Claudia Roden: ‘What else do we have to give in life other than good food?’

The queen of Sephardi cuisine talks recipes, Marks & Spencer and Jewish history

There was a time, not long ago, when Ashkenazim and Sephardim were so far apart in their food choices that ne’er the chrayne would meet.

Claudia Roden, cookbook writer and doyenne of Sephardi-Jewish cuisine, who has spent a lifetime gathering recipes from exiled and migrating families that would otherwise have disappeared forever, knows first-hand just how unreceptive Ashkenazi British Jews once were to foods deemed “exotic”.

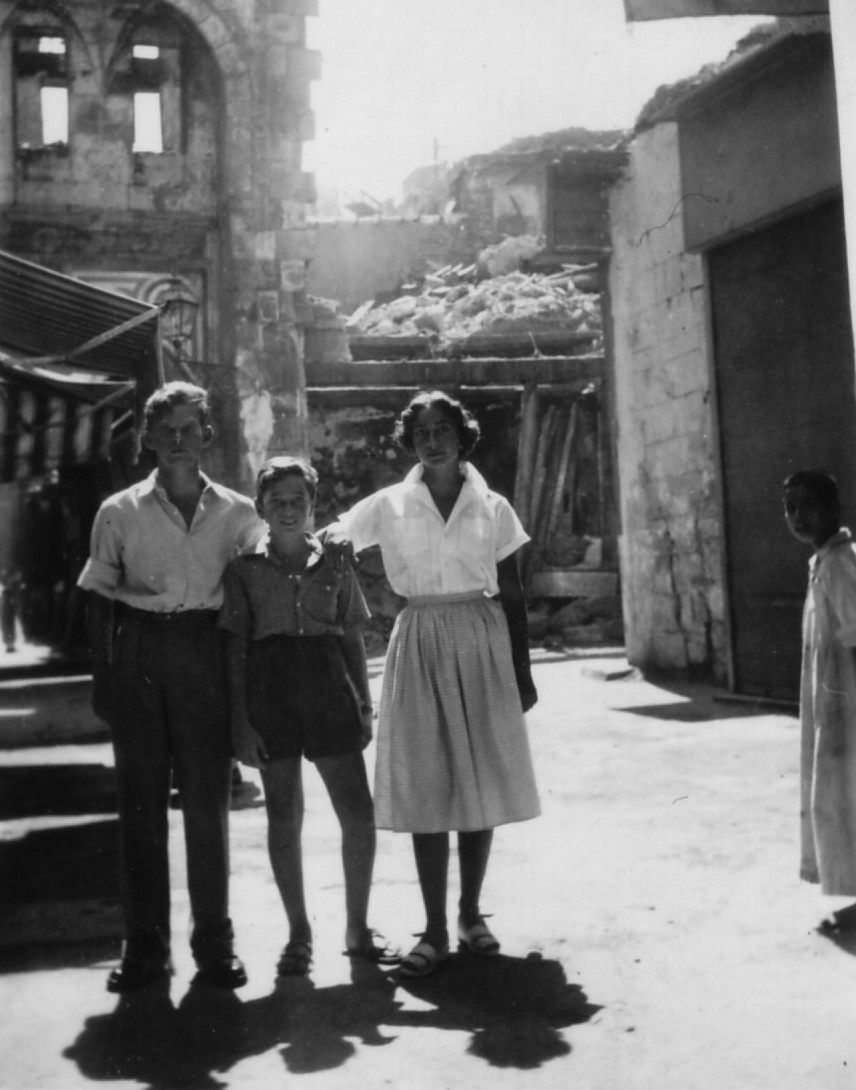

Born in Cairo, Egypt, in 1936, Claudia’s family came from a richly-woven tapestry of Sephardic cultures – her father’s side were from Aleppo in Syria, via Portugal and Italy; while her maternal grandmother’s family stemmed from Istanbul, Turkey.

She came over first with her brothers Ellis and Zaki to study art in London; but within just a handful of years, her parents Cesar and Nelly Douek followed because they were exiled by Nasser after the Suez Canal crisis of 1956.

