Judge Rinder: ‘Who Do You Think You Are was a total gift to my family’

Television star discovers his grandfather Morris Malenicky lost seven relatives in the Holocaust

“There are innumerable privileges to being a so-called celebrity, but this was a total gift,” reflects television personality Judge Rinder, who delves into his family history for this week’s episode of Who Do You Think You Are?

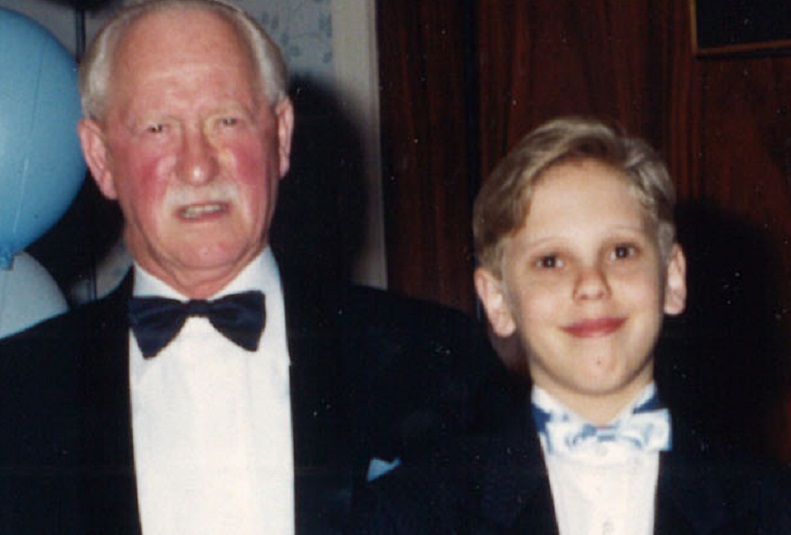

The 40-year-old star, whose full name is Robert Rinder, signed up to discover more about his maternal grandfather, Morris Malenicky and great-grandfather, Israel Medalyer.

At the heart of his story is his 94-year-old maternal grandmother, Lottie, described as “still very much at the quiet centre of our family”.

Get The Jewish News Daily Edition by email and never miss our top stories Free Sign Up

While her husband Morris was a Holocaust survivor, little is known about her father Israel, other than rumours he was “damaged in the war”.

Turning his attention first to Morris, Rinder tells me he knew his grandfather was the only one still alive after the war, while his parents, four sisters and brother were all killed at Treblinka.

However, Rinder knew very little about what Morris had actually experienced.

“When you are the grandson of a Holocaust survivor, it informs just about everything,” explains Rinder, whose mother Angela is chair of the 45 Aid Society.

“I’ve always been very interested and very aware, but like lots of grandchildren of survivors, they never tell their story in one coherent narrative.”

Travelling to his birthplace, in Piotrkow, Poland, Rinder is shown a collection of documents that finally cast light on his grandfather’s hidden past.

In an amazing series of coincidences, Rinder meets historian Netanel Yecheili, who tells him that not only did Morris’ family rent their apartment from his family, who owned the entire block, but their grandfathers were good friends as children.

Then, when he is presented with Morris’ birth certificate, Rinder notices the date is 11th February, the very same date as his visit and what would have been his grandfather’s 95th birthday.

“It was a complete surprise, genuinely unbelievable,” says Rinder. “To be sitting in the very place where he was born on his 95th birthday was incredible.”

He is also given a newspaper article detailing the names of Morris’ parents and siblings, which was written before the war. For Rinder, saying the names out loud for the first time was deeply poignant.

“We all know the significance of memory and saying the name of a person, but to be there in the place they had been and then to also get descriptions was very moving.

“The material described my great-grandfather as a little man who was always running about – well if you were to draft two lines about my grandfather, that would be him!

“It was proper human history. It breathed ruach into these people who had previously been nothing but a name. And before that, not even a name.”

While Morris’ family were taken off to Treblinka, he was sent into forced labour in a glass factory in Piotrkow, before going on to Buchenwald, Germany and then a sub-camp, Schlieben.

There he meets Sir Ben Helfgott, who knew Morris well and describes to Rinder for the first time how his grandfather physically looked when he arrived at the camp.

“I had absolutely no idea Ben was coming or that my grandfather was sent to Schlieben. I knew he had been in a camp, but I only knew it as Buchenwald.

“Sometimes stories would come out, often when you least expected them. For example, he would say, ‘never push yourself forward’ and then tell me about how he once pushed into a line where the work that people were conscripted into looked easier.

