.

As others have argued in different contexts, it is important that we re-examine our assumptions about our history and character. We need to understand our failings as well as our virtues, because the choices we make about our future depend to a significant extent on what we think we know about our past.

In the course of my research, I came across another, little-known history, of how the Danes, though under Nazi occupation from 1940, saved almost all their Jewish fellow citizens from deportation and death by spiriting them across the Öresund to neutral Sweden. They made a choice, different to that of the Germans who supported or succumbed to Nazism, different to that of the collaborators who abetted their destruction of European Jewry. The Danes made their choice, acted on it and were prepared to face the consequences, because, collectively, they decided that it was the right thing to do.

My book is not simply about the past, nor solely about Jews and Gentiles. For there is one more question: in a letter to a cousin shortly after the war, my father asked: “If Hitler had persecuted only gypsies, how many of us would have stuck our necks out to show kindness to them?”

If we’re honest, that question is unanswerable. But it’s also inescapable. As my book concludes, the past shapes but does not determine the future: “In the events of our own times, we are all perpetrators, or bystanders, or victims or resisters, or perhaps more than one at once. The question is: which of those roles do we choose for ourselves?”

My book fulfilled another, more personal purpose. It’s not by chance that in recent years a new literary genre has developed. Many of my generation, the sons and daughters of Holocaust survivors, brought up in safe havens and largely ignorant of the trauma their parents endured, have felt the need to ask the questions they could not put to them when they were living. It is as if there is an absence which must be acknowledged, an emptiness which must be filled.

In telling my grandparents’ story, I wanted somehow to make their abbreviated lives more significant, to reclaim for them their individuality and the humanity that had been stolen from them. I wanted them, through me, to have the last word.

The Last Train – A Family History of the Final Solution is published by HarperNorth

This piece was originally published in Order! Order! on 26 March 2022

Thank you for helping to make Jewish News the leading source of news and opinion for the UK Jewish community. Today we're asking for your invaluable help to continue putting our community first in everything we do.

For as little as £5 a month you can help sustain the vital work we do in celebrating and standing up for Jewish life in Britain.

Jewish News holds our community together and keeps us connected. Like a synagogue, it’s where people turn to feel part of something bigger. It also proudly shows the rest of Britain the vibrancy and rich culture of modern Jewish life.

You can make a quick and easy one-off or monthly contribution of £5, £10, £20 or any other sum you’re comfortable with.

100% of your donation will help us continue celebrating our community, in all its dynamic diversity...

Engaging

Being a community platform means so much more than producing a newspaper and website. One of our proudest roles is media partnering with our invaluable charities to amplify the outstanding work they do to help us all.

Celebrating

There’s no shortage of oys in the world but Jewish News takes every opportunity to celebrate the joys too, through projects like Night of Heroes, 40 Under 40 and other compelling countdowns that make the community kvell with pride.

Pioneering

In the first collaboration between media outlets from different faiths, Jewish News worked with British Muslim TV and Church Times to produce a list of young activists leading the way on interfaith understanding.

Campaigning

Royal Mail issued a stamp honouring Holocaust hero Sir Nicholas Winton after a Jewish News campaign attracted more than 100,000 backers. Jewish Newsalso produces special editions of the paper highlighting pressing issues including mental health and Holocaust remembrance.

Easy access

In an age when news is readily accessible, Jewish News provides high-quality content free online and offline, removing any financial barriers to connecting people.

Voice of our community to wider society

The Jewish News team regularly appears on TV, radio and on the pages of the national press to comment on stories about the Jewish community. Easy access to the paper on the streets of London also means Jewish News provides an invaluable window into the community for the country at large.

We hope you agree all this is worth preserving.