Having been uprooted from all they had ever known, the Doueks were keen to make friends and invited their Jewish neighbours over for tea to their home in Woodstock Road, Golders Green.

“We made vine leaves, cheese filo pastries, hummus – all the things that we would have had for mezze (tea) in my childhood Egypt,” Claudia delights in telling me in her Hampstead Garden Suburb home.

But when the neighbours came in and saw the spread on the table, they were aghast.

“Are you sure you’re Jewish?” they asked, clearly expecting smoked salmon and chopped herring.

While taken aback at the time, it was Claudia who seemingly had the last laugh. Every dish her parents served at that tea was included as recipes in A Book of Middle Eastern Food, the bestselling seminal 1968 cookbook that launched her culinary writing career.

Moreover, the recipes later came to the attention of bosses at Marks & Spencer, who asked a Cypriot producer to turn them into their new mezze range. Those products – stuffed vine leaves and all – are still sold today in their thousands by the retailer.

So just how did British Jews go in just a few generations from turning their noses up at anything other than salted fish and pickled vegetables to becoming a community where falafel, shakshuka and shawarma are fully embraced?

Claudia’s first book – and indeed the success of those that followed, including Mediterranean Cookery (which was accompanied by a BBC series), The Book of Jewish Food and Arabesque: A Taste of Morocco, Turkey and Lebanon – certainly had their part to play in expanding people’s curiosity and culinary horizons, both in the UK and the wider diaspora.

But the answer to how Sephardi cuisine rose in prominence in the UK also perhaps lies in why she wrote the books in the first place.

Just like her parents, others who arrived in Britain as expelled Jews from the Arab world in the post-war years found themselves longing for the life that had once been theirs. A huge part of that was to recreate the dishes they had eaten at home, lovingly made by matriarchs over generations, then passing the recipes down verbally from mother to daughter.

Claudia, now 87, looks back fondly at her childhood in Cairo, where a vibrant melting pot of Ottoman and Mediterranean cultures lived side by side.

She recalls: “As with all Sephardi communities, entertaining and hospitality were the most important thing of our culture. We entertained a lot, for mezze, for dinners, for Jewish festivals.

“We had a cook called Awad and he lived in a hut on the roof terrace. My mother spoke to him in Arabic, but at home with us she always spoke in French.

“I recall we didn’t have a fridge or freezer, but instead an ice box, with ice coming every day in a large block to keep the meat and fish cool.

“Our mothers didn’t work, none of the women in my family worked. We had a large family – my father was one of ten, while my mother was one of six – and I had many aunts. While the cook prepared the meals, the women would be in the dining room making things like stuffed vine leaves and little pastries, the kind of thing that was labour intensive. They would sit around and chat and gossip. For me, that was my experience of ‘cooking’.

“I was given little tasks to do, like making balls of almonds or ka’ak (small crackers), for which I had to roll out the dough like a little snake, make into a ring and dip it in seeds, cumin or sesame before they were baked.”

Food, in many ways, reflected the hustle and bustle of old Cairo. “Our food was what you would call sensuous cuisine,” smiles Claudia. “It was full of fragrances, aromas and colour and plenty of herbs.”

Each family had their own way of cooking, influenced by whatever cultures had melded into the family genes.

She explains: “So diverse was the community, that the cuisine could vary not only from one country to another, but also from one city to another and even from one quarter of a city to another.”

Claudia’s immediate family mostly ate dishes of Syrian origin because of her paternal line, but one of her aunts made dishes stemming from Portugal and Livorno in Italy, where the family had also originally lived.

These included Claudia’s now famous orange and almond cake, a Portuguese speciality.

“We also had dishes like calsones, which we always ate on a Thursday and was a kind of ravioli with cheese emanating from northern Italy.”

When the community began to migrate over to Britain, Claudia came to realise that not only did many long for the foods they were used to eating, but there were also no cookbooks for anyone to learn from.

In Egypt, recipes were not written down, for fear another family might learn all their culinary secrets, Claudia explains. But sharing the recipes took on a new urgency once the community had relocated.