“But it turned out they were working with noxious chemicals. He was discovered and horribly beaten, but that was only the underlying luck of his survival, because while he was forced into harder work, it didn’t include working with these chemicals.”

Following the war, up to 1,000 Theresienstadt orphans were given the chance to go to the UK. The first group were taken to Lake Windermere and included Morris, who Rinder discovers, lied about his age to match the criteria for entry.

However, as a man who “adored this country and loved the rule of law”, Morris was troubled enough to set the record straight when he married Lottie a few years after arriving in the UK.

Turning his attention to Israel, Rinder reveals that his family had always thought he may have suffered from shell shock, having served in the First World War.

But he discovers that Israel served at home and never saw active service. His death certificate reveals however, that he died at Friern Barnet Hospital, a mental health facility.

As more information emerges, Rinder learns that his great-grandfather had probably suffered from what we now know as post-traumatic stress disorder, having been caught up in Russian military violence against revolutionaries during his childhood.

Discovering a close relative had mental health issues was “a genuine, dark shock to everybody”.

Rinder adds: “It was a secret that one might say was laced with shame. My grandma could never speak of it because it was considered such an appalling affliction.

“It’s made me want to be part of the conversation, to do what I can to help remove the stigma of mental illness.”

Reflecting over his experience, Rinder says he feels “more connected” to his grandmother, Lottie, and his wider family.

“The gift of this experience isn’t just mine. My mum and auntie grew up with a Holocaust survivor father with no context, no idea where he came from, where he lived, or what his family were like.

“To be able to tell them was extraordinary, and enormously important to them.”

Robert Rinder appears on Who Do You Think You Are?, Monday, 9pm, BBC One.

Listen to this week’s episode of The Jewish Views Podcast here:

Thank you for helping to make Jewish News the leading source of news and opinion for the UK Jewish community. Today we're asking for your invaluable help to continue putting our community first in everything we do.

For as little as £5 a month you can help sustain the vital work we do in celebrating and standing up for Jewish life in Britain.

Jewish News holds our community together and keeps us connected. Like a synagogue, it’s where people turn to feel part of something bigger. It also proudly shows the rest of Britain the vibrancy and rich culture of modern Jewish life.

You can make a quick and easy one-off or monthly contribution of £5, £10, £20 or any other sum you’re comfortable with.

100% of your donation will help us continue celebrating our community, in all its dynamic diversity...

Engaging

Being a community platform means so much more than producing a newspaper and website. One of our proudest roles is media partnering with our invaluable charities to amplify the outstanding work they do to help us all.

Celebrating

There’s no shortage of oys in the world but Jewish News takes every opportunity to celebrate the joys too, through projects like Night of Heroes, 40 Under 40 and other compelling countdowns that make the community kvell with pride.

Pioneering

In the first collaboration between media outlets from different faiths, Jewish News worked with British Muslim TV and Church Times to produce a list of young activists leading the way on interfaith understanding.

Campaigning

Royal Mail issued a stamp honouring Holocaust hero Sir Nicholas Winton after a Jewish News campaign attracted more than 100,000 backers. Jewish Newsalso produces special editions of the paper highlighting pressing issues including mental health and Holocaust remembrance.

Easy access

In an age when news is readily accessible, Jewish News provides high-quality content free online and offline, removing any financial barriers to connecting people.

Voice of our community to wider society

The Jewish News team regularly appears on TV, radio and on the pages of the national press to comment on stories about the Jewish community. Easy access to the paper on the streets of London also means Jewish News provides an invaluable window into the community for the country at large.

We hope you agree all this is worth preserving.

- Who do you think you are

- Judge Rinder

- Robert Rinder

- Sir Ben Helfgott

- theresienstadt

- The Boys

- 45 Aid Society

- Ben Helfgott

- Judge Robert Rinder

- Buchenwald

- Morris Malenicky

- Israel Medalyer

- Schlieben

- Piotrkow

- Kosher Culture

- interviews

- Celebrity

- Televison

- BBC One

- Friern Barnet Hospital

- Lake Windermere

- germany

- Poland

- Holocaust

- Nazi

- concentration camps

- Arts

- Features

-

By Laurent Vaughan - Senior Associate (Bishop & Sewell Solicitors)

-

By Laurent Vaughan - Senior Associate (Bishop & Sewell Solicitors)

-

By Laurent Vaughan - Senior Associate (Bishop & Sewell Solicitors)

-

By Laurent Vaughan - Senior Associate (Bishop & Sewell Solicitors)