“My mother wanted to make the Syrian food my father’s mother had made for him back in Egypt, so finding those recipes became my first and primary mission.”

The more she spoke to the newly-migrated Jews, the more it became apparent that giving her the recipes was their way of helping preserve their culture.

“This was more than just giving me a recipe,” she reflects. “We really needed this book, so I did it for all of us.”

Some were sceptical that A Book of Middle Eastern Food would be popular with culinary-minded readers. In Israel, her publishers bluntly told Claudia that they did not expect to sell many copies.

“They said the food reminded them of Arabic culture and many had wanted to leave all that behind. But when the book came out, still it sold and it never stopped selling.”

Fifty years on, Claudia’s book has not only preserved a multitude of Sephardi recipes for generations, but has also proven to be a source of inspiration for other chefs around the world, including Yotam Ottolenghi.

As we near the end of this fascinating whirlwind tour of Jewish history and Sephardi cuisine, I come to bemoan the fact that as a mostly Ashkenazi Jew my culinary offerings are somewhat bland and unexciting in comparison.

Not so, argues Claudia, who reveals Ashkenazi food is actually far more interesting than many of us might know.

“Did you know fishballs are only in England? No other Jewish community has them,” exults Claudia. “And these actually come from the Portuguese method of deep-fried fish. Sponge cake and almond macaroons also have their roots in Portugal. Then we have challah, which is a special braided bread that originally came from medieval Germany.”

As Claudia speaks, her passion for food and where it originates is clearly discernible. She intends her next book to delve more deeply into the stories behind the people, who over the years have given her so many valuable recipes.

She’s also still discovering new regional dishes from the Middle East that have not yet been documented.

“The other day, I did a recipe of fish and beans with a yoghurt and tahina sauce, with pine nuts on top and also a little syrup dribbling sauce on top. Gosh, that was marvellous,” exults Claudia.

It’s safe to say the culinary maven, mother-of-three and grandmother still loves cooking for others.

“I adore cooking actually,” corrects Claudia. “I’m 87 and for me it’s my way of becoming absorbed in something that brings me pleasure and cooking for the people I love.

“As they say, what else do we have to give in life than good food?”

Thank you for helping to make Jewish News the leading source of news and opinion for the UK Jewish community. Today we're asking for your invaluable help to continue putting our community first in everything we do.

For as little as £5 a month you can help sustain the vital work we do in celebrating and standing up for Jewish life in Britain.

Jewish News holds our community together and keeps us connected. Like a synagogue, it’s where people turn to feel part of something bigger. It also proudly shows the rest of Britain the vibrancy and rich culture of modern Jewish life.

You can make a quick and easy one-off or monthly contribution of £5, £10, £20 or any other sum you’re comfortable with.

100% of your donation will help us continue celebrating our community, in all its dynamic diversity...

Engaging

Being a community platform means so much more than producing a newspaper and website. One of our proudest roles is media partnering with our invaluable charities to amplify the outstanding work they do to help us all.

Celebrating

There’s no shortage of oys in the world but Jewish News takes every opportunity to celebrate the joys too, through projects like Night of Heroes, 40 Under 40 and other compelling countdowns that make the community kvell with pride.

Pioneering

In the first collaboration between media outlets from different faiths, Jewish News worked with British Muslim TV and Church Times to produce a list of young activists leading the way on interfaith understanding.

Campaigning

Royal Mail issued a stamp honouring Holocaust hero Sir Nicholas Winton after a Jewish News campaign attracted more than 100,000 backers. Jewish Newsalso produces special editions of the paper highlighting pressing issues including mental health and Holocaust remembrance.

Easy access

In an age when news is readily accessible, Jewish News provides high-quality content free online and offline, removing any financial barriers to connecting people.

Voice of our community to wider society

The Jewish News team regularly appears on TV, radio and on the pages of the national press to comment on stories about the Jewish community. Easy access to the paper on the streets of London also means Jewish News provides an invaluable window into the community for the country at large.

We hope you agree all this is worth preserving.